Drawn in by bargain real estate, they’re wedged into bustling corner plazas or nestled between vacant retail spaces – storefront churches. The sacred and the profane in a marriage of convenience. But they are far more than just austere places of worship, as our author had to realize.

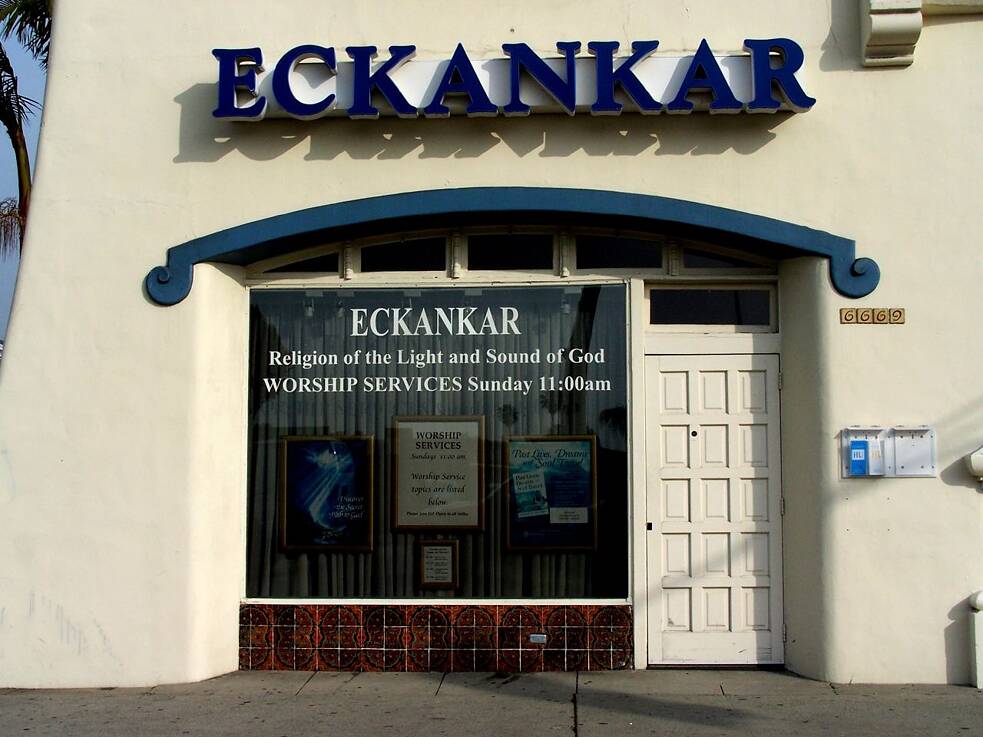

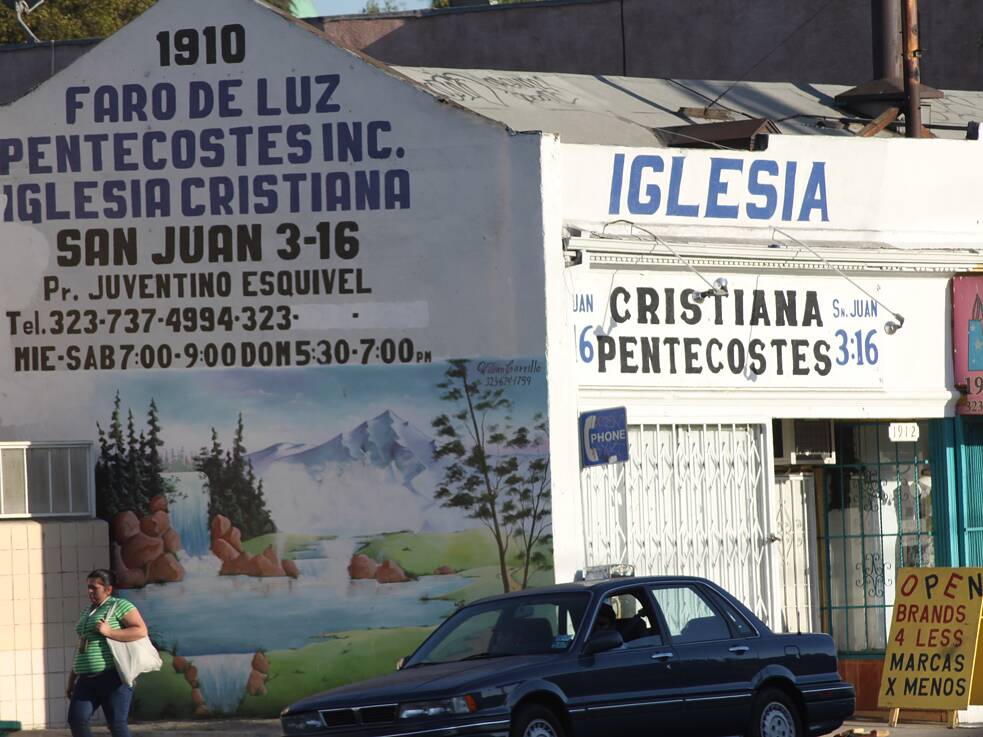

I first noticed them a few months after moving to Los Angeles from Germany. Among the many novel sights and sounds, this urban streetscape fixture caught my eye. Found all over the city, these places of worship frequently feature hand-painted signage, evocative names in a variety of languages and humble furnishings. Most often, they share threadbare mini-mall real estate with convenience stores, laundromats, small eateries and such.To me, they stood out for their stark contrast to the decidedly more ostentatious church architecture I was used to growing up; especially those buildings considered to be art historically important, associated with hundreds of years of genteel history, with well-known architects and artists. I was fascinated by these strip mall sanctuaries, intrigued and amused.

