Usually sung by either men or women (never together), the Daynane is inherent to the Amazigh population of the region and an ancestral cultural practice. The music is tightly related to social events like deaths, births and weddings while often tackling taboos, like love and sex. The lyrics are very open and direct. Whereas a number of male bands from the region have taken the Daynane to regional stages, women’s performances are usually reserved for social events.

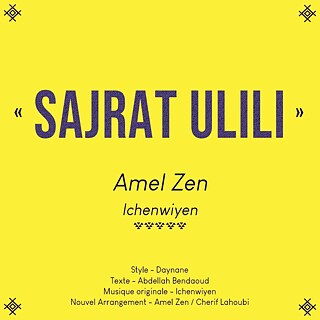

After futile attempts at finding recordings of the Daynane that predate the 1970s, the artist resorted to the internet, working with it as an open-source archive. She chose a live recording of the iconic 70s Amazigh band Ichenwiyen called Sajrat Ulili (The Oleander Tree),that was one of the first bands to record this style (after Chikh Tanga, but unfortunately it was not possible to find any recording of his work). The lyrics of the song were written by acclaimed Algerian Amazigh thinker and poet Abdallah Bendaoud.

Reworking the old recording in the studio, the artist added her own vocals and instrumentation, creating a lively conversation between two generations of artists who have never met, but who deliver the same message: A quest for freedom and identity. Her work also brings both male and female performers together for the first time in the recorded history of the Daynane, opening the debate around gender diversity. The music exhibits strong ties to nature, manifested in the lyrics and instrumentation. It can be heard through the sounds of the Ajaaboubte, which is an old Amazigh wind instrument made of the ghalim plant and used in west Algeria and parts of Morocco, in addition to the percussion made out of wood and animal skins.

Amel personalised the composition of the song to her own musical interests by adding electro-pop elements, while maintaining the original choruses and sounds. Listeners can detect the differences between the two eras of recording through the mixing of sound and music, giving continuity to the Daynane.

After researching the Daynane and working on this project, Amel reflects on her findings saying:

“I believe that it is very important to get cultural practitioners to engage around their work during their lifetime while it is still possible. The notion of cultural heritage should also evolve in the collective socio-cultural memory. Heritage does not necessarily mean old: It is created and redefined every single day, and no-one is more qualified than its custodians to testify to it.”

Duration: 3’27

Composer: Ichenwiyen إيشنوين

New Arrangement: Amel Zen, Mohamed Cherif Lahoubi

Original instrumentation: guitar, harmonica and banjo

Lyricist: Abdellah Bendaoud

Instruments: Synthesizers, electric guitar and bass

Date of original composition/work: Late 1970s

Recorded: June 2021

Daynane

Amel Zen – Interview with Abdellah Bendaoud, lyricist of Sajrat UliliWorking on the track Sajrat Ulili, Amel decided to conduct an interview with the original lyricist, Abdellah Bendaoud, to shed more light on the meaning and context of the Daynane. This was especially important for the artist, due to the lack of materials available about Daynane’s musical heritage despite its presence since the 19th century at the very least. Researching the style was hence a challenging task.

“With this interview, I wanted to focus on the definition of Daynane and its impact as a musical cultural heritage through the lens of one of its performers. Interviews with authors like Abdellah Bendaoud can provide us with plenty of information and insights, as the authors themselves become the subject of a contemporary archive.”

The Why Behind the Music

A Strong Witness of the History of People and Identities – Amel ZenSince the dawn of humanity, humans felt the need to express themselves, communicate, and leave a trace of their existence. From rock drawings to building resilient empires, humans followed this need for expression to build their history and civilisation. Today, these material monuments are labelled “material cultural heritage”. Alongside the static and visible empires, there is another type of heritage: A stronger and living heritage that survives with life and humanity through its vital bond to the senses and sensations. This is called intangible heritage.

Our fascination with the power and impact of sound and music on life since the dawn of time and the question of intangible cultural heritage are at the core of what I do. Through my work I explore the intimate relation between heritage and social, cultural, historical and political life in an attempt to better understand my local community and the wider global community.

Drawing on my North African, Maghrebi and Amazigh heritage, my music reflects my learnings and impressions over a decade of musical production. My work is aimed at building bridges between humans and cultures while at the same time respecting our differences from the perspectives of ethnicity, religion, culture and gender as an Algerian, Amazigh, North African and a citizen of the world.

In North Africa, the different colonisations and nihilistic political projects such as Pan Arabism attempted to erase the Amazigh identity and culture. Spawning confusion between ethnicity and religious or linguistic belonging, Pan Arabism included North African countries in a general, single cultural entity: the Arab world. Consequently, diversity was banished and the native Amazigh populations repressed. Despite these adverse conditions that the Amazigh population has been through, our musical heritage in North Africa persisted through oral transmission. After years of protest and struggle, and in respect for the memory and demands of those martyred in the 1980 Berber Spring and the Black Spring of 2001 in Kabylia in Algeria, and adhering to the demands of fighters and activists in Morocco as well, we managed to make Tamazight an official recognised language. Yet there is still more to be done to highlight our culture.

My activity within the sphere of musical cultural heritage is a continuation of the struggle for Amazigh culture and identity in the region, as I believe that there is an urgent need to rehabilitate the history of peoples and their identities. It is more than an act of preservation; it is an act of resistance and survival, a duty to remember.

Related Links

-

YouTube

November 2021