Aris Fioretos The Seat of Longing

What happens when we map Europe not by borders but by longings? In his essay, Aris Fioretos explores two eccentric refuges – between Neuschwanstein Castle and Villa Natur, between fantasy and reality. A story about belonging, isolation, and architecture as a headquarters of desire.

At twenty past ten on the evening of the sixth of April 2002, a streak of light appeared in the south-German skies. An explosion followed seconds later, and blazing fragments plummeted to the ground. The meteor that had entered Earth’s atmosphere at an angle of 49° to the horizontal was the first in the country’s history – and the fourth in the world – to be observed irl.

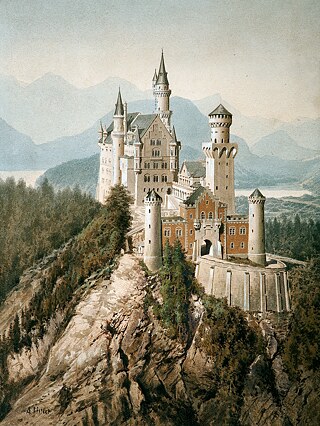

Drawing of the Neuschwanstein meteorite, 2002 | R. and N. Schmidts

European Fireball Network estimated that the space rock must have originally weighed around three hundred kilograms and been travelling at a speed of thirty kilometres per second. Upon entering Earth’s atmosphere it quickly lost velocity due to air resistance. Residents from Garmisch-Partenkirchen in the east to Allgäu in the west would later report a »bomb-like explosion«, »rolling thunder« and »rattling windows«. The presumed trajectories of the fragments were plotted from stations in Augsburg, Germany; Přimda, Czechia; and Austria’s Weyregg am Attersee, among others. The landing area could thus be triangulated with precision. Over the following months, amateur astronomers drew three crosses on their maps. The same number of fragments were found, with a combined weight of 6.215 kilograms.

The meteorite that for those six seconds had flashed across the firmament was named after the castle within the impact site to which I am travelling one icy April morning.

Neuschwanstein.

When those fragments fell to Earth some twenty-two years prior I had just started collecting materials for a book that would never come to be. Report from Mars was its working title. Through an array of text types (prose poems, entries from fictitious reference works, sociopathological case studies, adventures) it would paint a prismatic portrait of a boy’s upbringing in the Nordic welfare state to which his parents – a medical student and textile artist – had migrated in the fifties from Southern and Central Europe respectively. One of my (not least important) aims had been to show how people of mixed backgrounds learn the art of making themselves necessary in a foreign land. Or, to borrow Per Olov Enquist’s words from his essay about his failed novel project: for the child’s parents the question is one of »training in Swedishness«, while for their son it is rather »problems of belonging«.

Over the course of this project, however, the material changed. One of the stories, under the guise of an encyclopaedia article, was about a young Greek who, one March morning in 1966, enters a hospital waiting room in the nearby garrison town where the boy’s father has worked as a surgeon for some years. The more I wrote about this unemployed athlete, one who appeared to hail from a bygone era of human history, the more he revealed himself to me. Seven years later, Giannis Georgiades, as he would come to be called, was the protagonist of his own novel. The rest of the material, sprawling and abortive, was swept aside.

One of the unfinished texts was entitled »Villa Naturen«. Its focal point was an eccentric who lived in the countryside outside Kristianstad in southern Sweden’s Skåne County, the same area in which my family had lived for some years. The real inspiration for »Mög Janne« as I dubbed him had already passed away by the time I first heard mention of his name. Better known as »Möga-Jeppa« (»Grub Jeppa«) Olsson, he was born in 1877 in Degeberga, a town in north-eastern Skåne. A lifelong bachelor, devout Christian and royalist, he died in 1960 in Lund. But the reason for his fame was still standing in 1968, when I started year four in school in the nearby village of Österslöv.

