Wohnungsnot in Berlin und Toronto

Housing

Der Mangel an günstigem Wohnraum hat sowohl in Europa als auch in Nordamerika derzeit seinen absoluten Höhepunkt erreicht. In dieser Folge beschäftigt sich Tomma Suki am Beispiel von Toronto und Berlin mit der zunehmenden Wohnungsnot auf beiden Seiten des Atlantiks.

Diese Folge anhören: Apple Music | Spotify | Download

Dieser Beitrag wurde von Tomma Suki und Ayosha Kortlang produziert, die als Designer*innen in Berlin leben und arbeiten. Sie sind Gründungsmitglieder von Torhaus Berlin e.V., ein selbstverwalteter Community Space,und eine Ideenplattform für Projekte, die sich mit kreativen Formen der städtischen Teilhabe und des gemeinsamen Gestaltens auseinandersetzen. Zu Torhaus Berlin e.V. gehört auch der von Ayosha gegründete Community-Radiosender THF Radio. In dieser Folge spricht Tomma mit Expert*innen zum Thema Wohnungsbau und Wohnraumentwicklung. Außerdem kommen Aktivist*innen in Berlin und Toronto zu Wort, die von der Wohnraumkrise in ihren Städten berichten. Die Musik in dieser Folge „Lost Places“ stammt von Matteo Haal. Die Fotos zu dieser Folge wurde von Gordon Welters in der Wagenburg Lohmühle Berlin aufgenommen.

Transkript

[MUSIC]

Jürgen “Zosch” Hans: For 30 years, I was a punk, and we are living outside normal society. And we want to try to find a place, where we can live how we want.

Tomma Suki: Housing means shelter, security, and provides an identity and lifestyle. Housing is a basic human need. Housing is a privilege. How we live has changed a lot in the past decades and will continue to change. If we don’t act now, cities will grow and become more and more dense and the few affordable spaces that remain, will disappear. In this episode, we want to take a closer look at Berlin’s housing situation and its unique history as the city has gone through major political and economic changes in the recent past. We spoke with people who have an understanding of these changes to get a glimpse of the broader picture of what has led to the precarious housing situation that we find today. This is Tomma Suki from Berlin with THE BIG PONDER.

Jürgen “Zosch” Hans: We find some people who have the same idea. And of course, we are punks, we say, we squat in this place. We don’t want to pay rent or like this. We are free people. And why only the people who have big money should have an area like this? Because we have the money to buy it. We think we have also the right to have a place in this town to do our thing and so we do it.

Tomma Suki: From 1961 to 1989, the Berlin Wall divided the city into West and East Berlin. This political situation shaped the city and made it an unattractive option for investors. But the affordable space and the uncertain political conditions made the city attractive for young people, artists, musicians, punks, and those who felt the counterculture best represented their desired form of life. The Wagenburg Lohmühle is a project that was created shortly after the Wall fell and still exists today. It’s a kind of trailer park but in the middle of the city. It’s in between a street and a canal and surrounded by plants and trees. You can barely see it from the outside. There are around 20 people living in about 16 wagons. When we visited Zosch, who is the mayor of the Lohmühle, he invited us for some coffee in front of his wagon.

Jürgen “Zosch” Hans: This was a frontier area in past times between East Berlin and West Berlin. Here was the Wall was going along this area. And this area has not really an owner because the government of East Berlin was not really existent in this time, 1991. So, this government have other things to do than to look after some people who squatted a place. And so, we have the chance to stay on this place. And no police come and took us away. This was changing some years later when there was a district government, and this district government wanted to put us away. But then, it was too late because the people around this area was on our side. They come to our cultural activities, they know us, and they don’t want the district to push us away.

Tomma Suki: Zosch and the inhabitants of the Lohmühle are a good example of how a countercultural ethos has and continues to find a place within the city. But this project began right after the fall of the Berlin Wall at a time when people could take advantage of the political and territorial confusion. Market forces were much less of a factor in determining the viability of radical collectives. Since then, there has been a narrowing of the possibilities for countercultural expression. The merging of Eastern and Western political infrastructures made the Berlin real estate market extremely difficult to navigate for those outside of a corporate structure. Since 1989, there has been a massive privatization and sell-off of public land. In the past three decades, more than 50% of Berlin’s public real estate that is suitable for development has been sold off to private companies. The effects are now becoming apparent on the housing market. It is almost impossible to find an affordable place to stay. The Berlin-based architect and researcher Florine Schüschke researched the facts and figures behind the massive privatization and published an article in “ARCH+,” a German architecture magazine.

