Journalist Henning Sußebach has written a moving book about his great-grandmother, who – against considerable odds – carved out her own path. The seemingly unremarkable life of this woman in the countryside offers a fascinating glimpse into the past.

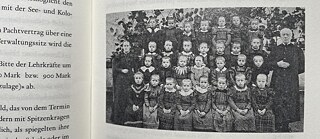

Spring 1887: In Cobbenrode, a village deep in the Sauerland, the new schoolmistress arrives. She is twenty-year-old Anna Kalthoff – the great-grandmother of ZEIT reporter Henning Sußebach. His book Anna oder: Was von einem Leben bleibt (Anna or: What Remains of a Life) is dedicated to her. At the outset, Sußebach reflects on death: every person dies twice – first biologically, then socially, when they are forgotten. “Ordinary people” like Anna Kalthoff are not commemorated with pyramids, mausoleums or monuments; no streets bear their names.At first, Sußebach knew almost nothing about his great-grandmother. He found only a handful of photographs and a few documents and objects that hinted at her story. No one in the family could reliably tell him about the ancestor who died in 1932. She seemed destined to vanish into oblivion. That spurred the ZEIT reporter’s determination to rescue her from this second, social death. He pored over parish registers, examined cadastral maps and researched in various archives and museums to reconstruct Anna Kalthoff’s life.

“Will I get a hump then?”

Anna was born in 1866 in a small village called Horn, about 65 kilometres from Cobbenrode. When she was twelve, her father died, leaving her mother with eight minor children. In the years that followed, Anna’s older sisters married, her brothers moved away – one even crossed the Atlantic at the age of 18, only to die years later in a Californian workers’ lodging: “A brother who will have sought happiness in America in vain. Sentences in the future tense, in the future perfect – the privilege of a descendant who leaps through epochs like a time traveller, forwards and backwards.”Anna was too young to marry, yet she realised her options were limited: becoming a maid, a servant, or a “spinster aunt” in her sisters’ households. The idea of becoming a teacher seemed relatively appealing, though in her childish imagination she supposedly asked: “Will I get a hump then?” This is one of the few family anecdotes about her. The anxious question had a serious undertone: “Schoolmistresses were often those left over on the marriage market – women who found no husband because they did not meet conventional standards of beauty.”

From Village Schoolmistress to Matriarch

Sußebach reconstructs Anna’s life piece by piece, and much that is astonishing comes to light: her forbidden love for Clemens Vogelheim, four years her junior, son of a merchant and “village prince”. Only twelve years later, after Clemens’ father’s death, would they marry. Anna could not remain a teacher, however, as the state forbade married women to practise the profession. Their marital happiness lasted only a few months before Clemens died in an accident. Thanks to her husband’s will – and against the Vogelheim family’s resistance – Anna became a matriarch: landlady, postmistress, wholesale trader and single mother to a son.Six years later, Anna surprised her family and the village again: she fell in love with Bernhard, a teacher nineteen years her junior, and married him. About a year later, their daughter Maria was born – the author’s grandmother. Together with the son from her first marriage, the four formed “an early patchwork family”, although at that time “fairy-tale terms” such as stepfather, stepson and stepsister were more commonly used

A Narrative Non-Fiction Book at Its Best

Sußebach skilfully fills the many gaps left by scant sources. He broadens the perspective by embedding Anna’s story in the historical context from the Prussian kingdom to the end of the Weimar Republic. He also offers thought-provoking conjectures about what certain situations might have been like, what Anna may have thought. These narrative elements make the “character” Anna vividly come alive.Sußebach has thus produced narrative non-fiction at its finest. He wraps history in stories and discovers in his great-grandmother a singular woman – “one like no other, and one like many”. Her life, he believes, is also prototypical. Anna became an emancipated, self-determined woman: “Whether Anna belongs in the history of the women’s movement as an early instigator or a later participant – hard to say.”

Finally, the book poses questions to us, the present-day readers, who so readily feel superior to those who came before and judge them lightly, sometimes harshly. Do we grasp that we too are merely “passing through”? Are we truly the “proper judges” of the past? Sußebach ends on a reflective note: “Time glides like the light bar of a photocopier across the generations: darkness, then briefly light, then darkness again. It happens quickly.”

Henning Sußebach: Anna oder: Was von einem Leben bleibt. Die Geschichte meiner Urgroßmutter.

München: C.H. Beck, 2025, 205 p.

ISBN: 978-3-406-83626-8

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.

München: C.H. Beck, 2025, 205 p.

ISBN: 978-3-406-83626-8

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.

January 2026