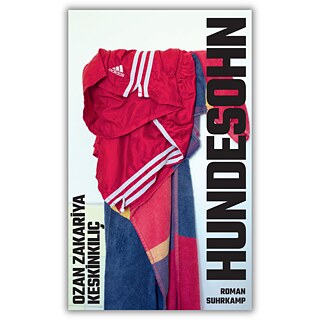

Ozan Zakariya Keskinkılıç has written a highly acclaimed debut novel, “Hundesohn”, which has won several awards. In this interview, he talks about how writing became a process of exploration, where faith and desire intersect, and why transformation sometimes has to be monstrous.

His language is as sensual as foreplay, as rhythmic as a poem, and as fragrant as sage and thyme. As a poet and scholar, Ozan Zakariya Keskinkılıç weaves poetic intensity with a precise gaze on Muslim-queer life worlds in Hundesohn. In the novel, Zeko moves between Friday prayers and Grindr dates while yearning for Hassan. But Hassan is not only his summer love from Adana, but also the eponymous Hundesohn, "son of a dog". That's why we first asked ...Ozan Zakariya Keskinkılıç: Who or what is a Hundesohn, a "son of a dog"?

It’s an insult rooted in Arabic, Ibn al-Kelb, and Turkish, Köpek oğlu köpek. At some point, the term slipped into German, carrying a distinctly negative charge. A “son of a dog” is dirty, insolent, and foolish—someone expected to obey and submit. He is cast out and punished.

In your novel, the protagonist Zeko reclaims the term.

Zeko associates dogs not only with violence but also with tenderness. I’m fascinated by that tension—the interplay between intimacy and brutality.

It borders on obsession, reminiscent of Kafka’s land surveyor K. and his futile pursuit of the Castle—who, incidentally, makes a cameo in Hundesohn. I’m drawn to borderlands and outsiders searching for belonging, for the fulfillment of immense desires. Hassan becomes Zeko’s projection screen—not only for sexual yearning but for the fantasy of becoming someone else.

That projection seems limitless. Is desire at its most intense when love is absent?

The moment desire is fulfilled, the tension that sustains it evaporates. Zeko does indulge his lust—he meets lovers, devours them, is physically present—yet remains absent, haunted by Hassan, comparing, calling out to him. Hassan’s unattainable presence becomes a constant undertow in the narrative.

Is Hassan as ideal as Zeko imagines?

Of course not—and Zeko senses that. Hassan is contradictory: dominant, distant, yet tender. Love and hate lie perilously close. That’s why the novel oscillates between luminous and painful memories.

Between Friday prayers and Grindr dates—what binds sex and faith for Zeko?

It’s not only a love story between Zeko and Hassan, but also between Zeko and God. Hassan is ever-present—but so is God. The longing for God mirrors the longing for beloved bodies. Both are forms of surrender.

There are countless ways to live faith and desire beyond normative frameworks,

Because Islam is often cast as the embodiment of homophobia. Queer Muslims live under double pressure—external and internal. They are forced to explain themselves, targeted from all sides with rejection, hatred, ignorance, and violence. That intersectional experience is brutal. Yet there are countless ways to live faith and desire beyond normative frameworks.

Zeko even enters a church, sits in the confessional. What does he seek there?

He toys with the expectation of disclosure. In confession, he has nothing to confess, lies, and ultimately confesses anyway. It’s a response to a secular culture obsessed with authenticity—Zeko resists that demand.

Still, Zeko isn’t free from normative pressure. How does he navigate adaptation and transformation?

Adaptation means mimicking a norm to survive. Transformation means slipping between states—refusing the lure of the ideal, perhaps even becoming monstrous. Transformation or metamorphosis offers the chance to break free.

What did you have to shed while writing this novel? And what metamorphosis did you undergo?

I wrote without knowing where it would lead. I relinquished control—that was the shock. With so many voices in my head, the challenge was to let the literary voice prevail. I used to write fearfully, managing risk. That has changed. Writing has become an act of exploration.

I’m writing a new poetry collection and my second novel. Right now, I’m immersed in mythologies—their images, their functions. I’m curious about kinships between figures, and how we invent new creatures that teach us about being human. I’ve been drawn to Şahmaran, akin to the Greek Medusa—half human, half serpent. Şahmaran has become an icon for Turkey’s queer movement. These crossings between human and animal continue to fascinate me.

In summer 2026, you’ll be a fellow at the Tarabya Cultural Academy. What do you envision for your time there?

I believe in an intimate relationship between text, space, and the body. In Istanbul, I’ll exchange ideas with other writers and read those who have written from and about the city. And, of course, I’ll leave the city now and then. Writing means moving between closeness and distance—transforming outward and inward. Let’s see what emerges.

Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2025, 219 S.

ISBN:978-3-518-43254-9

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.

November 2025