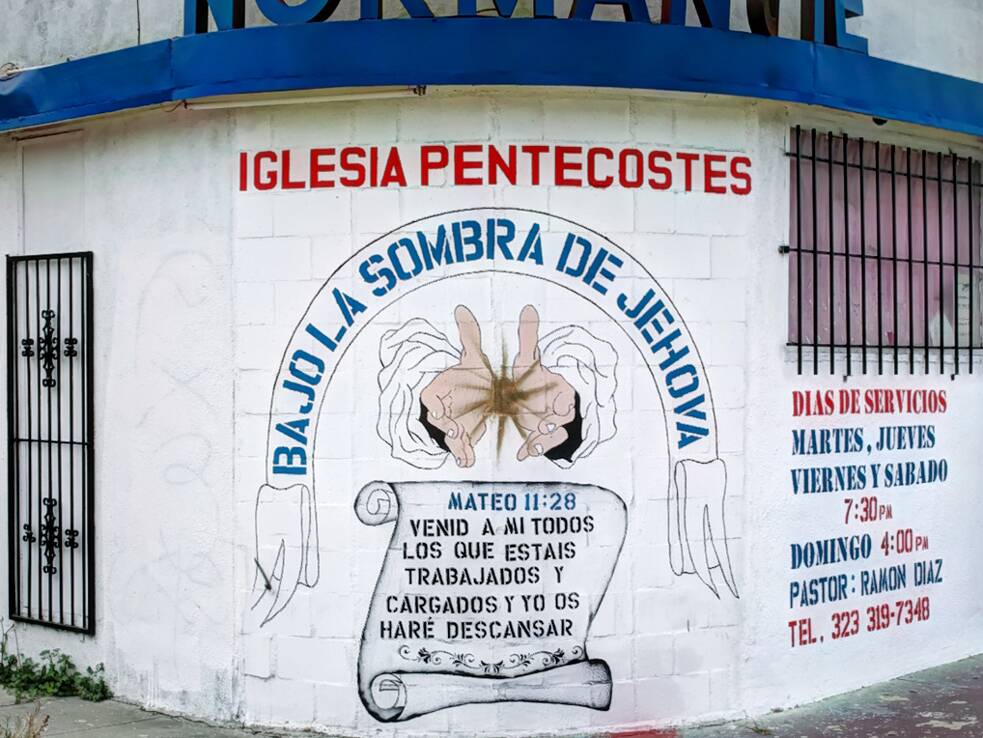

Though strikingly ubiquitous in Los Angeles, storefront churches can be found across the country. They spread north and west during the Great Migration in the early 1900s, when up to six million descendants of enslaved people left the South and built new communities from scratch. Even so, storefront churches have deep ties to our city as most of them are rooted in pentecostal Christianity. And that particular approach is closely linked with downtown L.A., specifically, the Azusa Street Revival of 1906. Widely recognized as a key catalyst for modern-day Pentecostalism, this multi-year revival led by the preacher William J. Seymour helped kick off a movement that keeps growing exponentially and globally – closing in on the Catholic church in Latin America and gaining a strong foothold in Africa.

Pentecostalism is an ecstatic practice of Christianity, decentralized and often focused on charismatic preachers. Compared to the hierarchical and institutionalized religion of yesteryear, there can be a sense of freedom and radical potential. Seymour’s revival allowed racially integrated worship during the height of Jim Crow – a good example of how churches can provide spaces of conditional freedom within oppressive environments. Such as when enslaved people weren’t allowed to assemble, worship often was the sole exception. Or when centuries later, Protestant churches in the German Democratic Republic provided refuge and helped spark the peaceful revolution culminating in the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The Second Great Migration in the 1940s brought Black Southerners to Los Angeles, while the city served as a gateway for millions of new immigrants for the remainder of the century. The immigration reform act of 1965 allowed for more immigrants from Asian and Latin American countries, while shortly after, brutal wars in Central America sent thousands of refugees north. Storefront churches sprung up among these new communities, as havens of material and spiritual solidarity for people living at the margins, supporting tenuous survival in a new world.

Of course, storefront churches attract parishioners for the same reasons as religion has since time immemorial: They promise belonging, meaning, material support and a spiritual home, be it in the northern destinations of the Great Migration or in immigrant communities of 20th and 21st century Los Angeles. Many times, I’ve walked by sounds of music, smells of fresh food wafting and groups of people congregating. Enticed by the sense of warmth and community, I would quickly realize that I’d