Sankt Nikolaus‘ finsterer Helfer

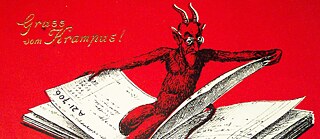

Krampus

Wenn es in den USA weihnachtet, dann beschenkt der Santa Claus die artigen Kinder, während den Unartigen in der Regel keine Konsequenzen drohen. In Europa begleitet der Knecht Ruprecht den Sankt Nikolaus. Dieser finstere Geselle, in manchen Regionen des deutschen Sprachraums auch Krampus genannt, droht unartigen Kindern mit der Rute. Wer genau ist eigentlich dieser Krampus und wo kommt er her?

Diese Folge anhören: Apple Music | Spotify | Download

Dieser Beitrag stammt aus der Feder von Erich Molinsky, Gastgeber von „Imaginary Worlds“, ein Podcast rund um Themen aus Science Fiction und Fantasy. In den einzelnen Folgen unterhält sich Eric mit anderen Kreativen über die Arbeit mit fiktiven Welten und er befragt Wissenschaftler*innen zur Beziehung von Fantasie und Wirklichkeit. Stephanie Billmann hat diese Folge als Produktionsassistenz betreut. Was ist an der furchterregenden Figur des Krampus so faszinierend? Entgeht hier am Ende den Kinder und Erwachsenen in Nordamerika ein äußerst ungewöhnliches Monster? Die Musik zu dieser Folge stammt von Blue Dot Seesions, Sono Sanctus und Arthur Benson.

Transkript

Eric Molinsky: For THE BIG PONDER, I’m Eric Molinsky. I have a theory about the holidays. I’ve always thought that Halloween is like a national purging of all of our dark impulses or scary, inappropriate thoughts. And once that’s out of our system, and our minds are clear, we’re ready to welcome the pure wholesomeness and good cheer of the Christmas season. But that’s not exactly the way things work in Central Europe. There is a dark, devilish character who is a crucial part of the Christmas season. And his name is Krampus. You know how Santa Claus is supposed to check to see if you’re naughty or nice? Well in America, there’s no follow through on the naughty part. You don’t really get a lump of coal in your stocking. But in Germany or Austria, that job goes to Krampus, St. Nicholas’s partner. Krampus is the enforcer of the naughty list, and he comes on December 5th to punish the bad children. Jules Linner lives in Austria, and she says Krampus is so mainstream, you’ll see his hairy goat-like face and his long red tongue on dolls, toys — and, of course, chocolates.

Jules Linner: Oh yeah, 100 percent. So, around the time — like early November, early Christmas time ... So, like before the 6th of December, you always have chocolate St. Nicholases. And you also have chocolate Krampuses. And they look very frightening. It’s just like a small devil with like a rod and a bag and it’s like grinning. But you can buy gingerbread and chocolate figurines and all that kind of stuff.

Eric Molinsky: They look cute and delicious, but as a kid, Jules was scared of Krampus — even, St. Nicholas. Like in America where parents pretend to be Santa Claus, the adult members of her family would pretend to be Krampus and St. Nicholas for the kids.

Jules Linner: My dad had a staff of St. Nicholas that he would just carry outside the window, so we would see it. My grandfather used to rattle chains in the basement while that was going on to like symbolize Krampus. Us as 5-, 6-, 7-year-olds were incredibly frightened of the combination of the staff and the chains rattling because we were so scared of being taken away basically because Krampus also kidnaps bad people. So, he doesn’t just give them like coal or something, but he actually kidnaps them to beat them up.

Eric Molinsky: Or worse. I’ve read that Krampus drowns children, eats them, or just brings them to hell. Now, if you’re thinking, this seems kind of inappropriate for children — you’re not alone. I found an article from 1953 about an Austrian school administrator who was trying to get Krampus banned from kindergartens. He said quote, “There is too much fear in the world already: unemployment, high taxes —not to mention, the atom bomb. Let’s begin by throwing out Krampus.” Over the years, well-meaning teachers and psychologists have tried to make the same argument, but Krampus is more popular than ever. And Jules thinks the appeal of the character is psychological.

