What are AI-driven music recommendation tools doing to us?

Just like countless other online entertainment platforms, music streaming services use artificial intelligence to push us towards songs that we will like. How the technology works and what it’s doing to our listening habits will change music forever.

If you ask Stephan Baumann, the AI-driven recommendation tools in common use across the world today had their beginnings in a quirky technology of the late 1970s called Grundy. This offline system recommended books to readers after they answered a series of questions and then matched them to a particular personality stereotype.

Decades ahead of its time, it was arguably the forerunner to Amazon’s well known book and product recommendations which appear at the bottom of their sales pages or even get sent to customers, sometimes unsolicited, via email.

But what works for books (and movies too, by the way) also works for music, so it’s no surprise that by the start of the 2000s, scientists at a number of universities around the world were scrambling to develop music recommendation systems, driven by AI, that could be rolled out online.

According to Prof. Baumann at Germany’s Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI), when the music industry first got wind of what was happening they were “not amused at all.” They were concerned it was going to destroy their industry’s model of talent-spotting, rights ownership and mega profits. In retrospect, they were right to be concerned.

Streaming platforms like Spotify have revolutionised how we listen to music

| Photo credit: Heidi Fin / Unsplash

Streaming platforms like Spotify have revolutionised how we listen to music

| Photo credit: Heidi Fin / Unsplash

Some 40% of users on Spotify use the app in an “open” mindset, which means they are receptive to listening to recommended content on the basis of their previous listening behaviour. Through buttons like “Discover”, “Radio”, “Related Artists” or “Now Playing,” listeners have the option to click on recommended content. The streaming giant also collates songs of similar styles into its popular playlists, carrying titles like “Monster Dance Hits” or “Indie Arrivals.” Around a third of all listening time on the platform is spent on Spotify-generated playlists.

After initially using a comparatively simple music recommendation system, Spotify bought the technology expertise of The Echo Nest in 2014, a standout group of US researchers, and started to actively employ AI technology that would feed their users exactly what they wanted. It’s even been reported that the company now commissions non-existent bands to write songs to order, which land straight on its playlists - although Spotify vehemently denies this.

Either way, in the new music marketplace, no matter what streaming service you use (whether it’s free or costs you money) your every move is being logged. It’s no wonder that many record labels now partner up with Spotify and other music streaming services to get the latest data on what songs are working well with listeners. Shazam a song at lunch yesterday? It's already been logged in a database somewhere

| Photo credit: Nick Fewings / Unsplash

Shazam a song at lunch yesterday? It's already been logged in a database somewhere

| Photo credit: Nick Fewings / Unsplash

“System recommendations and algorithms are a great tool, but they do feed on your own musical preferences, creating a feedback loop that encourages you to listen to music that is similar to music you already like,” he explains.

“It is not unlike social media filter bubbles, which present contents that are in-line with the way we already view the world.”

For Professor Jamie Sherrah, from the University of Adelaide’s School of Computer Science, there’s also the issue that music streaming services like Spotify or Apple Music, which give us access to millions of songs in seconds, devalue modern music.

“There is such a vast variety and a continuum of styles and songs, it can trivialise the talent and creativity that went into a piece of music,” Sherrah says.

While AI-driven tools enable us to find the music we love faster, it also shifts us away from the shared experience of enjoying music together too, Sherrah adds.

“Among the plethora of artistry on offer, people tend to gravitate towards a music sub-culture of specific genres, artists and values, with the benefit that it can be very specific and configurable.”