stumbled upon a storefront church. At their best, storefront churches are independent hubs of solidarity. But their promise of freedom, decentralization and dismantling of old hierarchies can turn into a prosperity gospel-fueled predatory business model. Those seeking solace may find exploitation, when their leaders line their pockets in a confluence of American entrepreneurialism and religion.

In contemplating storefront churches, something else stood out to me: The dynamics of my own response to this – for me – cultural novelty. And I wondered about what triggered my amusement. Was the discrepancy of these modest abodes and their big spiritual ambition the cause for snark? A sense of superiority, perhaps? Was I unconsciously aligning myself with the higher value assigned to the religious architecture of my upbringing? I have just as little spiritual connection to those old buildings as I do to the storefront spaces, making them both purely cultural or art-historical artifacts. This way, the two types are, in a sense, just as foreign to me as they are to each other. And yet, in their dissimilarities, they each represent universal human needs and longings.

Today, as I interrogate my perspective in observing these spaces of grassroots solidarity, I find another truth: Initially encountering the storefront church, I saw its “otherness,” its novel and sometimes, to me, amusing elements. But now, I also see in it people surviving and thriving through community in difficult circumstances. In noting the bias of my gaze, I realize that authentic solidarity can only ever grow from one person to another, aware of their common humanity and of any power dynamics. When I acknowledge diverseness among us, along with our shared needs and humankind, then I understand “solidarity as the recognition of our inherent interconnectedness, an attempt to build bonds of commonality across difference,” as the authors of a new book on the concept put it (Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor, Solidarity: The Past, Present, and Future of a World-Changing Idea). I now know that solidarity can only exist among equals. By recognizing our distinction along with our likeness, we can grow beyond the easy alignments of our various in-groups. When I don’t objectify, but instead observe from the knowledge of our similarities, then I can allow for fascination, for communication and for authentic solidarity – from one human subject to another, without objectification and exoticizing. Along the way, the humble storefront church as a locus of solidarity has, accidentally, become a lesson in true solidarity for me.