Der inoffizielle Botschafter in Berlin

Cartoons

Wem ist der Karikaturist Oliver Harrington ein Begriff, der eine zentrale Rolle in der deutsch-amerikanischen Geschichte spielte? Von der Harlem Renaissance bis zur Teilung Berlins, zeichnete er als Chronist der modernen Weltgeschichte diese Ereignisse in seinen meisterhaften Comics auf.

Diese Folge anhören: Apple Music | Spotify | Download

In dieser Folge porträtieren Sally McGrane und Axel Scheele den außergewöhnlichen, aus New York City stammenden, schwarzen Künstler Oliver „Ollie“ Harrington. Sally McGrane ist Journalistin und schreibt für „The New York Times“, „New Yorker Magazine“ und „Die Zeit“. Aus ihrer Feder stammt außerdem der Spionagethriller „Moscow at Midnight“. Axel Scheele ist Musiker und Podcast-Produzent. Unter anderem produziert er den deutschsprachigen Kinderpodcast „Ollarikchen“. Mehr über seine Arbeit ist auf seiner Webseite zu erfahren. Sally und Axel leben mit ihrer gemeinsamen, deutsch-amerikanischen Familie in Berlin. Ihre Folge erzählt die Lebensgeschichte von Ollie Harrington, einem amerikanischen Karikaturisten, der die letzten drei Jahrzehnte seines Lebens in Ost-Berlin verbrachte. Die Musik zu dieser Folge stammt von Oscar Brown Jr. und wird mit der freundlichen Genehmigung von Africa P. Brown von Bootblack Publishing Company LLC verwendet. Das Titelbild zur Folge zeigt ein Porträt Olli Harringtons, gezeichnet vom deutschen Karikaturisten Harald Kretzschmar. Außer dieser Folge haben Sally McGrane und Axel Scheele die Episode „The Mom-and-Pop Store“ produziert.

Transkript

[MUSIC]

[LAUGHTER]

Dr. Walter O. Evans: Do you know Ollie Harrington?

Keith Knight: It is surprising how little Ollie Harrington is talked about here in the States.

[LAUGHTER]

James Sturm: When I discovered Harrington, I was really blown away by how such a brilliant cartoonist could be kind of relatively unknown.

[LAUGHTER]

Warren Bernard: I wish that more people knew about Ollie Harrington.

[LAUGHTER]

Dr. Kay Clopton: He wanted the world to see what was going on. He wanted the world to see African Americans as the people they were and are.

[LAUGHTER]

Dr. Richard Powell: He’s in a world that is full of incredible Black artists and intellectuals, and they set up shop in Paris.

Dr. Walter O. Evans : Ollie was extremely talented. He should be known. He’s one of the greatest cartoonists that’s ever lived.

[MUSIC]

Dr. Kay Clopton: I would say he brought his A game to everything he did. And so, you see his best in all of his work.

Jenny Robb: You know, so many things that we talk about, about the 20th century, he was right there. To have traveled to East Berlin for work and then to have the Wall go up while he was there is pretty extraordinary.

Wolfgang Koenig: He had this very characteristic style. Nobody was drawing cartoons, at least in the GDR, nobody was doing it like he did.

Helma Harrington: After the fall of the Wall, he practically didn’t work anymore. One would think you are freer to work and not so much restricted. But it doesn’t work like that, only in theory.

Keith Knight: You know, it’s laugh, laugh, laugh, punch in the face. And that’s what cartoons do.

[MUSIC]

Dr. Richard Powell: I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that Ollie Harrington — he’s an American master.

Dr. Walter O. Evans: His cartoons dealt with issues that Black folks deal with every day. So yeah, he was quite well known. Until he wasn’t.

Dr. Richard Powell: I just think that it’s a shame, though, because if anybody deserves an important, significant close look, he does. My name is Rick Powell. I’m a professor of art history and African American Studies at Duke University.