Jules Linner: I once wrote a paper on fairy tales. And that just comes to mind that how the evil stepmother is just your mother when she’s being cross with you. So when she’s angry at you — a child — it’s like, that’s not the same person as my mother. Kind of in the same way, like when you do something that is bad or like when you step out of line, there is this other person that will take over the punishment, but not the good, pure St. Nicholas.

Eric Molinsky: That’s so interesting. That’s true. ’Cause like as little kids, you know, your parents, you look up to them. You think they know everything. And then when you do something, and then your parent punishes you, and you see this side of them that’s really scary. It’s like, in a weird way, St. Nicholas and Krampus are those two different sides of your parent. It’s like really hard to reconcile when you’re a kid.

Jules Linner: Yeah. And it’s something I also witness in my day-to-day life. ’Cause I’m a teacher, and I teach with another colleague in the room, and I’m usually the bad cop, so I’m usually the one who’s fairly strict. And my colleague is like the more fun one. And then, the other day, my colleague turned into the very strict one, and the kids were like so overwhelmed by that sudden change. We’re used to having people in these roles. So, you’re the good one. You’re the strict one. And then when that switches, they just get very confused. Krampus and St. Nicholas have always like been presented as a duo. Like 5th of December is like the day of Krampus. And the 6th is the day of St. Nick. But they’re also kind of presented as friends. Like not as antagonists, but like they hang out together, and like they go from door to door together and like then do their duty. So, they’re not like working against each other. They’re just like, okay, bad kid, gonna kidnap that one. That one just gets candy.

Eric Molinsky: I began to wonder, are we missing out, those of us who live in a country that does not have a dark folklore figure associated with Christmas? Christina Albert thinks so. She grew up in Texas — still lives there. Her parents were German and Austrian, and they raised her and her sister in their traditions. So when she was a kid, on December 5th, she and her sister would put their boots outside the front door.

Christina Albert: The next day we would ... Well, I always had at least one piece of coal or one potato or one onion and then a lot of candy, but it was always the German candy, which you couldn’t get in the U.S.

Eric Molinsky: The lump of coal and potatoes were supposedly left by Krampus to symbolize the times that she had been naughty instead of nice. And the German candy — that had to be from St. Nicolo, as she called him.

Christina Albert: There’s no way, you know, because this is before Amazon, of course, and, you know, ordering things online like that ... And so, I thought I was special. I was the only one getting it, and it did make me behave better throughout the advent season.

Eric Molinsky: And leading up to December 5th, she would also get cards from Krampus — and those cards had warnings.

Christina Albert: And they were scary, but they would always be written on, and they would always have a reference to something I’d done. Like in the summer, right? Where I’d done something to my sister. And so, I believed this was real. And Santa? Okay, if you didn’t believe, you didn’t believe. But man, how could somebody know this about me? Something I did last over the summer, I believed for a long time. Until one day I looked at the card, and I recognized the handwriting. And I went screaming through the house that, Omi is Krampus! Omi is Krampus! That my grandmother was the devil, basically. Because I finally recognized it, and what was happening, of course, is that my grandmother in Vienna was sending boxes of stuff to my mom to do this.

Eric Molinsky: So, were you like genuinely scared of Krampus or was it like a fun scared or like a really scared?

Christina Albert: No, when I was little, it was really scary. As I got older, I was like, yeah, well I’ve been good, and he’s never done anything to me, so I’m okay. But he always knew something, right? So, I still was on my toes, but when I was very young, oh yeah. Scared to death because he was scary-looking. I thought he was real. I thought that he and Nicolo would talk and determine whether or not I deserve treats and whether or not I was good. And that sort of thing.

Eric Molinsky: So, tell me about what you do with your daughter with Krampus.