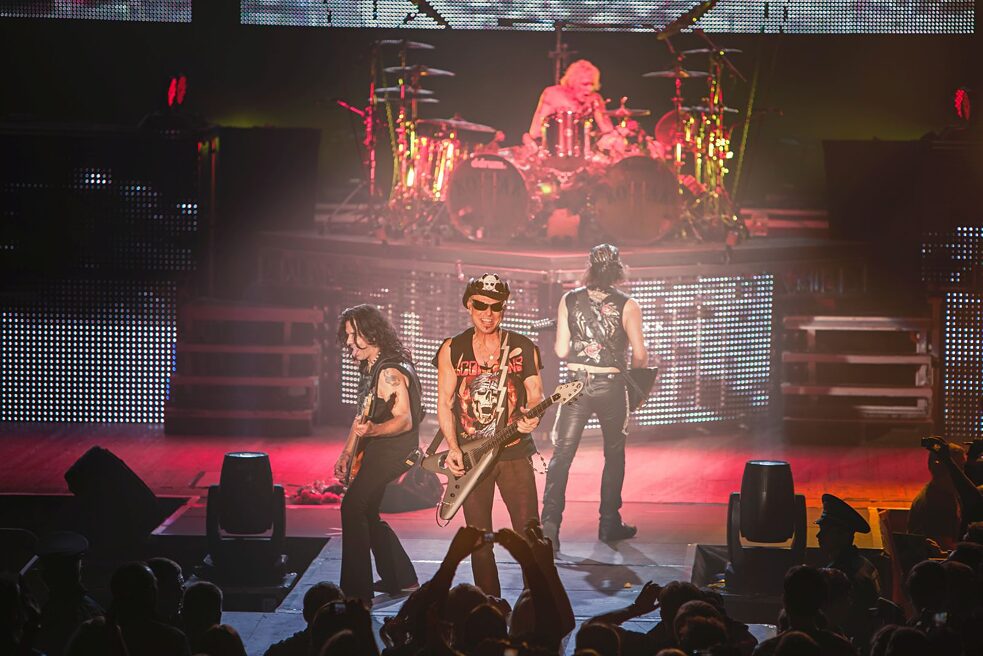

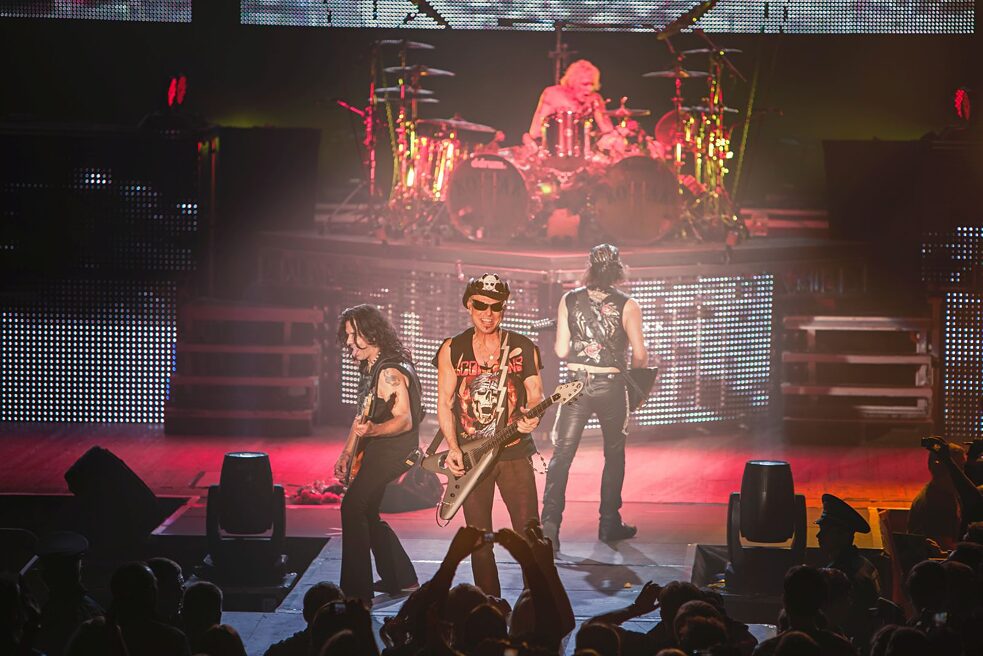

Jamie Sherrah says music fans now tend to focus on a particular sub-culture of specific genres

| Photo credit: Colourbox

Professor Daniel Shanahan, from Ohio State University, believes that music itself is getting punchier and shorter, due to humanity’s transition to an “attention economy.” That theory proposes that as content has grown increasingly abundant and immediately available online, attention becomes the limiting factor in the consumption of information.

Jamie Sherrah says music fans now tend to focus on a particular sub-culture of specific genres

| Photo credit: Colourbox

Professor Daniel Shanahan, from Ohio State University, believes that music itself is getting punchier and shorter, due to humanity’s transition to an “attention economy.” That theory proposes that as content has grown increasingly abundant and immediately available online, attention becomes the limiting factor in the consumption of information.

“Constant connection changes how we behave in the moment,” he concludes.

“For me, it’s just a very, very advanced tool,” he says. “A drum machine, a sampler, AI-generated music - it’s okay. I’ll still have fun with my music machines, creating my own songs.”

“The point is why? I mean, the machine does not have an in-built feeling of life or death.”

Hubert Léveillé Gauvin also doesn’t think our growing reliance on AI-driven recommendation systems will spell the end of our musical autonomy. He says we just need more time to work out how to use these musical tools the right way.

“I do believe that, as the technology and the users mature together, we will make use of these technological innovations to broaden our musical universe, not restrict it.”

Stephan Baumann, Hubert Léveillé Gauvin and Jamie Sherrah share thoughts about the future of creative AI on their network profiles.

Decades ahead of its time, it was arguably the forerunner to Amazon’s well known book and product recommendations which appear at the bottom of their sales pages or even get sent to customers, sometimes unsolicited, via email.

But what works for books (and movies too, by the way) also works for music, so it’s no surprise that by the start of the 2000s, scientists at a number of universities around the world were scrambling to develop music recommendation systems, driven by AI, that could be rolled out online.