Keith Knight: We refuse to teach what has happened in our past. And so, we’re destined to repeat the same thing over and over again. And I think that’s really America’s Achilles’ heel. My name is Keith Knight, gentleman cartoonist. I’m the creator of three comic strips, and I’m also a co-creator of the streaming series “Woke.” What happens is you just realize that the stuff you’re writing about now, he was writing about almost 100 years ago.

[MUSIC]

Dr. Richard Powell: He was born in 1912.

Warren Bernard: In Valhalla, New York, which is in Westchester.

Dr. Richard Powell: He is the product of an African American father from North Carolina and a Hungarian-Jewish mother.

Warren Bernard: At the age of nine, he moved down to the Bronx.

Dr. Richard Powell: And so, he’s a mixed-race kid growing up in the Bronx at the beginning of the 20th century. He’s in elementary school, and it’s a mixed-race school.

[MUSIC]

Oliver Harrington: In my 6th-grade class, there were only two Afro-American kids. Me and a strapping giant, Prince Anderson. One bright morning, our teacher, who was a Miss McCoy, ordered us, the perpetually grinning Prince and me, to the front of the class. Pausing for several seconds, she pointed her cheaply jeweled finger with what I think she considered a very dramatic gesture at the trash basket and said: Never, never forget. These two belong in that there trash basket. The white kids giggled rather hesitantly at first, and they fell out and peeled with laughter. For those kids, it must have been their first trip on the racist drug. I stumbled back with a shocked resentment, aware of the growing pain in my chest. Prince only grinned, but I realized that his eyes had noticeably narrowed. It was several days before I managed to pull myself together. Gradually, I felt an urge to draw little caricatures of this Miss McCoy in the margins of my notebook: Miss McCoy being rammed into our local butcher shop’s meat grinding apparatus. [LAUGHTER] Miss McCoy being run over by the speeding engines on the nearby New York Central Railroad tracks. [LAUGHTER] Well, one drawing, which I worked on all through arithmetic class, really grabbed me. It showed Miss McCoy disappearing between the jaws of a particularly mean tiger. I began to realize that each drawing lifted my spirits a little bit. And so, I thought, I can never let Miss McCoy see this. But I began to dream of becoming a cartoonist.

[MUSIC]

Dr. Richard Powell: And these were the beginnings of his coming into being a really, really fine cartoonist.

Warren Bernard: So, when he went to DeWitt Clinton High school, which was no slouch high school — Romare Bearden, the artist, and James Baldwin, the writer, both graduated from DeWitt Clinton. So, he got out of there in the teeth of the Depression in 1929. He moved to the YMCA in Harlem.

Dr. Richard Powell: On 135th St and as a young man, he’s going to the barber shops and hanging out with other African Americans, and he’s listening to jokes, and he’s listening to all the things that people say in a kind of a popular, jocular way, and he’s taking all of this in. And fortunately, he’s able to channel this through his connections to media, through newspapers, Black newspapers ...

Warren Bernard: ... That were there basically because of outright racism. My name is Warren Bernard. I am a comics historian and was a longtime cataloger at the Library of Congress. I’ve known about Ollie Harrington for a number of years, and it was through this first book called “Bootsie” that came out in 1957, I believe. Now, I thought it was eye-opening because I wasn’t aware that this kind of work was being done for a) the Black newspapers, then b) I knew nothing at that point that there even were Black newspapers and what the Black newspaper meant to the African American community during basically the entire 20th century. If you go and read histories of political cartooning in the United States, you don’t see anything about the Black newspapers. The Black newspapers were very interesting because they were basically self-contained financial, marketing, distribution, and sales units. They had to build their own printing plants. They had to have their own editors. They had their own writers, and of course, they had their own cartoonists.