Christina Albert: Oh well when she was little, well we lived in the States. And then, I married a German chemist, and we moved to Germany. So, she speaks fluent German, and she kind of got it both. And she was scared of Krampus. I mean, she would tuck herself in at night and had to sleep next to me, tucked in. She thought that Krampus was going to come get her, you know, and boil her heart.

Eric Molinsky: So, what’s it like — for a lot of parents when it comes to Santa Claus, there’s like, oh, I remember being a kid and now I can spread that magic to my children. You still get to do that with Santa, but what’s it like in reverse? Like, oh, this is so much fun. My daughter is worried that Krampus is going to boil her heart?

Christina Albert: I know, you know, I got a lot of grief from, you know, from the more modern parents that I was doing this, but I thought that it was a good way to instill, you know, what’s good, what’s right, are you telling the truth. So, I think that it taught her respect, to be helpful, to tell the truth, to be kind without me being a scary mom. I think that I instilled really good things in her that way. And so, we can sanitize everything in this world and make it all, you know, fluffy and cotton balls for all of our kids and put them in bubble wrap — or we can teach them reality, you know? These things transfer over to reality.

Eric Molinsky: By the way, I checked in with Christina’s daughter who is grown up now. And she confirmed that, as a kid, she really thought that Krampus was gonna eat her heart if she misbehaved. But she also said that having Krampus as a punishment figure helped her gain a strong moral compass in life. And even today, she is still a little scared of Krampus. Over the last few years, Krampus has become a little better known on this side of the Atlantic, partially because of a Hollywood horror movie called Krampus from 2015.

[KRAMPUS TRAILER: ST. NICHOLAS IS NOT COMING THIS YEAR, INSTEAD A MUCH DARKER ANCIENT SPIRIT. HIS NAME IS KRAMPUS.]

Eric Molinsky: Al Ridenour wrote a book about Krampus. And he started organizing Krampus parades in Los Angeles eight years ago. At one point, he was approached by the producers of the Krampus movie, and they invited him to a screening, thinking that he would help spread the world. But ...

Al Ridenour: I didn’t like the film, so that all kind of went south. Lord knows, the folklore — there was no folklore that resembled there. In fact, when they said, what did you think of the Krampus film, they sent me a message. I said I didn’t know there was a Krampus in it because it’s so different from anything that, you know, related to the tradition. It’s funny, I mean, and I no longer have to tell people what a Krampus is, thanks to the movie, except I have to tell them what a Krampus is. If they really care beyond the movie, what it might be.

Eric Molinsky: The only other time that I see Krampus come up in American culture is when comedy shows make fun of this foreign tradition. Like the actor Christoph Waltz who was on The Tonight Show, and he was explaining to Jimmy Fallon what a Krampus was.

Jimmy Fallon: And this is — I’m not making this up, you ready to see what Krampus looks like?

[AUDIENCE CHEERS AND LAUGHS]

Eric Molinsky: Jimmy took out a little Krampus doll. The head looked like a ram’s skull with a long red tongue hanging out.

Jimmy Fallon: Oh my God! I’m not joking! That’s Krampus!

Christoph Waltz: I’m not joking either.

Eric Molinsky: Or on Conan O’Brien.

Conan O’Brien: We got a call and he wanted to come here tonight to show us the new Krampus, please welcome the Krampus. Let’s get him in here!

[APPLAUSE]

Eric Molinsky: Where a guy dressed as Krampus comes out, saying he’s trying to improve his image.

Krampus: But look, I never said eating children is for everyone — until now.

Announcer: It’s time for Cooking with Krampus!

Eric Molinsky: But in researching this episode, it was fascinating for me to get into the mindset of what it’s like to live in a culture where Krampus isn’t just normal, he is a crucial part of the holiday season, and he plays an important role in people’s communities. Matthäus Rest is a social anthropologist in Austria, and he studied Krampus as a phenomenon. He lives in a small town outside of Salzburg, and he was telling me ...

