Next generation: Paula Rosolen

Injecting something Alien into the Dance World

A mane of red curls and an energetic appearance are the first things you notice about the Argentine-born choreographer. Her unusual choreographies move with relish between dance history and popular culture, dealing with musicals, for example, or with the pianists who accompany dance rehearsals. Paula Rosolen, born 1983, has received high-profile funding in recent years. She has been choreographer in residence at the K 3 – Centre for Choreography in Hamburg, has staged a piece with support from the Dance Heritage Fund of the Federal Cultural Foundation and has won first prize in the Danse Élargie competition at the Thêatre de la Ville in Paris with a preview of her new piece “Aerobics!”.

Ms. Rosolen, how did you come to take up dance?

I think it was like any girl taken to ballet by her mother. But my classes were more playful, it was not just a ballet school, but I learned different contemporary dance techniques. After leaving school, I studied choreography and art history in Buenos Aires. It was then that I noticed that dance was more intensive for me, that I enjoyed the challenge. Finally, I went for a dance audition at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Frankfurt and was accepted, actually just to study abroad for one year.

So why did you stay?

When I start something, I like to finish it. After four years, I did not want to go back to Argentina empty-handed. And then the MA in "Choreography and Performance” was set up in Gießen, and I was one of the first four students to be accepted. That gave me the time to develop something of my own, to find out what my interests are.

What did you discover there?

Firstly, the possibility of working with documentary theatre. I got to know the methods of oral history from visiting professor Jeff Friedman; I am very interested in them. In Gießen, how things are done was important. And I had space to develop methods myself, to see how ideas can be implemented, how research can be structured and ideas staged.

For me, interviews are a way of approaching things that are new and unfamiliar and of getting to know them, of obtaining information that is not written down, recollections, movements, voices. How do you describe dance, how do you remember it? After all, dancers often speak in gestures and movements.

What is your artistic approach to the material you have researched?

I take it apart, classify it and then, of course, it depends on the particular project. In Piano Men, I was looking for a narrative because pianists hardly move on the stage. It was exciting to discover the pianists’ perspective of dance, a perspective not otherwise heard. They are people who have spent a long time with a choreographer or teacher, who can describe dance very precisely, that interested me. In Die Farce der Suche, a piece about the dance pioneer Renate Schottelius, I tried to revive her personality from all the finds, documents, and fragments. For me, the way I arrange my material for any particular project is choreographic work.

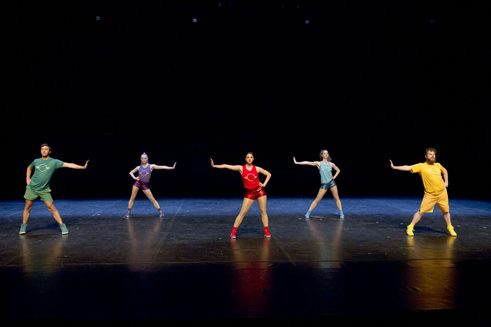

In „Piano Men“ and „Die Farce der Suche“ you have dealt explicitly with dance history. In other pieces you inject something alien into contemporary dance – in „Libretto“ it was the musica and in „Aerobics!“, which you are working on at the moment, it is a training method that became very popular in the 1980s.

What I find particularly exciting is to bring something into the world of dance that does not belong there. I take aerobics apart and dissect it until only the essence is left. I then regard that essence as dance and confront it with questions from the field of theatre, dance and performance, with codes that are not part of aerobics – this confrontation interests me. I have occupied myself with Aerobics! since 2012, but for a long time I was unable to find co-producers for it in Germany – until I received the invitation to come to Paris last year and to stage a miniature version of the piece at the Danse Élargie competition. That enabled me to show it here too. It will finally have its premiere this year, with performances at the Sophiensæle in Berlin, at the Mousonturm in Frankfurt and at the Théâtre des Abbesse in Paris.

Why do you think it was so hard to find co-producers in Germany?

I think people do not believe that everyday knowledge and popular culture can bring something interesting into the dance context.

What are your visions as a newcomer?

I would like to look at issues or areas that many people know already or that are present in the media from a different perspective with my knowledge as a choreographer who knows internal codes, places movement in time and space, and creates rhythm. Piano Men was also about discovering hidden dance. Or rediscovering movements that already exist, that is also archaeological work. As a choreographer, I function as a filter; I am the one who makes the selection.

How do you handle the legacy? How do you set yourself off from the fathers and mothers?

I would not set myself off from anything. It depends on the project and on what I need for it. I like working with larger groups, but that also depends on the context. Libretto has twenty dancers, Piano Men has two. The means and methods used depend to a great extent on the idea and the project in general.

Your ensemble sizes are indeed unusual – many young choreographers primarily work with small formats such as duos and trios. In „Aerobics!“ there are now seven dancers on the stage, including yourself.

As an observer, I noticed that there is this limit, and I asked myself how I could manage financially to work with larger groups. For me, it’s also a kind of statement – I do not want to be forced to work with one to three dancers.