Jeppa Olsson in front of Villa Naturen, postcard, 1949 | Photo: Sven-Gösta Johansson

Jeppa had first broken ground some thirty years prior, in the summer of 1938, compelled by terror at a looming war. He was employed as a caretaker by the army medic in Kristianstad, Andreas Bruzelius, in whose attic he lived. He had asthma and likely suffered from diabetes. Bruzelius, who at the time still owned a family estate in Österslöv, knew that the neighbouring farmer had a lakeside plot that was uncultivable, since the ground was waterlogged and the vegetation far too dense. On a visit to the site it was agreed that Jeppa would rent the plot for thirty Swedish kronor per year. From that day forth Jeppa would take the train to Österslöv as good as every day. He felled trees and drained the soil, initially with the help of Bruzelius’s son and one of the latter’s friends. By autumn a rudimentary dwelling was complete, but they had no time to lose: before the war reached Skåne they would need to build a shelter to house the most virtuous souls on Earth – the nurses who had tended to Jeppa at Kristianstad Hospital. Jeppa was convinced that with the Germans the end of the world was nigh.

With the completion of Österslöv’s new school in 1940 Jeppa’s plans expanded. He was given the leftover construction timber, which he was seen lugging down to the lake that entire summer. By this point the first dwelling boasted not only a kitchen with a paraffin stove, but also small chambers and a basic lavatory. Unlike the narrow beds, which Jeppa could move around as new rooms and floors were added, other large pieces of furniture donated to him by the locals were often installed before internal walls were fitted, which made them difficult to later rearrange. For company he had his Bible and the film stars on the walls. He surrounded himself with practical things such as axes, loose tobacco and spirits – not to mention all manner of junk that was waiting to be accorded a new purpose. Nutrition was no priority of his; eggs, herring and three-or-four-day-old bread sufficed. In the kitchen hung words of wisdom (among them Remember: life is short, death certain, eternity forever!) and a framed lithographic print of Oscar II. The lavatory was on the third floor, but an ingenious drain system meant that nature’s call could be heeded on the lower floors, too. The important thing was simply to reopen all the hatches, so that flow was unimpeded even from the top floor.

The staircase that a few years later would lead to the second structure – its highest point fifteen metres above ground level, crowned by a viewing platform that bore traits of both animal pen and ski jump – weaved its way through the building, past some twenty smaller rooms split across shifting floors, before returning down to the landing from which the visitor had taken their first step. The rooms bore names and borrowed histories alike. Beside the guest accommodation there was, for example, a »Blue Saloon« and »Green Bedchamber«, which was decorated with reproductions of famous artworks (kings, landscapes, the funeral procession of Charles XII). The »Tower Room« just beneath the stall on the roof offered a view of Balsberget hill on the other side of the lake, while the »Love Nest« was plastered with clippings and posters of stars of the day – Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable, and Swedish stars Greta Garbo and Edvard Persson… At ground level there was a pool (or »mud bath« according to some reports; its status was somewhat unclear), the water for which was pumped from the lake and heated by the sun shining on its tar-paper-clad walls. By the autumn of 1968 the cement had split amidst a sprawl of rusty pipes. Of the instruction signs that had been nailed to the trees, whose backwards letters often made their meaning difficult to decipher – not a trace.

Jeppa Olsson in his rowboat, 1949 | Photo: Sven-Gösta Johansson

While we played in Villa Naturen, its architect had lain dead eight years, having left the property years before still. Towards the mid-fifties – while an unmarried, still-childless foreign couple first embarked upon their »training in Swedishness« in Lund – he was committed to a care home in Kristianstad from which he was later transferred to Sankt Lars, the psychiatric hospital originally known as Lund Asylum. It is hard to believe that the creation that he left on the shores of Råbelövssjön lake, which for almost two decades had offered a different kind of sanctuary, would have been possible to realise even had Jeppa lived to be a century. Its unrealisability was its basic precondition.

When I study the images – most of those found in the archive were taken by Se photographer Sven-Gösta Johansson in the spring of 1949, a decade into Jeppa’s ongoing creation and two-and-a-half before the local council would demolish the complex – Villa Naturen resembles something of a driftwood summer cottage. In his dark suit and light felt hat, shaven yet skinny, Jeppa looks like an extra in his own life. (Hjelm: the builder is »an odd chap, not at all the waxwork that his mask would lead one to believe. He does everything on his own terms.«) The mood of the images implies both gumption and melancholy – like a distant relative to »Postman« Cheval of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. Buffeted by life yet resolute, he guides the photographer around his Scanian version of a palais idéal.