Matthäus Rest: I was just thinking like, just a week ago, I was doing something outside, minding my own business. And I just suddenly hear the sound of the ‘rolls’ that all the Krampuses wear in our region.

Eric Molinsky: By rolls, he means the little bells on their costumes.

Matthäus Rest: The neighbor boys would just kind of trying on their gear. And it’s immediately puts me back in this alert feeling of just like being interested, not being frightened, but just being kind of highly alert. And people are kind of moving, the onlookers are moving inside houses. It’s also kind of very easy to just ask someone, can I sit in on the next troop that is there, people that normally you don’t even know them that well. And that, I think, I’ve always appreciated.

Eric Molinsky: So, what does a traditional Krampus costume look like? Again, here’s Al ...

Al Ridenour: The Krampus we think of is a furry creature. That’s humanoid with a sort of hideous face and at least two horns, animal horns, goat horns. And then, he wears on his waist a belt with like large cowbells. And in his hand, he carries some kind of a switch or a whip made of horsehair. The image I described evolved out of his natural habitat, which is Alpine farms that have sheep and goats on them. So, you have the animal hides and the animal horns and the bells that he wears are the livestock bells, the cow bells that were not being used during the year. During the winter, when with Krampus came round.

Eric Molinsky: Krampus also comes from a tradition called Folk Catholicism, where local customs were incorporated into Christian practice. And this is before Christmas, as we know it, came into being.

Al Ridenour: Christmas got domesticated only with the Victorians. Before that, Christmas was a rowdy time for adults, young adults. And it was time for ... People would costume for the whole period between Christmas and New Year’s and go out in the streets and drink and shoot off guns to welcome in the New Year.

Eric Molinsky: Matthäus says in medieval times, St. Nicholas did have dark companions, but none of them were exactly Krampus. Still, a lot of people today in Germany and Austria ...

Matthäus Rest: ... have this strong idea that this is a custom that has been practiced since time immemorial and often say this predates the advent of Christianity in the region. And of course, this is possible. It’s just, I would say, highly unlikely because there is no indication that this happened. And also, Krampus the word is a very late invention. We are still unsure where it comes from, but it’s even ... I would say to this day, old people in our valley and in many other regions that have these long traditions, don’t even use that word.

Eric Molinsky: The earliest evidence he can find of Krampus in German and Austrian culture comes from the late 16th century. Although Krampus didn’t become a widespread cultural phenomenon until the 19th century. There was a trend where old traditions were being revived or reimagined as a reaction against modernization. People wanted to get in touch with their ancient cultural roots, even if they sometimes romanticized what peasant life or peasant culture was actually like. And what really made Krampus take off were postcards. The postcards were brightly colored like Christmas cards, but you’ve got this devilish looking creature dragging away children in chains or baskets. Matthäus says the postcards were like a 19th-century version of meme.

Matthäus Rest: The postcard would then be, in a way, a similar invention as Instagram. So, people were suddenly allowed by the Austrian postal system to send small notes without an envelope, which was, apparently, something that before that was just considered outrageous.

Al Ridenour: Yeah, those postcards were huge.

Eric Molinsky: Again, Al Ridenour.

Al Ridenour: These postcards were circulating — not only in Germany and Austria, which is where the actual people dress up as the Krampus — but also further east in Bohemia and Hungary and the Czech, what’s now the Czech Republic. So, the idea of this creature spread way beyond where the actual in-person practice was occurring.

Eric Molinsky: Now when I look at these postcard images, I don’t know whether I’m imposing my modern ideas, but it seems to me that even back then, it was supposed to be ironically funny, like so dark, it was ridiculously funny. Is that how people saw it?

Al Ridenour: Yeah, you’re not ... I don’t think you are. I think people want to imagine that the audiences for these postcards were very different and old-fashioned and not like we are today, but I think that the Krampus for ... Some of the cards actually were designed for adults. Adults would send them to adults. It wasn’t ... the cards weren’t as much for children. In fact, they even have even had the sexy lady Krampus postcards that ...