Florine Schüschke: The situation in Berlin was special at the time. It was many free spaces and many spaces that were also not regulated so much, which was a quite huge potential for the cultural spaces that emerged everywhere. But there were many interests in the free spaces. The politicians that ruled at the time were from the conservative party, and they wanted to make Berlin a really big metropolis and wanted to do that with the help of private investors because that was the political view at that time. It was a quite neoconservative, or neoliberal, you could also say, attitude that they had at the time. And so, from a city planning perspective, many of these free plots were directly sold to private investors and were developed by private companies. After the fall of the Wall, the city of Berlin sold more than 8,000 plots of land that used to be state-owned. It equals the size of several neighborhoods. It’s 21 square kilometers of land that was sold, and therefore privatized, altogether, which is really a huge amount of land. It is almost half of the plots that the city used to have, if you take out parks and other green areas, but half of the plots that were also suitable for building for development purposes were sold and privatized. So, it was also the housing companies that were sold with the plots, especially in the Eastern part of the city, there used to be a lot of state-owned housing companies, and they were also sold at the same time, so this is how the city of Berlin lost, really, a lot of their social housing. The process was also continued not only in the years directly after the fall of the Wall but also during later years, and then, at the end of the millennium two really big housing companies were also privatized entirely from formerly almost 500,000 social housing units. By now, the city has only 300,000 left because the rest of it was sold and also sold with the plots of land that were privatized. There were several reasons why they privatized land over the years. The first reason, right after the fall of the Wall, was that the dream of a metropolis didn’t really happen because in the ’90s the city was actually shrinking. This was the beginning of quite huge debts that the city got, and these debts were then augmented in 2001 when a big banking crash happened, and the city of Berlin had to take over all the debts from these private banks. So by then, a lot of plots were actually sold because the city always said they had to sell public land in order to pay off these debts that they mounted. You have to really say that this didn’t really work out because what they actually earned from the privatization of these plots was just not very much money in comparison to what they had to spend at the same time.

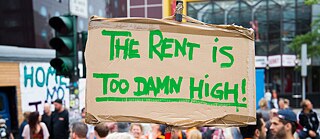

Tomma Suki: When I moved to Berlin seven years ago, it was still possible to find an apartment at a relatively affordable price. But recently, the prices have spiked dramatically, forcing out long-standing communities from their homes, making many low-wage earners commute long distances to their place of work in the unaffordable inner city and discouraging new, poorer members from diverse communities from living near once renowned creative centers. Displacement is no longer limited to hip neighborhoods but happening all over the city. Those who cannot afford to pay do not have a chance to live in what I hope will continue to be the thriving city community of Berlin. The lack of affordable housing is not only a Berlin or German-specific phenomena. In many big cities all over the world, the privatization of community-owned land has created a precarious housing situation for many citizens. Shawn Micallef is a Canadian writer who writes about urban issues and city life for “The Toronto Star.” He spoke with us about the city’s relationship to affordable housing.

Shawn Micallef: The affordable housing story in Toronto is linked with Ontario, our province, and Canada, and it’s a long history. When you walk around Toronto, there’s a lot of public housing buildings, but it’s really interesting that the newest ones all have this like postmodern style to them, which was popular in the late ’80s and early ’90s, which quickly fell out of fashion. But they really stick out because like that’s the last era, the last real era, of building affordable housing and co-ops and these other kind of models and levels of affordable housing. So, the government has really been out of the business of it and allowed the market, the private developers and that sort of thing, to be really the sole creators of public housing. And Toronto, and to an extent Canada, after World War II, had a really, really strong push for building houses. Like there was loads of government supports and programs and, you know, entire suburbs. Postwar suburbs in Toronto, you can just say, this would probably not have happened, you know, if it wasn’t for government programs, but we stopped doing that. And I think in general in Canada, in North America, you know, public housing is seen as like a temporary thing, you know, like for people who have, you know, fallen down the economic rungs, that sort of thing, rather than other places, certain European places, Singapore, I think Hong Kong, you know, where middle class families live in public housing because big cities are expensive, and that’s a totally normal thing. Whereas, that culture doesn’t really exist here. So, these are kind of big historical things that kind of inform how we got to this situation, but the city of Toronto itself, you know, this incredibly wealthy city, one of the most wealthy cities in the world, and yet, it’s not seen as a critical civic value to pay for housing, you know, from the kind of civic and municipal level. We have very low taxes, we just don’t pay for housing. We just don’t. The housing, the shelter system, you know, that first level of emergency, get people off the street, is inadequate, and that inadequacy goes up to more permanent housing and that sort of thing.