In one photo Jeppa, with a bushy moustache and his hands behind his back, strides forth like the lord of the manor; in the foreground a few lumps of wood lie in the wheelbarrow that he would cart around, constantly on the lookout for new materials. In another he sits on the bed in his bedroom. Here he wears an overcoat and hat, his hands resting meekly on his lap. As always, his facial features are expressionless. In the light from the window a statuette is outlined, of a stallion with no rider. Its muzzle is turned towards Jeppa, as though keeping watch over a deposed king. A placard or perhaps poster on the edge of the frame declares: All Year Round – DUX Radio.

The road to Neuschwanstein, 2025 | Photo: private

Those differences are easily multiplied. Take the topography, for example. In Bavaria I soon find myself a thousand metres above sea level, while in my childhood the other children and I would stomp around in the very silt of Råbelövssjön lake. Here and now the castle complex, with its knights’ house, chapel and other buildings, comprises an elevated ensemble that radiates an absolutistic inaccessibility; there and then the ramshackle construction invited play on a level with the groundwater. Neuschwanstein asserts a symbolic belonging to a sphere between the human and divine; Villa Naturen did the same, only with anything-but-elevated surroundings.

Neuschwanstein, 2025 | Photo: private

The total cost of Neuschwanstein, the design of which was initially sketched out by stage designer Christian Jank and then drafted by Eduard Riedel, former court architect to King Otto of Greece, is believed to have amounted to 6.2 million German gold marks, which at current exchange rates equates to almost one hundred times that figure in Swedish kronor today. What Villa Naturen eventually cost remains unknown, but reasonable guesses are unlikely to far exceed a modern-day minimum wage. Any earnings that Jeppa made on admissions that he didn’t personally need he would donate to the village priest in a bucket, with the request that it go towards Sunday-school activities and books and writing materials for the parish children.

When I reach the castle courtyard after a half-hour walk some twenty people are already waiting to enter. I hear American English, German, Italian, Japanese, a possible Norwegian dialect and what could be Slovene. Children jump up and down to keep themselves warm, parents take photos on their mobiles, and a man smokes at a slight remove from his party. It is early April, the tourists few.

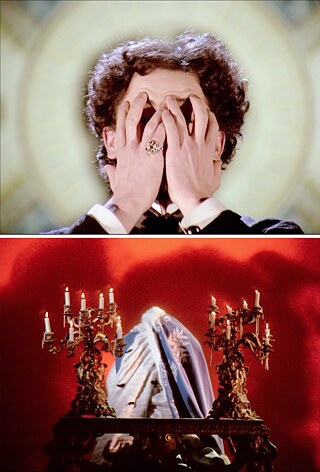

Neuschwanstein, watercolour, 1914 | Adolf Hitler

The debts that Ludwig II amassed, which plunged his Munich cabinet into despair and, combined with the king’s not altogether pronounced interest in political realities, contributed to his deposition, have thus long kindled what is now a flourishing industry. The castle from which the allegedly incapacitated regent was removed one rainy June night in 1886 proves that success is possible in failure. Or, as Lorenz Mayr, the manservant who remained loyal to his master to the last, states in Syberberg’s film, while standing on Marienbrücke with the castle behind his back: »But didn’t we all live on him? And not badly. And we still do.«

Unlike the majority of megalomaniacal constructions, this dream residence with its view over the Schwansee exudes no tyrannical nature, no thorny hierarchies nor fanatic’s wet dreams of expansion. If any monarch in the age of absolutism earned the epithet »aesthete«, it ought to be the temperamental Wittelsbacher. War and barracks life were not the business of Ludwig II. He was raised strictly and lovelessly, rode and fenced, but his personal preference was that the funds that the army of the Free State so direly needed to modernise its arsenal instead be invested in opera performances, singing societies and lavish modes of transport. A couple of lost wars later, and, following his brother’s breakdown after the Prussian king was, under Bismarck’s auspices, proclaimed the first emperor of the German Empire, Ludwig withdrew from the society of humans and animals alike.

