Heritage The Amazon in the basements of the “palaces of the dead”

The reviewing of Brazilian collections in German museums is an opportunity to debate scientific racism, which largely structured the knowledge and the imaginary of the West regarding the forests and its peoples.

“I think the backyard where we used to play is bigger than the city. We only find that out after we grow up. We learn that the size of things must be measured by how close we are with them. In that regard, it should be like love”, wrote poet Manoel de Barros (1916–2014) in Memórias Inventadas: a Infância (Invented Memories: Childhood). For those who grew up having the world’s largest tropical forest as their “backyard”, climbing trees for fun is just as common as it is nourishing. In the immense diversity of the forest, there’s a special palm tree, a favorite among the Amazonian children: the açaí palm.“Açaí” comes from the Tupi language (yá-çai) and it means “crying fruit”. What seems to be a simple personification is actually a key concept in the “cosmovision” of these indigenous peoples: “My grandpa says that, in the past, every bird, game, tree and palm was a person like us, from another generation. That is why we respect nature”, said Celino Forte, who is very knowledgeable about the Karipuna people, in the state of Amapá, and one of the inspirations for the publication of Uasei, o Livro do Açaí – Saberes do Povo Karipuna (Uasei, the Açaí Book – Knowledge of the Karipuna People). The forest is, therefore, a “family member”, in the words of indigenous archaeologist Carlos Augusto da Silva, affectionately nicknamed “Tijolo” (meaning brick).

Biome mapping

For millennia, indigenous populations have known açaí, a species of palm, in the production of the delicious “açaí wine”. The species became known in Europe in 1824, when German botanist Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794-1868) scientifically described it in Historia Naturalis Palmarum: opus tripartitum (Natural History of Palms: a work in three volumes), and named the açaí palm euterpe oleracea Martius (In reference to Euterpe, the muse of Greek mythology associated with music, whose name means ‘the giver of pleasures,’ and oleracea, a botanical term in Latin indicating an edible species).Von Martius did more than creating the modern classification of palms; he also mapped Brazil’s biomes and produced the monumental Flora brasiliensis, cataloguing 22,767 species, nearly half of every plant currently known to science in Brazilian territory (the world’s largest plant diversity, with about 46,097 species, 43% of which are endemic).

Von Martius not only created the modern classification of palm trees but was also responsible for mapping the Brazilian biomes and producing the monumental Flora brasiliensis, cataloguing 22,767 species. This represents almost half of all plant species known to science in Brazilian territory to date (the world’s largest plant diversity, with about 46,097 species, 43% of which are endemic).

The appropriation of knowledge

Throughout his life, Von Martius catalogued what he had collected in just three years – between 1817 and 1820 – alongside a fellow Bavarian: German naturalist Johann Baptist von Spix (1781-1826). After crossing over 10 thousand kilometers and visited the then captaincies of the states of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Bahia, Piauí, Maranhão and Grão-Pará, the foreigners left Belem in Pará and returned to Europe carrying a vast quantity of material.This impressive achievement was only made possible by the appropriation of the knowledge and work of the indigenous people, who had been managing the territory for millennia, as well as the work of enslaved Africans and their descendants. In other words, the outsiders would never have been able to survive the journey and collect everything they did without the ancestral knowledge and the “cosmovision” of the people who live in the forest.

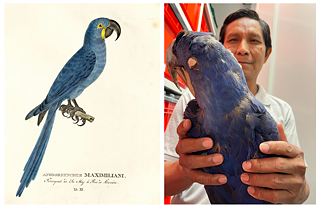

Martius and Spix brought to Europe field journals, diamonds from Minas Gerais, species of flora and fauna, as well as what they called “living pieces”, which were plants, animals and four indigenous people: three Miranha and one Juri. Only two out of the four people they kidnapped survived the trip, and were named “Isabela Miranha” and “Johannes Juri”. Both passed away less than a year after arriving in Munich. Their bodies, like everything else the Bavarian naturalists had taken, remain in European soil to this day.

Collections spread across different locations

In 2014, João Paulo Lima Barreto (Tukano), an anthropologist and professor at the Federal University of Amazonas, wrote the text Palácio dos Mortos (Palace of the Dead), in which he notes that “the objects taken by the Europeans, especially the diadems, are like deceased people. That house they call a museum, where they keep the bahsa busa (diadems) and other indigenous artifacts, is a house of the dead. The museum is a palace of the dead”.In August 2024, during the residency of the Cosmopercepções da Floresta (Cosmoperceptions of the Forest) project, in Munich, a series of objects that were separate, fragmented, in accordance with the rules of Western science, were observed in German museums. They were scattered across different locations: at the Five Continents Museum, in the Botany Collection at the Herbarium MSB Museum, at the Bavarian Zoology Collection. “I felt as if watching a dismembered body, with parts stored in different places”, said Barreto.

Historical reparations

A pertinent proposition would be providing exchange programs between museums and indigenous experts, aiming to rebuild knowledge and artifacts, as well as helping rebuild possible “repatriation” models, even if through 3D photos. “This would allow the specialists to resume their roles as guardians of knowledge, revitalizing their traditions in their lands and villages. Museums can play a vital role in reconstructing the histories and knowledge of indigenous peoples, connecting the past to the present and sharing this legacy with the world,” suggests Barreto.The reviewing of Brazilian collections in German museums creates a valuable opportunity for the discussion of racism and epistemicide, which structured most of the Western knowledge and imaginary of the forests and its peoples. It's an important debate that, in the future, can generate cooperation between scientific and cultural institutions that support indigenous peoples in safeguarding their intangible and territorial heritage, structuring actions for the conservation of the Amazon and the Atlantic Forest (such as plans to manage biodiversity in their territories based on their own cosmovisions and management technologies).

Ancestral and collective intelligence

The closeness of indigenous peoples with this “forest relative” – using the concept developed by Silva (Tijolo) – is an ancestral and collective intelligence, which resulted in the preservation of one of the world’s most diverse ecosystems. Studies have proven that 60% of the Amazon is anthropogenic, which means it results from the indigenous management of the forest, the land, the rivers and the cosmos for 12 thousand years. Such management, as Barreto explains, is part of a complex mediation, namely the “cosmopolitics” of the forest, wherein each person (and each collective) is connected with other beings and with the territory.Within this “cosmoperception”, the body “is a microcosm, because it synthesizes everything that exists in the terrestrial world; that is, the body is an extension of everything that exists, and everything that exists is an extension of the body. To science, the body is merely biological, but not to indigenous peoples. To us, the body is the synthesis of all these elements that surround us. Therefore, any imbalance caused in this relationship with the surroundings will be felt by the body”, summarizes Barreto.

It is necessary that, from the basements of the “palace of the dead”, this memory is awakened to the world: it is essential that we listen to those who intimately know, live and fight for the forest and its territories. In order for that to happen, museums and governments in Brazil and Germany need to create effective strategies of systematic cooperation with indigenous, riverside and quilombola peoples, so as to guarantee a future for those who are playing on açaí trees today.