Embracing the algorithmic mindset

Algorithms are not strangers to the art of filmmaking. Most of the time they play a role imperceptible to the viewer, yet they are essential for telling stories and, even more, explore the fringes of film language.

Algorithms are key to making films as we know them. From blockbusters like Star Wars to experimental cinema like Arnulf Rainer by Peter Kubelka, thinking with algorithms has been of huge importance to filmmakers. But before diving deeper into this idea, better start with a simpler question that often we tend to undermine: What is an algorithm?

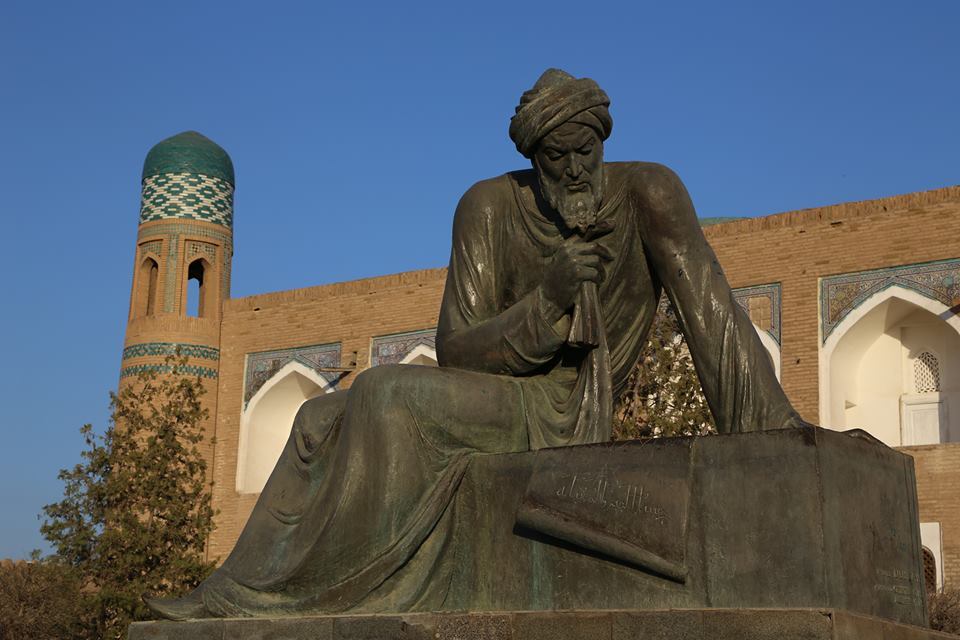

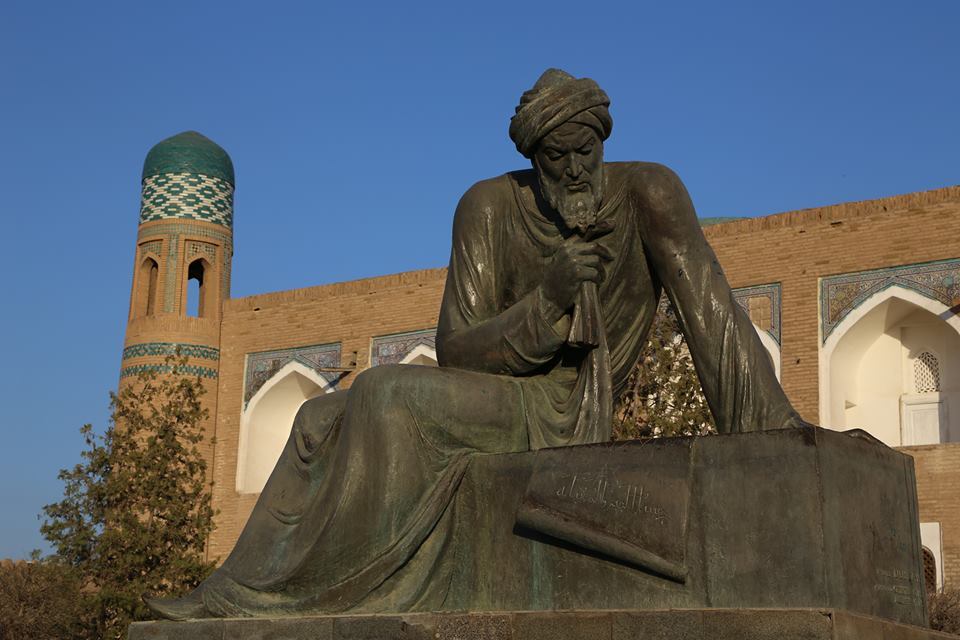

Now strongly linked to the science of artificial intelligence, the word algorithm originally comes from 9th-century Persian polymath Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, or as he was known in Latin, Algoritmi. In one of his major contributions to human knowledge, a book that introduced the principles of algebra, he gave step-by-step instructions on how to solve mathematical problems. These instructions included how to multiply or divide large numbers, and how to solve equations, amongst others. These recipes, though essential to algebra, did not have a specific name. That is how scholars ended up referring to them as the work of Algoritmi, or, in short, algorithms.

In this sense, we can say that human culture consists of millions of interconnected algorithms that help us communicate, share knowledge and believe in the existence of a stable and somewhat predictable reality. Algorithms are involved in all kind of activities, from the execution of menial work, such as tying shoelaces, to highly complex activities, like eye surgery; from the very sensual, like wine tasting, to the highly intellectual, like writing a book. Statue of Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in his birth town Khiva, Uzbekistan

| Photo: Yunuskhuja Tuygunkhujaev, CC BY-SA 4.0

For each of these situations, algorithms provide an actionable blueprint for our individual experiences. They suggest what to do, when and how to react in order to reach the intended goal and share the knowledge that comes from such experiences. Even highly spiritual activities, such as praying, meditating, or making love are shaped by social algorithms that help us confirm our experiences with others, empathize and feel connected. Contemplating the world in this manner is what I call an algorithmic mindset.

Statue of Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in his birth town Khiva, Uzbekistan

| Photo: Yunuskhuja Tuygunkhujaev, CC BY-SA 4.0

For each of these situations, algorithms provide an actionable blueprint for our individual experiences. They suggest what to do, when and how to react in order to reach the intended goal and share the knowledge that comes from such experiences. Even highly spiritual activities, such as praying, meditating, or making love are shaped by social algorithms that help us confirm our experiences with others, empathize and feel connected. Contemplating the world in this manner is what I call an algorithmic mindset.

When it comes to the kind of stories that populate cinema, one of the most famous algorithms is the so-called Hero’s Journey, or monomyth. This algorithm is centered on a main character, called the hero, who proceeds through a sequence of life-changing adventures wherein he confronts his deepest inner fears, eventually returning home as a stronger and wiser person.