Was it then that the lofty monarch with the soft features, sharp-fitting uniforms and the wave in his hair followed the example of the diminutive Scanian – who was yet to be born in Degeberga, but who three quarters of a century and two world wars later would pose in a shapeless suit with his hand on the gate to his dream plot, his intended sanctuary for care workers and minors? That is to say: Was it in reaction to his shortcomings in what was for Ludwig the closest he ever came to a professional life that he sought refuge in the more benign realm of art – or, as Wagner exclaims in the most recent film devoted to sexually ambivalent kings, intrigue and a thirst for beauty: »If art determines the world, will it replace politics?«

An oft-cited observation posits that communism responds to fascism’s aestheticisation of politics by politicising art. Even if Syberberg’s solitaire declares: »I have no possessions. What belongs to me belongs to everyone,« he was hardly inspired by Marxist pamphlets. And even if it would be another fifty years before a new Versailles Treaty gave rise to the stab-in-the-back myth exploited by revolutionary nationalists to mobilise the German masses of the twenties and thirties, there are few reasons to doubt that Ludwig II sought to parry his loss of power by elevating art to a site that hovered above the insulting antagonisms of the everyday.

For the brown and black ideologies that Walter Benjamin’s witheringly overcited conclusion addresses, idiom and markers of distinction revealed the essence of the totalitarian state. From the look of its helmets to the height of the columns in ministerial arcades and the wide-scale staging of a torchlight procession – a people was a body to represent, and a nation was created just as much through aesthetic interventions as through repressive regimentation.

The designs for Neuschwanstein speak to a view of art that elevates it to a religion. Insofar as they weren't sifted out before they even reached the drawing board, social aspects and collective relevance were subject to needs assessment. Of course, such a castle would be inconceivable without a form of government underpinned by hereditary power, but on the Allgäu clifftops art trumped not only the administration’s protests but also the public at large. Neuschwanstein was constructed not to demonstrate a despot’s power over his subjects or pre-eminence in questions of taste, but to offer refuge to a wounded soul. Although the very image of cultivation – even down to his chamois-leather-topped fingertips – Ludwig II, like a vastly more affluent »Grub«-Jeppa, dreamed of a world in which he would be sheltered – from the world. However, unlike the increasingly chloroform-addled, often intoxicated Bavarian who surrounded himself with canonised kings, dead knights and fictional minstrels, the Scanian actively sought to save nurses and children. Still, as long as the wider world kept its distance, for both men their sanctuaries fulfilled their most important task.

Where rules and resources no longer dictate the parameters of architecture, the imagination is its only limit. That and statics, perhaps. It is no wonder that these so profoundly different yet kindred endeavours were never completed. For both, the art of construction constituted a »frozen music«, to borrow Goethe’s famous definition from one of his conversation with Eckermann, only with the caveat that in this music the notes could never fade – be they, as with Ludwig II’s castle, part of a growing cycle of operas or, as in Jeppa’s case, more a case of free jazz.

During the half-hour-long guided tour of the areas of Neuschwanstein that were completed before the king was deposed – two thirds of the castle are said to still stand empty – we are led through the Byzantine-inspired throne hall, Ludwig’s private bedroom, a dripstone cave cloaked in a blueish gloom, his study and its great novelty of the age – a telephone – and the Singers’ Hall, whose chandeliers could hold six hundred candles. »Here he sat alone,« the guide explains wistfully, »in contemplation…« After a dramatic pause just short enough to avert a collective melancholy, she adds, pointing: »And for the young ladies among us – look!« Behind the velvet barrier rope, at the other end of the extravagantly decorated hall, a four-legged creature graces the wall. A unicorn. The animal rears with slender front legs, its golden horn twisting diagonally upwards. In the panel above, just below the vaulted ceiling, a swan nobly bows its head.