Tomma Suki: The current housing crisis has become much more visible as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Capacity was reduced in some shelters to conform with local distancing restrictions. And where capacity was not reduced, many people living in public shelter systems no longer felt safe, as the virus was spreading rapidly in indoor congregant settings, and staff and supply shortages created hazardous, and in some cases, deadly conditions. These factors led to many citizens beginning to live in encampments on public land in Toronto.

Shawn Micallef: So, there’s always been encampments of different kinds in Toronto. I mean, there’s a long history that goes back to the Depression even. And even before the pandemic, especially when the leaves fell in the fall, you would see people living there, and there’d be the occasional tents in a park, but since the pandemic hit, we saw the rise of these much larger encampments. You’d see dozens of tents in some parks, some of the downtown parks, and it was actually one of the first signs of what the pandemic was doing, other than empty streets and that sort of thing at the beginning. Because you saw all these people who said that they were not feeling safe in Toronto’s shelter system, which has always been overburdened. But COVID was spreading in the crowded shelters, so people said that they felt safer being outside, being in the park. And for the first year of the pandemic, it seemed like there was a tolerance of them because, you know, we’re in this emergency, this unprecedented emergency in our lifetime of a global pandemic. And you know, Toronto has had a housing crisis for 20 years now, and we have overcrowded shelters, and I think there was this tolerance of like, yeah, this is a bad time, this is what people are doing to survive. And I live near one of the parks that had encampments — still has encampments actually, it wasn’t cleared out. And there’s a sort of balance generally of kids playing over here and people doing tennis or just having picnics. And here there is encampments, and it all just sort of worked. Encampments were seen by just about everyone, including housing activists, as not being ideal. Nobody wants people to have to live outside. They’d rather have proper shelter and that sort of thing, but during this time, it seemed like it was the workable solution — until a few months ago in June when the City of Toronto started evicting them.

Tomma Suki: In the summer of 2021, the city government of Toronto began evicting people who were living in encampments on public land. When some residents refused to leave, private security contractors and the Toronto police began forcibly, and in some cases violently, removing encampment residents. This triggered protests organized by local residents. Signs declaring, “I support my neighbors in tents: no encampment evictions,” began appearing all over the city. To learn more about the situation within the camps and those who support them, we talked to Aliya Pabani and Allie Graham. They work with the Encampment Support Network, the group that supports the lives of encampment residents and produces the “We Are Not the Virus” podcast. Each episode talks about encampment life and gives residents a chance to communicate their stories and struggles to the public.

Allie Graham: People want different things across the board. Like some people have been so traumatized by the shelter system and by housing workers that they literally do not believe, even when they get a housing offer, that it’s real. And so, there are some people who want to stay outside because they actually do not think that there is another option. So, they would rather not be like taken through the system again and again and have actually just opted out altogether. Some people dream of like moving out to the countryside and having a plot of land and not being bothered ever again. So, there are some people who feel that way, but I think it is always like, in a way, even if someone doesn’t want a permanent apartment that’s rent controlled, the desire is to have a safe space, have autonomy, and to not be harassed. And so sometimes, that looks like an apartment, sometimes that looks like a plot of land. But yeah, there are definitely some people who love to be outside and like more so than the be outside piece, it’s that people love to be in community with each other. And something that’s really challenging for people who have gone from being in an encampment with, say, people they love and trust or like have gotten to know and be in contact with regularly everyday, to go from a context that is so communal and social really is what it is, to say, an isolated hotel room can be really upsetting, can be scary, especially if you’re someone who uses and really relies on community support and people checking in on you, but also it’s very lonely. And so, I think there’s a lot of reasons why people maybe don’t want these housing options, but also, the thing that’s important to say is that the housing options are extremely rare. Like we haven’t met many people who are like, yeah, got offered another apartment, no thank you! It’s like people are not seeing housing workers for months, and some people have never talked to a housing worker ever.