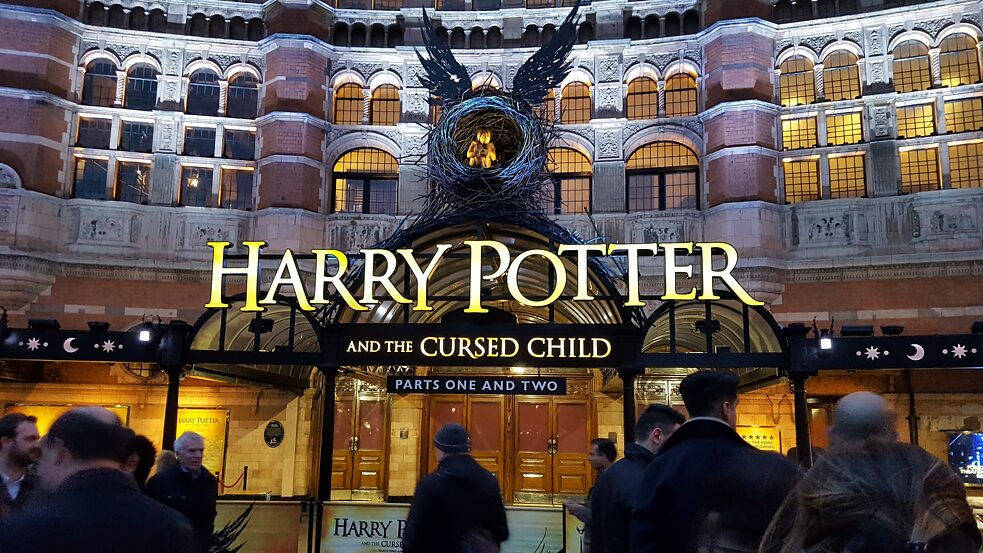

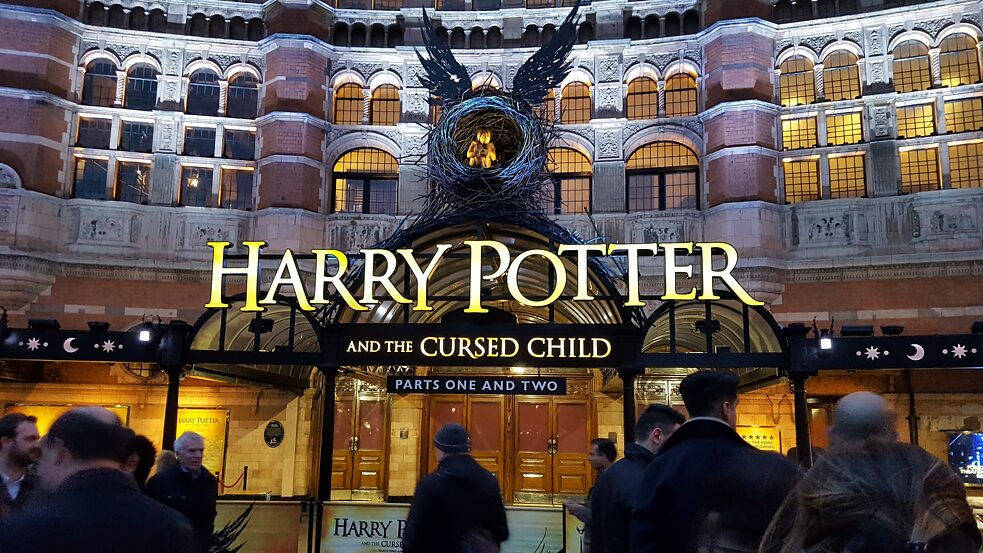

The monomyth is based on the work of mythologist Joseph Campbell, who identified this algorithm in stories that were at the core of many cultures, like Jesus in Christianity, Moses in Judaism, and Buddha in Buddhism. This is probably the reason why characters who play the hero’s role, such as Luke Skywalker, or Harry Potter, end up being so empathetic for most spectators. It is not about who they are, not even what they represent (they could be either good or evil and it would still have the same emotional effect). It’s all about the algorithm these characters follow, and how this algorithm taps into our human emotions. The Harry Potter storyline proved a winner with fans around the world

| Photo Credit: Elizabeth Jamieson / Unsplash

The Harry Potter storyline proved a winner with fans around the world

| Photo Credit: Elizabeth Jamieson / Unsplash

Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer (1960) is an early example of this kind of cinema. The film makes use of an algorithm to orchestrate an audiovisual symphony composed of black frames, white frames, noise and silence. For Kubelka, these four elements contain the material essence of cinema: light, darkness, sound and silence.

Arnulf Rainer is composed with a mix of metric precision and artistic intuition. The film consists of 16 sections, each one lasting precisely 24 seconds (576 frames). Each section is composed of “phrases” or small units that span 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 16, 18, 24, 36, 48, 72, 96, 144, 192, or 288 frames.

In each of these phrases, Kubelka experiments. If a phrase is made of two frames, for instance, he chooses one of the sixteen possible combinations between black, white, noise and silence. The same with four frame phrases, and so on. The result is a provocative audiovisual piece that translates the abstract notion of algorithm to an audiovisual experience designed to be watched on a film screen.

Another example of an algorithmic film is Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (1966), above. Physically similar to Kubelka’s work, The Flicker consists of sequences of black and empty frames projected at high speed. As the film progresses, the fast combination of blacks and whites start to cause optic impressions which simulate colors and forms. While this happens, the film is said to produce hallucinatory effects that are triggered not by the senses, but by the brain itself.

Conrad, who took courses on neurology during his studies at Harvard, was aware that the flickering effect could produce the impression of parallel frequencies of light in a similar way as musical overtones are created inside the brain. His intention with The Flicker was to find the right algorithmic composition that, making use of the most basic elements of cinema, would trigger these visions in the spectator.

As a final example of algorithmic filmmaking, I want to mention Hollis Frampton's Critical Mass from 1971. In the film we see a couple arguing while the scene is constantly intervened by abrupt cuts that slightly jump cut to previous moments of the same scene, giving a sense of being trapped in a perpetual dialogue. This idea is emphasized by Frampton's separate treatment of sound and images, which causes the dialog to gradually loose sync with the characters’ performances.