“Ludwig II. – Requiem für einen jungfräulichen König” (Ludwig: Requiem for a Virgin King) | directed by Hans Jürgen Syberberg, 1972

The reclusive Swede’s mission was also clear: to save a fragment of humanity from the end of the world. »Soon,« the older schoolboys claimed Jeppa would assure his visitors, while encouraging them to place their ear to a scrapped radio: »soon you’ll hear it.« Jesus had appeared to him in a vision; he knew what the future held in store. Sooner or later the Germans would land, and then Villa Naturen would have to offer sanctuary – primarily to the schoolchildren and the hospital staff who had cared for Jeppa. Beneath one of the buildings lay not only a concrete shelter, known as the Bomb Cellar, but also a cell for captive Nazis.

The archetype of this forest refugium couldn’t have been nobler: Noah’s ark. Jeppa viewed himself as a latter-day successor to the Jewish patriarch, chosen to salvage the human flotsam that would be necessary to build a better world after the flood. So he toiled from morning to night, convinced of humanity’s self-destruction. According to his neighbours, his axe and hammer could be heard on weekdays and weekends alike. Quite how Jeppa envisaged this rescue operation is uncertain, likewise whether it was still required after the capitulation of Hitler’s Reich in May 1945. Still, there is no denying that his creation calls to mind a catamaran-style houseboat temporarily towed ashore. On the cover of a more recent children’s book about him, authored by a Bavarian who had moved to the area and who writes »in a nice, gently philosophical tone,« white swans patrol the water in front of the building. The risk of German submarines is, presumably, minimal.

The kitchen at Neuschwanstein, 2025 | Photo: private

Architectonic swansongs or not: Jeppa’s and Ludwig’s mutually so different creations both appear the result of a regressive fantasy: they offer a »seat of longing« to which their masters could withdraw, to cite Dan Andersson’s poem on the theme. Raised for times other than those in which they were built, the residences were moored during their captains’ lives, protected and floating, ready to save those remains of humanity who knew what was good for them and ferry them to a wiser future.

What is it that Ludwig says in Visconti, whose film portrays him in a more balanced way than the others, when the man with the tall hat arrives to remove the monarch who has efficaciously been declared incurably insane from afar? »Ah!«

And Jeppa of Doomsday? »Soon you’ll hear it.«

»With time the consensus has come to be that utopias always run aground,« notes Enquist of the Swedes who between 1881 and 1914 emigrated not to the USA, to which so many others travelled, but to South America. He was particularly interested in the mine workers from his home region of Norrland, who, as losers in the aftermath of the general strike, had left a Sweden on the cusp of a new social order. Most of those who survived illness and hardship settled in southern Brazil, many along the Uruguay River that forms a natural border with Argentina – »as though a fragment of a planet had been spewed out in the convulsions of creation and carried off in a dizzying trajectory across the seas.«

In my search for information I find a photo of an immigrant family in the village of Guaraní, Rio Grande do Sul, taken around 1900. The image is small and grainy; only after further online searches do I realise that it has also been cropped. In it, the parents stand on either side of their children. The father, who is closest to the camera, has a broad-rimmed hat and a bushy white beard. The son beside him is around ten, and he wears short trousers and a buttoned-up blazer. Like his father, his arms hang at his sides, while his sister, who looks a few years older and is standing a few steps behind, holds her mother’s hand. Both women wear long dresses and have their hair tied up, the daughter’s adorned with bows. The family look as paupers did in their Sunday best almost anywhere in the world at that time.

What piques my interest is an X. Someone has drawn it on the siding by the window between the children. Since the distance between them is the greatest in the image, wide enough to fit an absent person, I get the impression that this sign marks a loss – perhaps of a middle child who has passed away. I start to fantasise, fancying that such a cross could also represent the regent who wanted to remain forever a mystery to himself and to others. Or Jeppa, for that matter, who struggled to spell and appears to have highlighted important passages in the Bible with the same mark – unlike most letters in the alphabet, X could not be written the wrong way. Indeed, could that symbol even be the simplest expression of a utopia? Here it is: the site currently missing from the map that will one day harbour all longing. Enquist: »Perhaps it was the case that if the utopia existed one could only glimpse it by searching where it wasn’t expected to be found, like a secret dream of a world adjacent to the one we touched.«

About such an existence, at once part of the prevailing order and yet alien to it, one had to remain silent. Like a heterotopia, or »other space«, it must remain an enigma to the unversed, a source of trust for the initiated. »It was to be kept secret,« Enquist stresses. For »naturally they had every right to close themselves off, to be silent. They had emigrated from our world to their own, utopian. That was a human right for the emigrants« – these exiles no longer deemed necessary to the old world, among whom even Ludwig II and Jeppa could be counted, each in their own complex way.