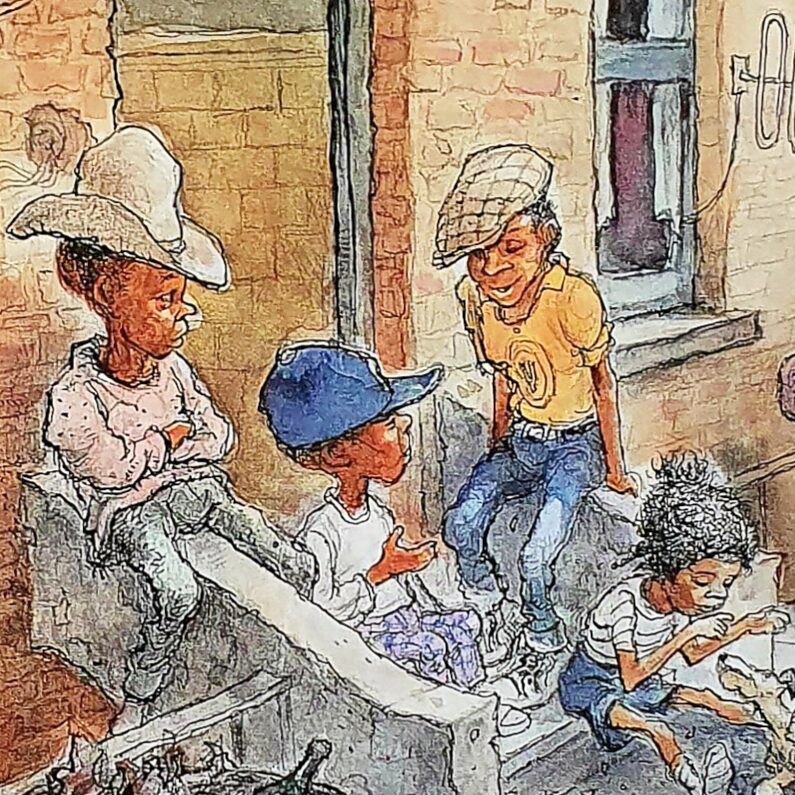

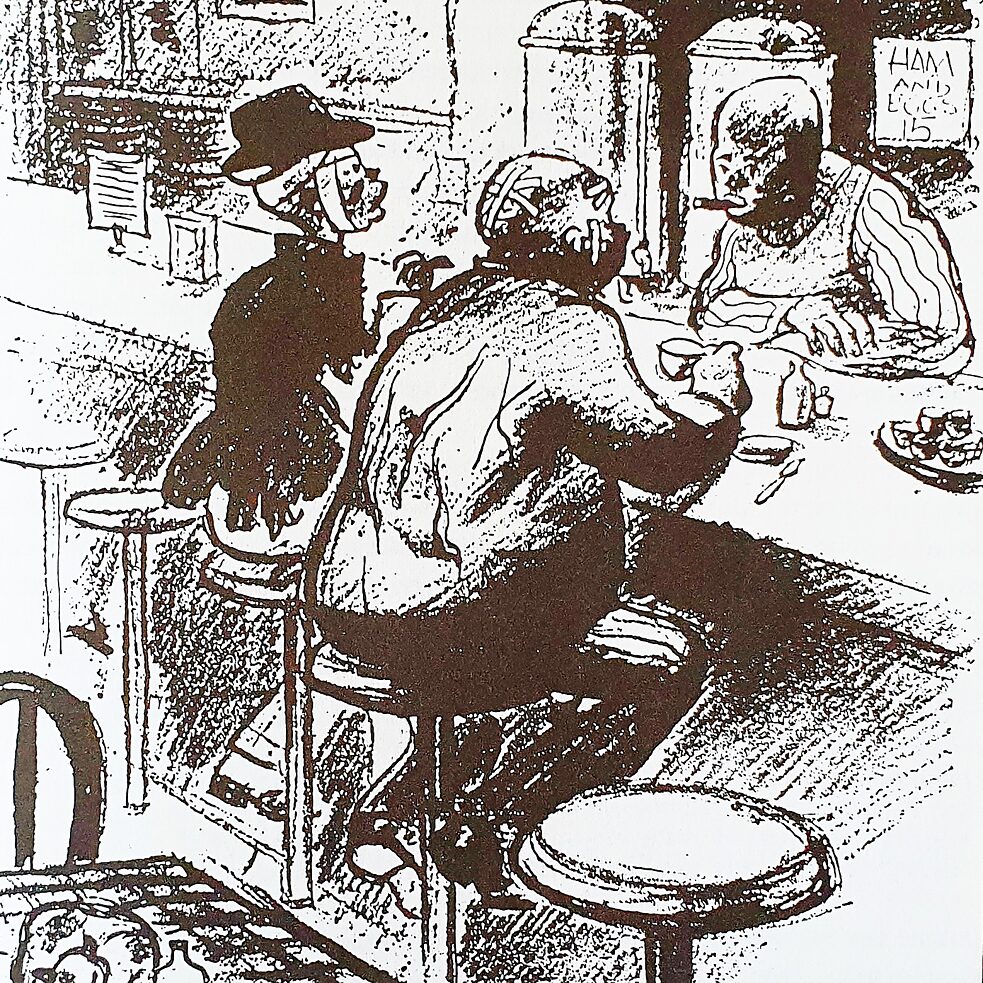

Dr. Richard Powell: And he works early on in his career with some really, really important publications like the “Amsterdam News,” which gives him an opportunity to do cartoons. And his cartoons are about Harlem.

[MUSIC]

Oliver Harrington: I met the most fantastic people who took a great paternal interest in me. Because there were great dangers too, which I wasn’t prepared for. I’d never had a drink on Brook Avenue. And so, it was someone like Langston Hughes who said: Well, look man, you don’t need this stuff if you don’t want it. Drink ginger ale. And it took me years before I began to pour a little gin into the ginger ale. But Langston Hughes and I because he was a fatherly figure to me, he was quite a good deal older, but such a wonderful and protective man. And through him, he explained some of his ideas, why people in the ghetto laugh so much. Why Prince Anderson in that school, for instance, grinned automatically all the time. He said: Well, it’s laughing to keep from crying, you know? And that’s what it is. Still is. But it creates a fantastic form of humor. Almost “mislike” humor and a sustaining humor. And I love it and have continued to love it.

[MUSIC]

Warren Bernard: And I think it was 1935. He started working with “The Pittsburgh Courier” and came up with a single-panel strip, “Dark Laughter.”