Eric Molinsky: Like slutty Halloween Krampus?

Al Ridenour: Yeah, actually. Well, there’s a whole second round of them in the ’60s. And those look like they were like the cartoons out of the old Playboy magazines.

Eric Molinsky: In 2004, an American company published a book in English about Krampus. The book included the postcards, and that’s when Krampus went viral worldwide. The same thing happened with Krampus parades in Europe. They’d been happening for a long time, but what really made them take off was social media. In the last 15 years, the parades have gotten more elaborate, each one trying to outdo the other. In fact, the parades seem to have become the dominant cultural expression of Krampus culture in Europe.

[CLIP: AUDIO FROM GERMAN KRAMPUS PARADE]

Eric Molinsky: I’ve seen videos of parades at night with dozens of people marching through the town wearing full-body Krampus costumes with giant horns, monstrous faces, and shaggy costumes. Sometimes, they’re led by a very stern-looking St. Nicholas, as if the Krampuses were his minions. And the Krampuses are doing synchronized dances with cowbells. Sometimes, there are special effects like dry ice or pyrotechnics. I saw one Krampus dragging a fiery ball on a chain. Another one had fire blasting out of his horns. But Al says, there are family-friendly events as well. Sometimes, small troops will go from house to house dressed as St. Nicholas and Krampus to give out treats or just a fun little scare. And years ago, he was in Germany, and he was watching a Krampus parade during the daytime. A lot of parents brought their kids.

Al Ridenour: And then, it also gives the kids a chance to, you know, show that they can be brave. And I witnessed that firsthand with the kids. You know, I’ve been at a Krampus Run, where I see the kid, a kid near me was like visibly trembling to the point that everybody nearby could actually see that he was trembling. And people, I felt like he was attracting attention. As the Krampuses drew close, people are kind of watching to see what would happen. And then, the Krampuses kind of do that thing you do when you come up to make yourself small like if you’re approaching a dog you don’t want to have a confrontation with. So, they kind of ... their posture becomes a little less aggressive, and they kind of reach out, and the kid actually steps forward. The parents give him a little push from behind, and he puts his hand out, and he shakes the hand, and then the kid, he just like bursts out in this huge smile. And everybody, everyone was watching that. And it just ... that was a moment that stayed with me kind of illustrating for me what, you know, how the kind of pride that it kind of can instill in kids. That, you know, you confront this thing, it’s a little scary, and it’s all in the made up, in the make-believe world, but it’s good rehearsal for later in life.

Eric Molinsky: When Al and his group started the Krampus parades in Los Angeles, they had a similar feel. They even staged them at a outdoor German-themed mall called Alpine Village in Los Angeles. But they also had an event for grown-ups called The Krampus Ball.

Al Ridenour: We had sort of themed acts. We had a ... there was a band called Krampstein, they played in Krampus costumes and they also, even the lyrics were reworked in German to reflect Krampus themes, so they were always our headliner. And then, we’d also have the Krampuses burst out and circulate through the crowd at one point around midnight and swat people — people compete to be swatted

Eric Molinsky: To be swatted, you said?

Al Ridenour: Well, with the switches the Krampuses carry, yes. You know, in the Krampus Runs and the things that are aren’t geared towards little kids, they’re, you know, the Krampuses will swat people that clearly want to be a lot of times. Like I said, people would compete. They sort of run up and sort of taunt the Krampus, and then, they would get hit. You know, the people that perform as Krampus, they’re always on the lookout to see, you know, what, sort of suss out how receptive the person will be to engaging. There’s sort of subtle rules of engagement to all this, and there’s a whole other tradition that says that these beatings that the Krampus gives that I’m calling them beatings. It’s such an overstatement, but the symbolic swat is supposed to bring you good luck. Yeah, being hit isn’t always a bad thing.