Those who discovered or invented such places were granted shelter from an existence marked by wars, demands and quandaries. Ultimately, I imagine that these scattered meteorite fragments – at least in the eyes of free-church Norrlanders, and surely those of the god-fearing masters of Neuschwanstein and Villa Naturen, too – all promised a fellowship of misfits. Under their aegis there was space even for those who didn’t make the cut in existing collectives. All of them together constituted a loose grouping of the excluded, one at once eccentric and radical. If such connections could be charted on a map, the constellation formed would probably behave in much the same free and mutable manner as the souls in each individual group, its binding principle neither kinship nor nationality but affinity.

In an essay on »floating«, Meteor, Joseph Vogl grapples with cultural- and historico-philosophical notions of »an unborn world, which persists like a crypt in the real, historical world.« He sees its uncertain nature not as a firm or fixed state, which the funeral chapel usually represents, but rather as a »falling-at-height, a simultaneous, dual motion of rising and falling« that signifies an »abaric, that is to say weightless, point« (from the Greek báros, »weight« or »burden«, in both the literal and figurative meanings). In this floating space, the Earth and the moon’s gravitational pull on one another are neutralised, and a state of weightless balance emerges. Here reigns, if one so desires, a power-free calm.

Most heterotopias, at least those of Ludwig II and Jeppa’s individualistic ilk, strive for this status. Conventional laws shall not apply. Quite the reverse; the »expansion of the space of possibility«, as Vogl writes, coincides »with the project of diminishing the weight of the world.« Through their unfinished states, both Neuschwanstein and Villa Naturen were placed in a quasi-permanent floating state. All still remained possible – new rooms or banqueting halls could be added, more towers and wings built, additional adornments applied… »As if,« Enquist notes, »that is also the only hypothesis with which we can live.«

The question is whether such places, as Vogl notes in reference to Kafka’s short story about the construction of the Great Wall of China, aren’t in actual fact »engaged in the production of the unfinished?« Through their celebration of the possible, they in practice renounce any claim to perfection.

Or are there different kinds of spaces of possibility? Twenty years after consigning Report from Mars to the scrapheap, I believe I can at least draw one lesson: while Ludwig II shows how one can become redundant as an acting power, a Jeppa learns how to make himself needed. Unlike Neuschwanstein, that gigantic molecule in solid stone that distanced itself from everything and everyone, the world was very much a part of Jeppa’s listing creation. With trees as its frame, his construction represented a physical state that refused to be separated from its immediate surroundings. (Hjelm again: »One probably couldn’t get any closer to nature than Jeppe [sic] did. The trees, for example, grow straight through the living room, nightingales warble in the crowns all through summer, and in the small lake, whose waves slosh playfully against the shore, he has his beloved pets – the crayfish!«)

For the German perfection was a question of money, while for the Swede it was not even a consideration – everything was to remain in a continuous state of creation, i.e. the state that chemists call in statu nascendi, »in the state of being born«, when the atoms’ tendency to react to their surroundings is far greater than once they have formed molecules. Ludwig II knew in advance what he wanted; Jeppa on the other hand never did. Neuschwanstein grew in a stable, calculated manner, while Villa Naturen branched off in capricious, surprising ways. Translated to literature: I prefer novels structured like Villa Naturen.

