1968, students around the world protested against authoritarian structures and social injustice. A closer look at Mexico and Germany reveals the transnational connections of this movement.

1968 stands for counterculture, youthful rebellion, and student revolt. In cities like Paris, Berlin, Prague, New York, Warsaw, and Mexico City, students took to the streets to fight for human rights and social justice. Through demonstrations, street theater, lecture hall occupations, flyers, and newspapers, they sparked political change in their respective countries. Students also faced severe state repression.Although the movement’s specific goals and political demands varied widely from country to country, a comparison between Mexico and Germany shows how the 1968 student movement was shaped by a spirit of internationalism – an ideal that people should unite across borders to work toward a more just world.

Mexico: Resistance and Repression Ahead of the Olympic Games

In 1968, Mexico was set to become the first Latin American country to host the Olympic Games. As the government prepared for this major event, students from the Autonomous University in Mexico City took to the streets to protest social inequality. Despite the so-called “Mexican Miracle” – a period of economic growth since the 1940s – the newly acquired wealth was not distributed fairly across social classes. At the same time, the authoritarian policies of the ruling PRI party under President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz increasingly restricted freedom of speech and assembly.With the Olympics approaching, the Mexican government viewed the protests as a threat to its desired image of domestic stability. Throughout 1968, students faced escalating repression, including military raids on university campuses, arrests, and police violence. In solidarity, parents, teachers, and workers joined the protests, swelling the movement to half a million people. Just days before the Olympics began, state violence culminated in the Tlatelolco Massacre on October 2, in which around 400 people were killed. In 1971, the violent repression of student protesters from the 1968 movement continued with the mass killing known as “El Halconazo,” carried out by members of the Halcones, a government-backed paramilitary group. Both events remain deeply embedded in Mexico’s collective memory.

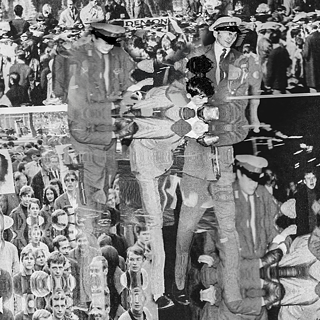

Digitally edited scanography of a student arrested by the police | © Eriza Visual - @eriza.visual / @polansky.rodriguez

Germany: The 1968 Movement’s Break with Old Structures

In Germany, the state and police also responded harshly to the protests of 1968. The public shooting of student Benno Ohnesorg during a 1967 protest is considered the founding moment of the student movement, which reached its peak following the assassination attempt on Rudi Dutschke in April 1968. Students demanded national education reforms, press freedom, and greater political participation in universities. They called for a thorough reckoning with the Nazi era, including the dismissal of faculty with Nazi affiliations. At the same time, their demands expanded to transnational issues such as ending the Vietnam War and expressing solidarity with anti-imperialist movements.By 1969, the protests in Germany had begun to fade, fragmented by internal conflicts and the lack of a unified political direction. Yet despite representing a societal minority, the movement’s demands had a lasting impact. Education reforms were implemented, and the movement paved the way for later anti-nuclear, feminist, and environmental movements.

Digitally edited scanography of oppressed students | © Eriza Visual - @eriza.visual / @polansky.rodriguez

International Solidarity: Comparing Germany and Mexico

The movements in both countries shared key positions, such as the demand to end the Vietnam War, seen as a symbol of imperialist oppression and capitalist exploitation. Another parallel was the emergence of intellectual currents and student groups advocating for the democratization of universities and society. The 1968 movement also reflected an accelerating globalization, as international networks of students and activists formed through exchange programs. Protest styles and tactics were transmitted across the Atlantic. The global nature of 1968 stems not only from shared ideological foundations but also from a new political and collective self-awareness that students around the world embraced.A purely national perspective is insufficient to fully grasp the international waves of protest in 1968. The 1968 movement only becomes comprehensible when its national, regional, and global dimensions are seen as interconnected and interdependent.

The Aftershocks of ’68

The student movements of 1968 have become part of the collective memory in many countries and serve as a key historical reference point for today’s sociopolitical movements. In Mexico, the Tlatelolco Massacre remains a symbol of state repression in 1968 and 1971. Tlatelolco and the violent disappearance of 43 students from Ayotzinapa in 2014 continue to symbolize the lack of government accountability and the ongoing impunity of those responsible.In Germany, students and young people remain central actors in sociopolitical change, which also exposes them to increased state violence. The call for international solidarity – for example, through ending German arms exports to war zones – remains as relevant today as it was in 1968.