According to Prof. Baumann at Germany’s Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI), when the music industry first got wind of what was happening they were “not amused at all.” They were concerned it was going to destroy their industry’s model of talent-spotting, rights ownership and mega profits. In retrospect, they were right to be concerned.

Streaming platforms like Spotify have revolutionised how we listen to music

| Photo credit: Heidi Fin / Unsplash

Streaming platforms like Spotify have revolutionised how we listen to music

| Photo credit: Heidi Fin / Unsplash

Streaming rather than buying

Fast forward 15-20 years and the moving parts of the worldwide music industry have completely changed. Some of the major record labels still exist, but they now get most of their income from streaming, via services like Spotify or Pandora.Some 40% of users on Spotify use the app in an “open” mindset, which means they are receptive to listening to recommended content on the basis of their previous listening behaviour. Through buttons like “Discover”, “Radio”, “Related Artists” or “Now Playing,” listeners have the option to click on recommended content. The streaming giant also collates songs of similar styles into its popular playlists, carrying titles like “Monster Dance Hits” or “Indie Arrivals.” Around a third of all listening time on the platform is spent on Spotify-generated playlists.

After initially using a comparatively simple music recommendation system, Spotify bought the technology expertise of The Echo Nest in 2014, a standout group of US researchers, and started to actively employ AI technology that would feed their users exactly what they wanted. It’s even been reported that the company now commissions non-existent bands to write songs to order, which land straight on its playlists - although Spotify vehemently denies this.

Either way, in the new music marketplace, no matter what streaming service you use (whether it’s free or costs you money) your every move is being logged. It’s no wonder that many record labels now partner up with Spotify and other music streaming services to get the latest data on what songs are working well with listeners.

Shazam a song at lunch yesterday? It's already been logged in a database somewhere

| Photo credit: Nick Fewings / Unsplash

Shazam a song at lunch yesterday? It's already been logged in a database somewhere

| Photo credit: Nick Fewings / Unsplash

Listening on (feedback) loop

Montreal-based music analyst Hubert Léveillé Gauvin believes that since that early 2000s, AI-driven music tools have changed how we consume music. He fondly describes the early days of Apple’s “Genius” playlist-making algorithm as a “pocket-size musical expert” for instance. But, all this technology at our fingertips comes with a catch, he says.“System recommendations and algorithms are a great tool, but they do feed on your own musical preferences, creating a feedback loop that encourages you to listen to music that is similar to music you already like,” he explains.

“It is not unlike social media filter bubbles, which present contents that are in-line with the way we already view the world.”

For Professor Jamie Sherrah, from the University of Adelaide’s School of Computer Science, there’s also the issue that music streaming services like Spotify or Apple Music, which give us access to millions of songs in seconds, devalue modern music.

“There is such a vast variety and a continuum of styles and songs, it can trivialise the talent and creativity that went into a piece of music,” Sherrah says.

While AI-driven tools enable us to find the music we love faster, it also shifts us away from the shared experience of enjoying music together too, Sherrah adds.

“Among the plethora of artistry on offer, people tend to gravitate towards a music sub-culture of specific genres, artists and values, with the benefit that it can be very specific and configurable.”

Jamie Sherrah says music fans now tend to focus on a particular sub-culture of specific genres

| Photo credit: Colourbox

Professor Daniel Shanahan, from Ohio State University, believes that music itself is getting punchier and shorter, due to humanity’s transition to an “attention economy.” That theory proposes that as content has grown increasingly abundant and immediately available online, attention becomes the limiting factor in the consumption of information.

Jamie Sherrah says music fans now tend to focus on a particular sub-culture of specific genres

| Photo credit: Colourbox

Professor Daniel Shanahan, from Ohio State University, believes that music itself is getting punchier and shorter, due to humanity’s transition to an “attention economy.” That theory proposes that as content has grown increasingly abundant and immediately available online, attention becomes the limiting factor in the consumption of information.“Constant connection changes how we behave in the moment,” he concludes.

Personalised music

Stephan Baumann believes that within a decade, each of us will be listening to personalised music, composed just for us using the power of AI. Technology already exists that can turn pre-existent song databases into new songs, so why couldn’t a similar tool be used to create something from our online music listening history? Baumann, a part-time musician himself, doesn’t see it as a “dystopian future” though.“For me, it’s just a very, very advanced tool,” he says. “A drum machine, a sampler, AI-generated music - it’s okay. I’ll still have fun with my music machines, creating my own songs.”

“The point is why? I mean, the machine does not have an in-built feeling of life or death.”

Hubert Léveillé Gauvin also doesn’t think our growing reliance on AI-driven recommendation systems will spell the end of our musical autonomy. He says we just need more time to work out how to use these musical tools the right way.

“I do believe that, as the technology and the users mature together, we will make use of these technological innovations to broaden our musical universe, not restrict it.”

Stephan Baumann, Hubert Léveillé Gauvin and Jamie Sherrah share thoughts about the future of creative AI on their network profiles.