Eric Molinsky: No, actually sounds a little bit S&M to me, to be honest.

Al Ridenour: That’s been observed over here, too.

Eric Molinsky: So, when you put on a Krampus costume, and you’re at a festival — what do you feel? What does it feel like to put one on?

Al Ridenour: It’s fun because, you know, you’re given permission to be transgressive, and you can grab at people and swat people and scare people and chase people. And yet, it’s definitely liberating.

Eric Molinsky: Culture can flow in both directions. Some people in Europe have complained that Krampus is being too influenced by American culture. Some of the new Krampus masks in Europe have red LED lights in the eyes, which look cool, but it’s not traditional.

Al Ridenour: Well actually, they actually call them ‘Hollywood masks’ in German.

Eric Molinsky: But Matthäus says they’re still popular.

Matthäus Rest: The vast majority of the masks of Krampus today are much more inspired by horror movies and the whole fantasy genre. So, starting from orcs, very strongly in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Ring films, but also werewolves and witches and other forms of fantasy horror creatures.

Eric Molinsky: ... which has led to a resurgence of more traditional masks. A lot of them are made from wood, but some will have plastic pieces or latex or leather. Local craftspeople will work on them for months. And different regions have their own traditions for Krampus masks.

Al Ridenour: Some places have Krampus masks that the face actually opens up in the front, some have like flapping jaws. And some don’t even have horns, so it’s all very regional, and it’s all like this is how our parents did it, and this is how, you know, maybe our grandparents did it.

Matthäus Rest: For example, the Gastein Valley in the county of Salzburg in rural Austria — here, the masks are very heavy. They’re made from wood. They have often, normally they have six to ten horns, always in pairs. The horns are heavy, but also the woodwork is not very delicate. They’re, in a way, kind of grotesque masks, kind of caricatures, so the faces and the expressions, they often have. They have warts. They look like they’ve spent some time in this world or in another.

Eric Molinsky: Whatever material they’re made from, part of the appeal is losing yourself in the character. You become Krampus. In fact, you’re part of a pack of Krampuses. And since it’s usually young men in the costumes, things can get rowdy, especially if there’s drinking involved. I heard stories of Krampus parades ending in bruises or broken limbs. And in recent years, there’s been a lot of discussion around Krampus celebrations. How to keep them safe — and scary, in a fun way. Although Matthäus says even those moments when people act out can have an important function, especially in smaller towns.

Matthäus Rest: And of course, the Christmas season is extremely important for these mountain communities. This is when kind of the community as a whole earns a quarter or half of the revenue of the whole year. So, everything has to be perfect then. And so, in a way, it seems also that the Krampus is a very important time before that whole craziness of the tourism season starts, where people can actually be themselves and blow off some steam.

Eric Molinsky: In 2020 and 2021, Krampus events were cancelled because of lockdowns, which is too bad because if there was ever a time when people needed to sort of exorcise their inner demons — on a benign level — this would be it. Personally, what I like about Krampus is more theoretical and doesn’t need any parades. I’m just glad he exists as an idea that Christmas should have a balance between dark and light. Because for some people, Christmas is not the happiest time of the year. And yet, we’re surrounded by these messages that can make you feel like if your life is not a holiday TV special, there’s something wrong with you. So, I like to imagine Krampus as the black sheep of the Christmas family. The moment he shows up at the holiday party, he makes people nervous, which is why you like him. He rolls his eyes at the relatives you can’t stand, he spikes the eggnog, and he pulls you aside and tells you inappropriately hilarious stories. He helps you get through the darkness of the winter season, so you have the strength to keep going into a new year. I’m Eric Molinsky and you have been listening to THE BIG PONDER. This episode was produced by me and Stephanie Billman. The episode originally aired on the podcast Imaginary Worlds. If you’d like to learn more about Imaginary Worlds, you can subscribe wherever you get your podcasts or go to our website imaginary worlds podcast dot org.