My Hermann Hesse Moment

Not for Everybody

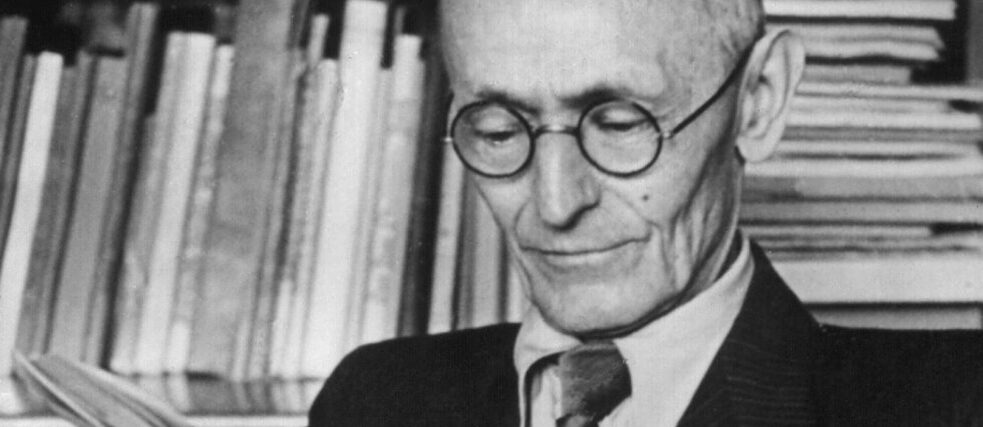

Hermann Hesse cultivated being an outsider throughout his life and yet expressed what we all feel. Dead now for 50 years, he still has much to say to us about the crisis of modern humanity. My Hesse Moment

By Sarah Maria Deckert

On the gradually yellowing fly-title of my paperback edition of Gabriel García Márquez’s 100 Years of Solitude is a handwritten note: “Read something sensible for once!” My social studies teacher had left this well-intentioned note there and vigorously thrust the book into my hand without comment. I should read it. Firstly, because he thought it was worth reading. And secondly, because he wanted to show me the difference between authors who were worth reading and those less worth reading.

His scorn was directed at Hermann Hesse. In a passionate monologue, I had tried to defend Hesse’s work with unflinching vehemence against his, to my mind, baseless verbal abuse in a noisy Irish pub on the study trip to Brussels just a week before. Obviously, he didn’t think it was very sensible. In any case, I did the same, bought Steppenwolf in the nearest bookshop, no doubt wrote something similarly well-intentioned on the inside and threw the edition at his feet the next day. (Not really, of course; after all, he was my teacher – and a good one at that. But I would have liked to have thrown it.)

Since then, at least, I know what I didn’t think was possible at the time: People are different. There are Hesse critics like my former social studies teacher using the well-known argument that you can only read Hesse during your youth and again in old age. And even then, they say, they get tired of his eternally identical canon, this hopelessly romantic, esoteric, kitschy world-averse prose, which they’d already seen enough of in Casper David Friedrich’s paintings and now gratuitously has to read. “Strange to walk in the fog! / Life is loneliness. / No person knows the other, / each one is alone.”

And then there are those Hesse disciples like me who will pay eternal homage to the messianic Swabian because he once led them to the light. Those who inhale his books, one after the other, until everything is inside, all the magic.

And as with every epiphany, there is also this moment with Hesse. I had mine at 14. A good friend lent me a splendidly bound edition of Siddhartha. And because she said you had to have read it, and because I trusted her judgment, I withdrew with it and tried to immerse myself in the Indian Poem of 1922. I didn’t understand a word. I let Govinda’s story rest for two years, then gave it a second try. No other book on my shelf today is so well-worn.

Stefan Zweig is said to have visited Hermann Hesse once and entered the house in such a rush of euphoria that a wooden beam on the low ceiling knocked him right down. When you enter Hesse’s world for the first time, reading him is much the same. His words knock you down, rob you of your senses, are literary opium that carries your consciousness up into spheres you didn’t even know existed before. The rest is a creed that you either profess or not: either you step over the threshold or you remain standing before it, an eternal onlooker at Hesse’s magic theatre.

Entrance not for everybody

– not for everybody.

The understander of misunderstood youth

The real paradox of Hermann Hesse is that he expressed what we all feel, we, the misunderstood youth with our cosily warm world-weariness, with our loneliness and our love’s sorrow in which we wallow so extensively. Yet throughout his life he was not really there for anyone. Not for his three wives, not for his children. He stayed away from his mother’s funeral altogether – out of spite. What other reason could there have been for Hesse? He was only moderately capable of empathy, this miserable narcissist. A restless soul, he roamed about and whenever he could, he fled, shed his skin, switched women, places and roles, step by step. Book by book, he wrote himself a second reality, a parallel world into which he could slip, like under a blanket. A world he created to better bear the real one, through which he sometimes moved so clumsily. Like no other, he knew about the dialectic of being an outsider and defended the individual against any kind of massification, against any promise of happiness that societal life wanted to make him believe.

The rebellious finger that Der Spiegel flipped him in its last issue on the 50th anniversary of the writer’s death is perhaps a bit much. But Hermann Hesse nevertheless carried a kind of mark of Cain quite clearly in front of him. With it, he wanted to free himself from the conventional straightjacket of his generation. For me, however, he was never the provocative rebel; always more the elegiac hermit, the steppe wolf, Friedrich’s Monk by the Sea.

The question that always concerned him was that of human destiny. His story then led him along winding paths to his own self, somewhere in the backwoods of India, where he quietly hummed “om” by a river. Searching for Hesse therefore meant searching within oneself, listening to oneself, with the courage of self-will. As he wrote in 1917: “For a man there is only one natural standpoint, only one natural criterion. And that is self-will.” That was good advice even then. And today, in times when the institutional machinery of globalisation wants to make everything the same, giving birth to this wretched uniformity, his message could not be more topical.

Hesse’s work read to me like one great cry for soul and meaning, for love and rebirth. His novels are parables, legends and adventure journeys, always with this sensitive urge, with this glow that everyone carries somewhere within themselves. To this day I don’t know whether my social studies teacher ever subsequently understood this fascination. Maybe he’s had his Hesse moment by now. Maybe it will come. Or maybe not. Hesse is not for everybody.