Sinema Transtopia is more than a cinema – it sees itself as a space for discourse, film culture and neighbourhood. But what does a cinema look like when it aims not just to show films, but to become a place of encounter?

Berlin is in full Berlinale fever. Even in Wedding, far from the festival center at Potsdamer Platz, you can feel it. It’s late January, and the cold stubbornly clings to the courtyards. Artist and cultural manager Malve Lippmann walks, wrapped in layers, toward the place she calls her living room. Following close behind her is Can Sungu, filmmaker and curator. “Meyhane,” he says as we make our way to the living room.In Turkish, “Hane” can be a space for many things. At SİNEMA TRANSTOPIA, it is exactly that: a shape-shifting space that turns the cinema into a place of encounter every Friday and Saturday.

Sinema Transtopia Returns as Part of “Berlinale Goes Kiez”

This neighborhood cinema is tucked away in a courtyard in Wedding. The motion sensor flickers like a strobe light as the two approach the entrance. At the door, Can Sungu gently straightens the curtain. Both look a bit exhausted from the Berlinale press screenings, but there's plenty of reason to be excited.Because since 2010, the project “Berlinale goes Kiez” has brought selected festival films to different cinemas across the city. And Sinema Transtopia is part of it again—now for the third year in a row. But how do you run a neighborhood cinema that aims not just to show films, but to bring people together?

Meyhane is inspired by transnational food cultures, sharing small dishes together in a convivial atmosphere. | © Marvin Girbig

From Artist Studio to Courtyard Cinema

Their story begins like this: After finishing their studies at the Berlin University of the Arts, where they wrote their master’s thesis together, they found a small studio in Wedding, right on Prinzenallee. Thirty-six square meters, huge glass windows. It’s the early 2010s, a time when Berlin was solidifying its cultural status. Little by little, more people poked their heads in, asking what this place was for. They started hosting small events—gatherings, shared meals, evenings spent together. And at some point, the idea came: Why not make it a cinema?“We didn’t rent it with the intention of hosting public events,” says Lippmann. “It just evolved.” This way of becoming part of the urban fabric isn’t a marketing strategy at Sinema Transtopia—it’s their origin story. Even the name of their association—bi’bak, Turkish for “come have a look”—is meant literally: Berlin comes in, Wedding comes in.

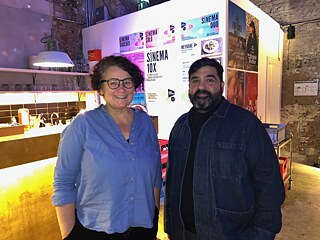

In their living room: Sinema Transtopia directors Can Sungu and Malve Lippmann | © Daniel Hinz

They didn’t name the place Transtopia because it sounds cool or looks good on posters, but because it perfectly describes what happens here: a space where connections form across borders. Through film, but just as much through what happens before and after. The term comes from migration scholar Erol Yıldız. Cinema co-director Can Sungu sees it as something they actively live here—utopia and the in-between. And that is exactly why this cinema feels the impact more strongly when cultural policy suddenly treats spaces like this as a “nice-to-have.”

Cultural Budget Cuts Threaten Independent Cinemas Like Transtopia

In 2024, Berlin’s new CDU/SPD government conducted a major budget overhaul, setting new priorities and a new fiscal logic—and the cuts hit the cultural scene hard. Lippmann says the news hit them “quite abruptly at the end of the year.” The result: less money, a difficult year. But Berliners stand by their cinema. Lippmann talks about the 10-ticket pass. Ten tickets, each for seven euros, and the key feature: not personalized, fully shareable. “You can come with nine friends,” she says, as if it were the most obvious thing in the world. In a time and a city where everything is subscription-based, sharing becomes a tiny counter-ideology.As we talk, the room slowly fills. People squeeze in at our table. Two guests in Adidas tops share a mezze platter, chatting in Turkish about films. Sungu shifts over; Malve is already deep in conversation with two others. Bringing people together isn’t a marketing slogan here—it’s lived reality. And this shows in the film selection, too: the program isn’t chosen by the two directors, but by the Sinema Transtopia team.

More than just a cinema: Sinema Transtopia creates spaces where film culture and discourse are shared and further developed. | © Lucía Alfaro

Migrant, Marginalized and BIPoC Perspectives

Sungu emphasizes: they’re not “anti”—they’re “open to many things.” But they want to center perspectives often missing from German cinema: migrant, marginalized, and BIPoC positions. And that leads to his anti-category stance: no “Iranian Film Days,” no “Turkish Film Week.” Instead: themes and concepts that connect people and bring them together.They often screen their films with English subtitles—simply because the audience is so international. At the same time, their language policy is open: German, Spanish, Turkish, sometimes whispered translations.

Lippmann greets the person who will be moderating the next film and seems genuinely moved: “It’s so wonderful who walks through our door. They stand before you with their ideas, their convictions, and shape our cinema in the most beautiful ways.” While outside, the motion sensor light flickers rapidly, inside Sinema Transtopia it’s time for: curtains up, film on

February 2026