With the slogan “Lost in the 90s,” the retrospective celebrates an exciting decade of film – in cooperation with the Goethe-Institut.

The Berlinale has always had a good understanding of symbolism. For the first time, one of the venues for this year's retrospective is the E-Werk, an old industrial ruin that was a techno club in the 1990s. The films, which bring to life an extremely innovative decade that seems almost unreal from today's perspective, deal with demolition and new beginnings, as well as disappearance. The turning point around 1990 brought not only the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet empire. Independent cinema also flourished and, thanks to digital technology, soon had unlimited possibilities. Films such as Slacker (Richard Linklater, USA 1990) and Boyz n the Hood (John Singleton, USA 1991) presented Generation X and Black Cinema. And indeed, many other films come to mind – “Anything goes” was the motto of the decade. But of course, in the end, the Berlinale is once again all about Berlin.Berlin: Adventure Playground for Filmmakers

In 1990, the walled city was not yet a construction site, but a veritable desert. On the former death strip between East and West, world history condensed into absolute nothingness – and this idea magically attracted filmmakers from all over the world. For his film essay Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro (Deutschland Neu(n) Null / Germany Year 90 Nine Zero; Germany/France 1991), Jean-Luc Godard reactivated his secret agent Lemmy Caution: 73-year-old Eddie Constantine searches for a way to the West and finds only ghosts of the past. In a much better mood, an unemployed Soviet soldier wanders around the wastelands of Potsdamer Platz in Dušan Makavejev's Gorilla Bathes at Noon (Yugoslavia/Germany 1993).

Anita Manćić and Svetozar Cvetković in “Gorilla Bathes at Noon”. Director: Dušan Makavejev | Photo: © Deutsche Kinemathek / von Vietinghoff Filmproduktion

Conceived by the new director Heleen Gerritsen in cooperation with the Goethe-Institut, the section also pays tribute to queer cinema. This has long been present at the Berlinale, but a film as wild as Prinz in Hölleland (Prince in Hell; Michael Stock, Germany 1993) seems almost inconceivable today. This gay punk fairy tale set in the Kreuzberg scene features a trouserless harlequin as a nasty puppeteer, the slaughter of a chicken and rough sex in a coal cellar – all on drugs, of course. In comparison, Lola und Bilidikid (Lola and Billy the Kid; Germany, 1999) seems almost tame. Yet Kutluğ Ataman's touching drama about a gay coming-out in a Turkish migrant context remains a timeless classic, a milestone for queer cinema as a whole.

Wolfram Haack in „Prinz in Hölleland” (Prince in in Hell). Director: Michael Stock | Photo: © Salzgeber

Risen From Ruins, and Gone Again

All of Europe was in turmoil during those years, as evidenced by Harun Farocki's Videograms of a Revolution (Germany, 1992) about the fall of the Ceaușescu regime and Želimir Žilnik's documentary-grotesque Tito Among the Serbs for the Second Time (Yugoslavia, 1994). In retrospect, some of it seems eerie, as war is back, distant and yet familiar. But the spirit of optimism prevails, the images connect and evoke the most amazing associations: did Wolfgang Becker copy the famous scene in Good Bye, Lenin, in which a statue of Lenin is being removed, from a colleague? It appears in exactly the same way in Gorilla Bathes at Noon, ten years earlier, and in a documentary, no less.

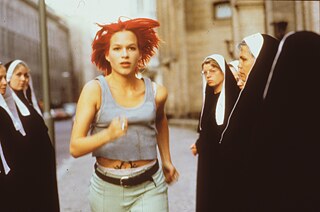

Franka Potente in “Lola rennt” (Run Lola Run). Director: Tom Tykwer | Photo: Deutsche Kinemathek, © X-Verleih

February 2026