Swedish immigrants in Guaraní, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, postcard, around 1900 | Photo: The Royal Society for Swedish Culture Abroad

The reverse of the postcard tells a different story. On it, a joker in March 1958 writes to friends in Gothenburg that he and his party have had a »wonderful day, with breakfast in Damascus, lunch in Amman, a swim and coffee at the Dead Sea, and dinner in Jerusalem.« The printed text on the front reveals that he has happened across a card in the series The Life and Works of Swedes outside Sweden, published by what had then been known as the Royal Society for the Preservation of Swedishness Abroad, headquartered in Gothenburg. After a long day’s travelling, the cosmopolitan can’t resist a jaunty quip about the portrait: »The photo is of our travellers outside the hotel in Cairo.«

At first this discovery riles me; I had liked the cross much more when unexplained – when it still signified a conceivable absence, a shapeless loss, forever a mystery to all. Then it strikes me that the sender takes a not insignificant liberty. Not only does he read his own presence into the image many years after the fact; he also moves the travel party’s temporary residence from one continent to another. In extended spaces of possibility, at least, a cross can be placed anywhere.

Literature as the reverse of everything?

Cheval’s palais idéal in south-eastern France, Jacques Lucas’s maison sculptée in the north-west… Casa de Pedriñas in A Veiga, Galicia … Hearst Castle in California, and Horace Burgess’s enormous tree house (complete with basketball court and chapel) in Tennessee… or Neuschwanstein and Villa Naturen… Refuges where aesthetic considerations trumped the political agendas are many, scattered across space and time. In almost all of them, misfits have sought to ensconce themselves in their otherness. The power of their vision seems to be directed both backwards and forwards; their gaze travels through the ages, back to an order that perhaps never existed – as is the case with Ludwig II, who wished to re-create the medieval world of chivalry that had captivated him so in Wagner’s breakthrough opera about Lohengrin, the Knight of the Swan who defends the wrongly persecuted. But the misfit’s gaze also looks forwards, towards the post-destruction era of which Jeppa dreamed, one free from war and suffering, where the outsider could finally be an insider.

In its ideological form, this dual gaze is hardly unproblematic. Like any self-glorifying slogan in the vein of Make X, Y or Z Great Again, it harks at once to the conservative and futuristic. Although driven by a backwards-looking spirit, it promises a greatness that is also of the future. This reactionary futurism trivialises the now as a Gordian knot of diverse interests that is screaming out for the sharp blade of disruption. Only on the other side of the chop will the new erstwhile greatness be conceivable again.

In its idiosyncratic form, however, this dual gaze is nevertheless required in order to probe the point, the »compacting of the possible« in Vogl’s words, at which greater powers cancel one another out. There a conceivable heterotopia emerges, one that floats peacefully between Ludwig’s »Once…« and Jeppa’s »Soon…«, between a liberating height and breathtaking depth – abarically.

»I doff my hat,« sings the freight guard while the thunder rumbles in Dan Andersson’s iambic pentameter, »and greet life’s frigid parting night.« He then concludes his poem with the exhilaration that alone counterbalances the destruction present:

A feast beckons, the hour of parting nigh,

When, saved and free, I cease to apprehend,

and, striding down to meet the nameless dark –

exult, collapse, smile and am no more.

Between what has been and what may come, high and low, solid and liquid – in the critical now: there are worse intersections to use as one’s point of departure in writing. Andersson might describe that point as the temporary »seat of longing«. Though perhaps an X would also suffice.

The space rock whose fragments were scattered over eastern Allgäu in April 2002 likely originated from the same body as a meteorite that had struck in Czechia barely half a century before, in April 1959. Isotope analyses have proven that the Czech rock is twelve million years old, while Neuschwanstein is four times older. If they did originally belong to the same comet, it must therefore have been heterogenous – a composite of all manner of slag held together by the forces of gravity that split upon collision with another celestial body.

I imagine such diverse meteorite fragments as Villa Naturen and Neuschwanstein, or for that matter the Swedish colony in Guaraní, originating from the same greater longing to which Andersson alludes in his poetry. Then it would not be too late even for failed or foundering, sloppy or rejected materials to be put to use again. There would always be the possibility of finding »on the scrapheap, in what never was,« as Enquist writes, »the beginnings of something altogether different.«