Pablo Núñez Palma

| © Third Eye Media

Critical Mass introduces an algorithm that deconstructs the drama between two characters in order to illustrate how in these sort of quarrels we lose ourselves in our own monologues. We could think of this algorithm literally as a film strip moving back and forth through a projector. That said, the question of when the film will go forward or backward seems to be a more complex determination.

Pablo Núñez Palma

| © Third Eye Media

Critical Mass introduces an algorithm that deconstructs the drama between two characters in order to illustrate how in these sort of quarrels we lose ourselves in our own monologues. We could think of this algorithm literally as a film strip moving back and forth through a projector. That said, the question of when the film will go forward or backward seems to be a more complex determination.

Gaining awareness of the algorithmic mindset that exists outside of the domain of computers can help us demystify the idea of algorithms as something complex and intellectually ungraspable.

At the same time, exploring the art of filmmaking through the mindset of algorithms can remind us that every algorithm, digital or mental, story oriented or experimentation oriented, is the result of human ingenuity. Some of them may have been created and others discovered, but they all respond to the ultimate need of humans to solve a problem, and in doing that, try to make sense of the world.

Learn more about Pablo Núñez Palma's views on the future of creative AI here.

Now strongly linked to the science of artificial intelligence, the word algorithm originally comes from 9th-century Persian polymath Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, or as he was known in Latin, Algoritmi. In one of his major contributions to human knowledge, a book that introduced the principles of algebra, he gave step-by-step instructions on how to solve mathematical problems. These instructions included how to multiply or divide large numbers, and how to solve equations, amongst others. These recipes, though essential to algebra, did not have a specific name. That is how scholars ended up referring to them as the work of Algoritmi, or, in short, algorithms.

An age-old technique

But if we think outside the realms of mathematics, it is not hard to notice that algorithms have been part of human culture even before al-Khwarizmi described them in his book. In fact, they can be traced back to the very beginnings of human civilization. As Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths claim in their book Algorithms to Live by, “an algorithm is just a finite sequence of steps used to solve a problem.” When someone cooks dinner, or knits a sweater, or puts “a sharp edge on a piece of flint by executing a precise sequence of strikes with the end of an antler” (a key development for the manufacture of tools during the stone age), or when anyone does anything that requires following a pre-established series of actions aimed at a specific goal, that person is following an algorithm.In this sense, we can say that human culture consists of millions of interconnected algorithms that help us communicate, share knowledge and believe in the existence of a stable and somewhat predictable reality. Algorithms are involved in all kind of activities, from the execution of menial work, such as tying shoelaces, to highly complex activities, like eye surgery; from the very sensual, like wine tasting, to the highly intellectual, like writing a book.

Statue of Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in his birth town Khiva, Uzbekistan

| Photo: Yunuskhuja Tuygunkhujaev, CC BY-SA 4.0

For each of these situations, algorithms provide an actionable blueprint for our individual experiences. They suggest what to do, when and how to react in order to reach the intended goal and share the knowledge that comes from such experiences. Even highly spiritual activities, such as praying, meditating, or making love are shaped by social algorithms that help us confirm our experiences with others, empathize and feel connected. Contemplating the world in this manner is what I call an algorithmic mindset.

Statue of Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in his birth town Khiva, Uzbekistan

| Photo: Yunuskhuja Tuygunkhujaev, CC BY-SA 4.0

For each of these situations, algorithms provide an actionable blueprint for our individual experiences. They suggest what to do, when and how to react in order to reach the intended goal and share the knowledge that comes from such experiences. Even highly spiritual activities, such as praying, meditating, or making love are shaped by social algorithms that help us confirm our experiences with others, empathize and feel connected. Contemplating the world in this manner is what I call an algorithmic mindset.

Algorithmic mindset in film

Through the lens of this mindset, we can see that the tradition of filmmaking and film viewing is rich in algorithmic diversity. Just as there is an algorithm for a successful visit to the cinema (1. entering a cinema, 2. buying tickets, 3. matching the theater number with the number printed on the ticket, etc.) there is also an array of storytelling algorithms that have proven to be effective in tapping human emotions and reaffirming the narratives on which our culture is based.When it comes to the kind of stories that populate cinema, one of the most famous algorithms is the so-called Hero’s Journey, or monomyth. This algorithm is centered on a main character, called the hero, who proceeds through a sequence of life-changing adventures wherein he confronts his deepest inner fears, eventually returning home as a stronger and wiser person.

