Drawn to the scene of the crime

Hunting serial offenders

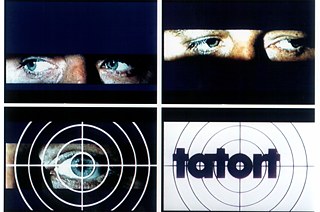

Every Sunday evening, around ten million people settle down in front of the telly to watch the German police procedural, Tatort, or “crime scene” in English. Regional mysteries and thrillers are also flying off the shelves in bookstores. So what is it that makes a good murder mystery so riveting?

By Nadine Berghausen

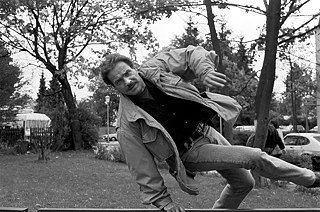

Night has fallen and we find ourselves in a pitch-black forest. The only sound is the victim’s gasping breath as she stumbles through the underbrush in the dark. Terrified, she glances back over her shoulder in the direction of her pursuer. Suddenly she stops, as the horrible realisation of who the killer is registers on her face in the final moments of her life…

Although scenes like this have flickered over the television screen innumerable times before, the mystery-loving viewer still catches her breath and quickly runs through a mental list of the suspects while cuddling deeper into the sofa with a pleasurable shiver of fear. Prime time at 8:15 p.m. on Sunday, when the latest Tatort goes out over the airwaves, is a must for German murder mystery fans. Produced jointly by German broadcaster ARD’s nine affiliates, Swiss broadcaster SRF and Austrian broadcaster ORF, it has been a reliable crowd pleaser for decades. Since the very first episode in 1970, Tatort has been a Sunday evening ritual for many Germans and a ratings darling for broadcasters that draws a loyal viewership of around ten million viewers each week. The series follows a number of crime detecting duos in various locations, and viewer favourites like Chief Superintendent Thiel from Münster and his moody partner Professor Boerne, or tough detective Lena Odenthal from Ludwigshafen, can drive ratings even higher.

The feel-good factor

So just what is the secret to the murder mystery’s continuing popularity? There are a number of possible explanations. Some classify mysteries and thrillers as “feel-good literature” because the reader knows he is secure behind his book as he watches gruesome events unfold from a safe distance. Another important factor is the sense of satisfaction a viewer or reader feels if she can solve the case before the final resolution on the page or screen.

The regional mystery–“Hey, I know that crime scene!”

Regional crime stories are booming in Germany. Canny detectives chase domestic murderers through the Allgäu, the Eifel, and East Friesian, and authors and screenwriters also take their crime scenes abroad to holiday hotspots, whisking readers away to Murder on Mallorca, Bloody Brittanyor perhaps Tatort Tuscany. These imaginary titles hint at the often cliché-ridden content of such mysteries, which sometimes even border on the slapstick. To keep the action fairly manageable, the setting is generally in a rural idyll instead of the impersonal, interchangeable greyness of the big city. It is easier to untangle the intricacies of social structures in the macrocosm of a village.

Thrill and reality

While truth may sometimes be stranger than fiction, it is not in crime fiction. In 2017 around 3,500 mysteries and thrillers were released on paper, plus all the television shows being churned out on a regular basis. Happily there were only 405 real murder victims in the Germany in the same year.

If Canadian experimental psychologist and linguistic Steven Pinker’s study of the history of violence is to be believed, then the present day is much less violent than previous eras. So how does this relate to the rising wave of enthusiasm for mysteries and thrillers? In his 1,200 page book The Better Angels of our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, Pinker, who lecturers in psychology at Harvard, argues that violence has considerably declined throughout human history. He suggests that we celebrate violence in the modern age because it is absent from our real lives. Like the popular spectacle of public executions in the Middle Ages, we turn to fictitious post-mortems to get our violence fix today.

Interestingly, in 2017 the number of bodies in Tatort also dropped by almost 50 percent, from 162 corpses the year before to just 85.