Tomma Suki: When public parks become a place of private shelter in a time of need, difficult questions are raised about the use of common ground and what constitutes the common good. How are the citizens reacting to the difficulties and inequalities created by the privatization of public space? How are they fighting back?

Shawn Micallef: The, you know, the parks have always been seen as truly public space. Last winter, I noticed a sign, on one of the ski hill signs, that was tacked on and it said: private property. And it really just struck me like how bold it was. So, there’s this like kind of like almost gray fuzzy area that, you know, the city even on its website says in a few places, you know: public property is everything owned by the government: the roads, parks, sidewalks, et cetera. But then, like technically, the City of Toronto is a corporation. That’s how, you know, cities are legally, their kind of legal standing in Canadian law, municipal law, is the Corporation of the City of Toronto. And that corporation owns private property, and the private property is the parks, and the parks are governed by all these bylaws: no camping, no structures. And you know, it governs skiing, and it governs swimming and all kinds of stuff. Drinking in the parks, which you can’t do. So, I think that always has existed under the radar of most people because it’s never really been tested. But because the encampments brought it up to such a visible level and when the city was pushing back and pushing them out, they had to lead. They had to give some justification of it. And so, they started putting up these private property signs, you know: This is private property, there are rules. So, it was like I think for people who were sympathetic to the plight of the encampments but also, you know, park users who kind of had this maybe romantic notion of what the public was, what the public realm was, it probably was a bit eye-opening. I mean even like for me it was like, wow, they’re really going hard with the private property thing, which is at odds with so much of the feeling around, public parks are for everyone, we want you to enjoy them and that sort of thing. These two things exist simultaneously, and it’s a strange thing.

Tomma Suki: Resistance and solidarity are important tools within democracy to voice objections and influence political decisions. In Berlin, there is a long tradition of creative resistance. “Who owns Lauratibor” is a protest opera that deals with the selling of the city to private interests. The collective opera project is a form of activism striving for a more equitable civic space. It arose from the cooperation of long-term organized residents and businesses in the area around Reichenberger Straße who are threatened by displacement. [MUSIC] We visited the opera on a Sunday afternoon in June. An improvised stage was built in a public park in the middle of the city district Kreuzberg. We could see around 50 performers running around making last-minute adjustments before the performance began. By the start of the opera, there were around 300 curious neighbors gathered around the stage to watch the performance. At the end of the show, we talked to the director of the opera, Konstanze Schmitt.

Konstanze Schmitt: We are working on this opera since late 2019. The idea came from different projects, which are like involved in the struggle against gentrification in Berlin and between others like housing and artist spaces like LauseBleibt, Lautibor Strasse 10, and Ratibor14, which then like started with the idea that we should like find another form of protest.

[MUSIC]

Performers: Human beings getting verdichtet, like squeezed, getting more and more squeezed in the city, getting more compact, getting more compact. It’s about place you don’t have in town anymore, you know. It was like, Kreuzberg was very famous for its Mischung. This means you worked there where you lived. So, you had all these houses, backyard houses, where there was manufacturing in. And in the front you could live or whatever there, Seitenflügel, yeah. And this opera is because one of these houses like Lause 10, is a house like that still because people are working there and living there, so. But this is not the concept of the market. The concept of the market is to make high-priced apartments for people who don’t even live or work there, yeah. So usually, investors consume operas after their, whatever, deal. And this is an opera we consume to stop them.

[MUSIC]

Tomma Suki: What will housing look like in the future? Will city governments redefine their attitude towards public housing and intervene more strenuously in providing affordable shelter to lower-income residents? Will the trend towards privatization of public space and the displacement of lower-income communities continue, leading to downtowns exclusively populated by the very wealthy, served by those commuting vast distances to serve them? In Berlin and in Toronto, we have talked with people who are actively opposing the current politics of city development. Among local residents, collectives, communes, networks, and weekend opera groups, there is a concerted effort being made to move public discourse and civic policy towards the interests of those being harmed or forgotten by current housing regimes. If they succeed, can society move forward and establish a more community-based approach to shelter? Space is a privilege, and Toronto’s housing crisis will not be resolved overnight, and we will never return to the Berlin of the ’90s. We need to find long-term solutions that can cope with the demands of our time, complex as they are, and find a way to distribute space more fairly.