The monomyth is based on the work of mythologist Joseph Campbell, who identified this algorithm in stories that were at the core of many cultures, like Jesus in Christianity, Moses in Judaism, and Buddha in Buddhism. This is probably the reason why characters who play the hero’s role, such as Luke Skywalker, or Harry Potter, end up being so empathetic for most spectators. It is not about who they are, not even what they represent (they could be either good or evil and it would still have the same emotional effect). It’s all about the algorithm these characters follow, and how this algorithm taps into our human emotions.

The Harry Potter storyline proved a winner with fans around the world

| Photo Credit: Elizabeth Jamieson / Unsplash

The Harry Potter storyline proved a winner with fans around the world

| Photo Credit: Elizabeth Jamieson / Unsplash

Arnulf Rainer: an early algorithmic film

Aside from the mainstream film industry and its use of cultural algorithms to stir up our feelings, there is a smaller subset of film works that, instead of using algorithms to tell stories, explore the aesthetic dimension of algorithms, putting them as the main characters of their narrative.Peter Kubelka’s Arnulf Rainer (1960) is an early example of this kind of cinema. The film makes use of an algorithm to orchestrate an audiovisual symphony composed of black frames, white frames, noise and silence. For Kubelka, these four elements contain the material essence of cinema: light, darkness, sound and silence.

Arnulf Rainer is composed with a mix of metric precision and artistic intuition. The film consists of 16 sections, each one lasting precisely 24 seconds (576 frames). Each section is composed of “phrases” or small units that span 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 12, 16, 18, 24, 36, 48, 72, 96, 144, 192, or 288 frames.

In each of these phrases, Kubelka experiments. If a phrase is made of two frames, for instance, he chooses one of the sixteen possible combinations between black, white, noise and silence. The same with four frame phrases, and so on. The result is a provocative audiovisual piece that translates the abstract notion of algorithm to an audiovisual experience designed to be watched on a film screen.

Black and empty frames

Another example of an algorithmic film is Tony Conrad’s The Flicker (1966), above. Physically similar to Kubelka’s work, The Flicker consists of sequences of black and empty frames projected at high speed. As the film progresses, the fast combination of blacks and whites start to cause optic impressions which simulate colors and forms. While this happens, the film is said to produce hallucinatory effects that are triggered not by the senses, but by the brain itself.

Conrad, who took courses on neurology during his studies at Harvard, was aware that the flickering effect could produce the impression of parallel frequencies of light in a similar way as musical overtones are created inside the brain. His intention with The Flicker was to find the right algorithmic composition that, making use of the most basic elements of cinema, would trigger these visions in the spectator.

As a final example of algorithmic filmmaking, I want to mention Hollis Frampton's Critical Mass from 1971. In the film we see a couple arguing while the scene is constantly intervened by abrupt cuts that slightly jump cut to previous moments of the same scene, giving a sense of being trapped in a perpetual dialogue. This idea is emphasized by Frampton's separate treatment of sound and images, which causes the dialog to gradually loose sync with the characters’ performances.

Pablo Núñez Palma

| © Third Eye Media

Critical Mass introduces an algorithm that deconstructs the drama between two characters in order to illustrate how in these sort of quarrels we lose ourselves in our own monologues. We could think of this algorithm literally as a film strip moving back and forth through a projector. That said, the question of when the film will go forward or backward seems to be a more complex determination.

Pablo Núñez Palma

| © Third Eye Media

Critical Mass introduces an algorithm that deconstructs the drama between two characters in order to illustrate how in these sort of quarrels we lose ourselves in our own monologues. We could think of this algorithm literally as a film strip moving back and forth through a projector. That said, the question of when the film will go forward or backward seems to be a more complex determination.Gaining awareness of the algorithmic mindset that exists outside of the domain of computers can help us demystify the idea of algorithms as something complex and intellectually ungraspable.

At the same time, exploring the art of filmmaking through the mindset of algorithms can remind us that every algorithm, digital or mental, story oriented or experimentation oriented, is the result of human ingenuity. Some of them may have been created and others discovered, but they all respond to the ultimate need of humans to solve a problem, and in doing that, try to make sense of the world.

Learn more about Pablo Núñez Palma's views on the future of creative AI here.