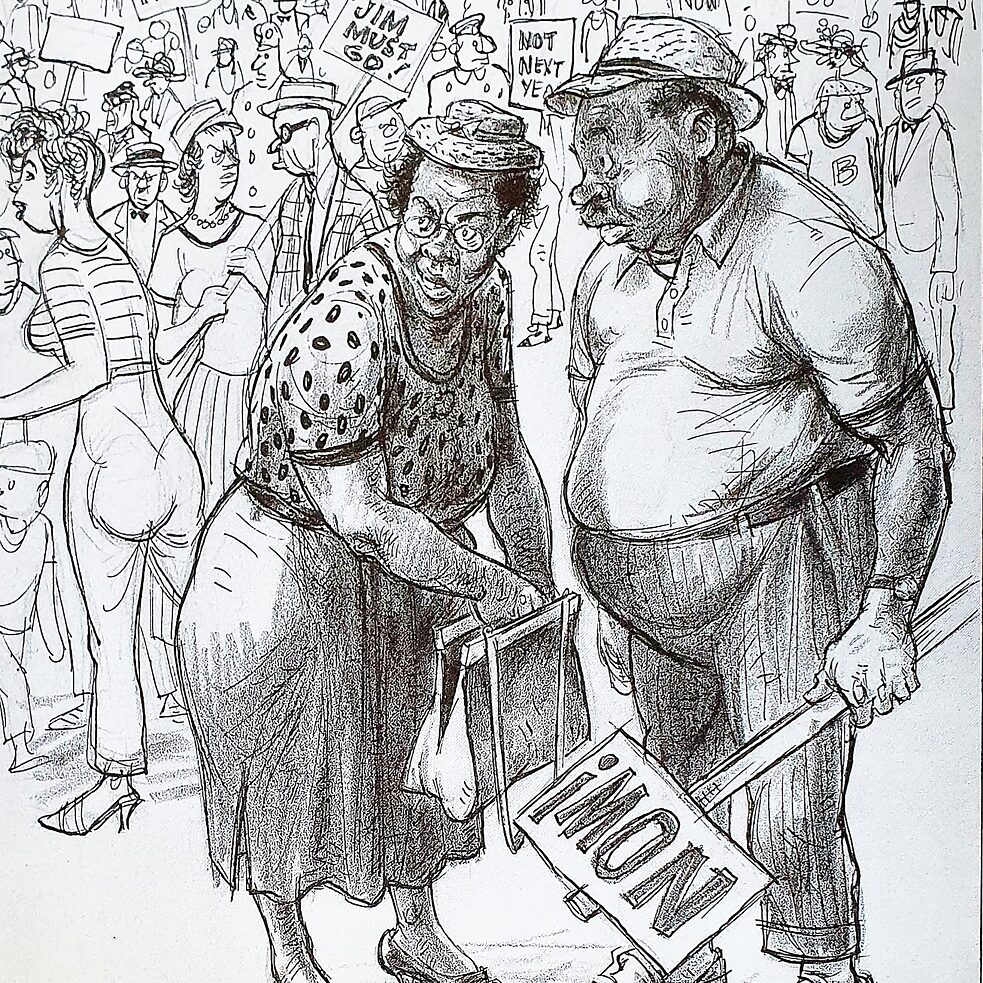

Dr. Richard Powell: Just think about the title: “Dark Laughter.” In other words, I’m dealing with this world of Harlem. This world of brown and beige and Black people. But I’m also looking at the humorous side of it, but lying within the humor is a political statement, is a social statement.

Dr. Kay Clopton: He also wanted the world to see that African Americans did have heart. They did have humor. They had lives. And they just wanted to live — that we want to live — in a society like everyone else. That we want to be able to have lives, where we’re happy, that we’re striving, we’re successful, that is not just misery, that we do have fun, and that we can smile and laugh in a world that seems to be constantly confronting all of us with darkness and peril. I’m Dr. Kay Clopton. I am the outgoing Mary P. Key Resident at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. I’m also co-curator on the “Dark Laughter Revisited, the Life and Times of Ollie Harrington” exhibit.

Warren Bernard: 1936, ’37 — somewhere in there — he went to the Yale School of Fine Arts.

Dr. Richard Powell: So, he graduates from Yale. He moves to Harlem, and he becomes a part of a really active scene in Harlem in the late ’30s, early 1940s.

Keith Knight: Me and my friends always used to say like, you know, white people always talking about how they wish they could go back in time, [LAUGHTER] and as Black people, we’re like, no, you know, I’ll go as far back in time as maybe 1989 or something. But the older I get, the more I sit there and go, man, I would have loved to have been around folks in the Harlem Renaissance. And what that must have been like to be at salons with all these amazing poets and writers and intellectuals and artists and stuff. So many people get mentioned in that period of time. But yeah, Ollie Harrington was there, and you just don’t hear much about a cartoonist being there.

Dr. Richard Powell: Shortly after that, he gets an opportunity to be a war correspondent, and in my mind, this is a really, really important moment because he decides to connect with the segregated troops. So, he’s hanging out with young Black men like him and realizes how powerful and poetic and ironic that situation is — of Black soldiers putting their lives on the line and not being able to realize those full democracies back home.

Warren Bernard: Going through the war, he does a comic strip, so you know, Jive Gray and his team of fighter pilots shooting down a bunch of Nazi planes that somehow find their way over the Deep South. Jive Gray gets shot down and gets found by a typical Southern farmer who basically says: Well, it looks like we’ve got a rope ready for you, there’s going to be a good lynching tonight.

[MUSIC]

Oliver Harrington: I finally moved to the eleventh floor of this YMCA, where the so-called veterans lived. One of those people was a man who used to come and sit in my room and talk about science. His name was Charlie Drew. He was a doctor in one of the foundations in New York City. He had been trained at McGill University in Canada, and he was obsessed with the wonders of nature. He was doing experimental work on developing blood plasma from whole blood, and he’d made fantastic advances. And apparently, Harlem didn’t know about them, and apparently, a lot of people in the States didn’t know about them. But Winston Churchill knew about them. And Winston Churchill sent him, sent the embassy, instructions, and they telephoned the eleventh floor of the Harlem YMCA, and asked Charlie Drew to come to the embassy. These are stories you will never have heard. Charlie Drew went there, and he was received by the ambassador. I must admit that, in the beginning, Charlie was very skeptical about it. I was a great practical joker, and Charlie came to my room, he says: Goddamn it, Ollie! I know you sent that telegram. I said: Charlie, I really have nothing to do with that, but there’s only one way to prove it. Call the British Embassy. And he gave me a skeptical look, but he called the British Embassy. And they said: Dr. Drew, please come, we’re waiting for you. Charlie Drew went there, and they told him: We have a great problem. We’re trying to save the people from Dunkirk. With your method, perhaps we can. Charlie was on a plane for London. Later, Charlie was called the “Angel of Dunkirk.” After a while he returned to the United States, his draft board told him that he should go to the Navy recruiting officer. He was sent to Washington, where he was interviewed. They knew the name. They received him with what they had hoped would be open arms. When he appeared they said: Dr. Drew, we’re afraid that a terrible error has been made. Go back to your draft board. Charlie went back to the draft board so embittered he swore he would never speak to another white person.

[MUSIC]

Dr. Richard Powell: So, it’s during this time period that he becomes involved with the NAACP as their kind of public relations communications person, and he ends up getting involved with all of these incredible cases of Black vets who are attacked and beaten in the South for wearing their uniforms, for asserting their rights as American citizens. And he teams up with Orson Welles, of all people. Orson Welles has a radio program, I think on ABC.

Orson Welles: Good morning, this is Orson Welles speaking.

Dr. Richard Powell: And there’s one particular case that’s really, really horrible about a black man, Isaac Woodard, whose eyes are gouged out by the police in South Carolina.

Orson Welles: Well, ladies and gentlemen, when I left off worrying about this broadcast long enough for coffee at an all-night restaurant, I found myself joined at the table by a stranger. A nice, soft-spoken, well-meaning, well-mannered stranger, he was. He told me a joke. He thinks it’s a joke. I’m going to repeat it, but not for your amusement. I earnestly hope that nobody listening will laugh.

Dr. Richard Powell: And Ollie Harrington provides all of the information to Orson Welles, and nobody’s really talked about this at great length. But I really believe that Orson Welles picked up on the theatricality of Ollie Harrington. Orson Welles picked up on the drama of Ollie Harrington, and so, when he’s doing those reports on ABC News about Isaac Woodard, he’s really channeling the stories and the narratives that Ollie Harrington gave him.

Warren Bernard: And there was, I think it was a “New York Herald Tribune,” had a symposium on social justice. I think there was an incident down in North Carolina, where a town got burned, and he basically took the United States Attorney General to task on why, you know, you can find all these spies during World War II. Why couldn’t you find anybody who did this?

Dr. Richard Powell: And frankly, his politics and his activism scares, I think, a lot of the people of the NAACP, and they say, you know, you’re too tough. You’re too critical. You know, you’re not toeing the line enough. And all this involvement in leftist politics during this time period, he saw the writing on the wall. He knew that this was the moment of the Red Scare. He knew that because of his activism, he was going to be linked to the Communist Party.

Warren Bernard: And you need to have some context for this. So, back in the ’20s and ’30s after World War I, there was this big overlap between communist feelings and the quest for racial equality. It wasn’t unusual in intellectual circles for people to be attracted to the Communist Party, whether they were Black, or they were white.

Dr. Kay Clopton: We have a copy of this FBI file that they kept on him. There’s actually a lot of pages that are blacked out. You get a lot of pages to tell you that ”a trusted informant” told them that he was a Communist, but that would be the only part you could read. And then, the rest of it’s blacked out. One of my favorite pages is actually — we have no idea what happened, we know that they did an investigation — it was just two pages of just everything blacked out, and the last line, the only thing you can read is: Upon further inspection, there is nothing to this, and we have closed the case.

Victor Grossman: Somebody tipped Ollie off — if he values his health, he better see about getting away from the United States.

Dr. Richard Powell: So, miraculously in the early ’50s he applies for an opportunity to go abroad, and he leaves the United States and moves to Paris.

Keith Knight: James Baldwin and Chester Himes, they just talked about Ollie Harrington being like, the ladies’ man of their whole [LAUGHTER] community, and he was a great storyteller.

Dr. Richard Powell: And you know, people focus on Richard Wright, but the star of the party — and it was an ongoing party for several years in these cafés — was not Richard Wright. It was Ollie Harrington. Because Ollie Harrington was the raconteur. Ollie Harrington was the jokester.

Warren Bernard: He worked in Paris. He was approached by “The Daily Worker,” the United States’ “Daily Worker,” what little there was left, and he started to work for them from Paris.

Dr. Richard Powell: But all things come to an end because, at the end of the 1950s, Richard Wright surprisingly dies, and it’s kind of a mysterious death. No one really knows what happened. He was talking and fine, it seemed to be, one day, and within a week he was dead.

Warren Bernard: Harrington was convinced Wright was killed by a CIA plot. And oh, by the way, back then, at that time, given the circumstances, one could go ahead and say stuff like that and not be considered totally “Looney Tunes.”

Dr. Richard Powell: When Richard Wright dies, Ollie Harrington goes to Berlin for a meeting to talk about doing illustrations for some American books. And the Iron Curtain goes up. And so, he makes a new life for himself there.

Victor Grossman: Hello, this is Victor Grossman. I became a friend of Oliver Harrington because he asked if I were interested in working with him at Radio Berlin International.

Helma Harrington: We met in a restaurant. It was ’63.Dr. Richard Powell: And he’s working for a publication that, I guess is still in existence in Berlin, “Eulenspiegel.”

Wolfgang Koenig: “Eulenspiegel” was a weekly satirical magazine in East Germany, in the GDR. More or less everybody knew it, not everybody got it because, you know, the GDR was an economy where lots of things were lacking, and also paper. So, I think they could have sold twice as many copies as they did, had they had the paper to print enough. So, quite often his cartoons were on the front page or on the back page, so full-page size, and the people who read the magazine, not necessarily every week but now and then, would know him.

Victor Grossman: His cartoons were in “Eulenspiegel,” and it was always against American domination in Latin America and such subjects. Or also subjects like racism in the U.S.A.

Helma Harrington: He did cartoons here, you know. But he only got occupied by international themes. He didn’t tackle any GDR problems or interior politics. I guess he was careful.

Wolfgang Koenig: He did not like everything that was going on in the GDR, of course. Nobody did or almost nobody did. My name is Wolfgang Koenig, I’m a journalist. Ollie lived around the corner from me. And one time, I took my little son, he was about the same age as Ollie’s son — although Ollie was 30 years older than I was — and so, we became friends somehow, so we met from time to time. He made me aware of a person that became one of my favorite jazz singers because he had an album of this guy, and I could borrow it and tape it. It was an album by Oscar Brown Jr. Through Ollie, I got to know about him.

Victor Grossman: He sent a weekly caricature to “The Daily World.” Because he was an American citizen, he could travel easily to West Berlin, and he mailed them from West Berlin because that went much quicker. He was kind of happy that he had a nice new Renault. And he told this story: He was over in West Berlin, and he got stopped at a red light rather suddenly. The car in back of him couldn’t stop quite so suddenly and crashed into him. Not seriously, but enough that it was damaged. So, he got out, and the driver got out, and he expected to exchange information about their insurance, et cetera. The other guy wouldn’t give his information. By then, sort of a little crowd had gathered, it became a little unpleasant, so this guy gave him a telephone number to call, and he said he’ll clear it up. Well, I guess it was several weeks later that Ollie was in West Berlin again and called and made an appointment and met him at some little office, and they arranged the pay or whatever it was. What was the meaning of this? The guy was from the CIA!

Helma Harrington: He was being followed, you know. He was followed by Americans in West Berlin. I guess he was followed by somebody from here. Being watched from each side.

Dr. Richard Powell: And in Germany, he was the go-to person, like the Black ambassador in Berlin.

Helma Harrington: My husband liked to cook. He was a very good cook. We always had many people at our place. He could cook Chinese or Italian or American, whatever. Despite a relatively closed society, there came always people passing through Berlin.

Dr. Richard Powell: So, he lives a rather extraordinary life in East Berlin. But then, things change dramatically at the end of the 1980s with the collapse, so to speak, of the Wall.

Helma Harrington: After the fall of the Wall, you know, he practically didn’t work anymore, except those months in the United States.

Dr. Walter O. Evans: I tried to meet every artist that I collected. I tried to. And I even invited them to Detroit, and most of them came and spent a week or more at my home. I’m Walter O. Evans, I’m a collector of African American art, literature, books, manuscripts, documents, music, et cetera. And I’ve been retired now from the practice of medicine for 20 years. When he came to visit Detroit, he had not been here in a very, very, very long time, and he was not familiar with the changes that had occurred in the U.S. Now, we still have a long way to go, I mean, you look at the news every day now, and you see police brutality. In fact, I myself have been on the wrong end of police brutality on several occasions, and I don’t know how many times I’ve had to spread eagle against police cars for doing nothing, just being Black. A Black male at my age, and I’ll be 80 years old in another year and a few months. But we had made major advances, and he just was not aware of some of those advances, and I think he was still a little bit overly suspicious of the justice system. Which you need to be, but not as much as it was when he left the U.S.

[MUSIC]

Helma Harrington: When you’re older, you don’t have the time. That’s the way it is.

Wolfgang Koenig: After the end of the GDR, we somehow lost touch. And then also he died, not too many years after that.

Warren Bernard: He passed away in ’95.

Keith Knight: He just lived an amazing life. And that’s all you can ask for. As harrowing as it can be, that’s all you want to do.

Warren Bernard: And he passed away, and I don’t know if you’re aware of this or not, but in 2019, the Billy Ireland got a whole bunch of Harrington’s papers and originals and other archives from his widow.

Jenny Robb: I’m Jenny Robb, and I’m the head curator of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. So, we were really excited about exhibiting that, but we didn’t have quite enough for an entire exhibition. We ended up partnering with Dr. Walter Evans who is the largest collector of Ollie Harrington’s work.

Dr. Walter O. Evans: When I started collecting, you couldn’t go into a museum in this country and find anything by an African American of note. I mean, even if they had it, they didn’t display it. I started collecting art because I wanted my daughters to see artwork by African Americans, and they could not go to public museums in this country and see it.

Oliver Harrington: Ethnic mores ... Can we afford them? Do we know that they’ve got to go, or else? I think so, and I hope all of you think so. And this is the only reason I continue to do my cartoons. Oh, I’m getting a little bit shaky, and my hands aren’t quite in it now, but I’m going to get back to them. And I’m going to turn out the old same cartoons. And it’s for me and for you.

[MUSIC]