German Indie Games

Board game

Riad Djemili left one of Germany’s top studios to co-develop a digital board game together with a friend. "The Curious Expedition" was a surprise hit. Now there is a sequel.

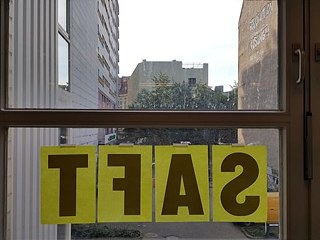

Berlin’s Saftladen is one of the leading addresses for indie games from Germany. The collective was founded by Riad Djemili. It is tucked away in Berlin at the Kottbusser Tor. The grey building is to be found behind a grey gate and a grey parking lot in the midst of a swarm of cafés, snack stalls and congested traffic. Inside about 20 headset-wearing members from various studios sit brooding before their monitors. Chatting is done in English, readily with thick accents.

But the lonesome times with colleague Johannes Kristmann also served to establish Riad. Under their studio name Maschinen-Mensch the duo developed The Curious Expedition (TCE). The title in retro optics is a kind of board game for one person. In the nineteenth century, gamers travel to distant lands and experience all manner of terrors and wonders there. Riad and Johannes built up a fan community over several years and marketed the game very successfully. They are now developing their ideas in a new direction. The current titleonce again relies on procedural contents – in other words on set pieces that the computer recombines in continually new ways. “This time around, you explore characters, not landscapes,” explains Riad. Crime stories set in the Weimar Republic are explored. Riad sees parallels to the present in the interwar period: Disillusionment with politics, escalating extremism, the collapse of democratic systems, coupled with extreme partying, hedonism and drug use. “The game is still in its initial stages. TCE remains the figurehead for now.

5 Questions for Riad

In your view, what makes a game good?

What’s important for me, at least as far as our games are concerned, are interesting, relevant contents with socially critical or cultural references.

Why did you leave a major studio to launch your own very small one?

I was with Yager for seven years and I wouldn’t have stayed there so long if it hadn’t been good. There are many reasons why I left. The most obvious is that we were working full-time on a project with 100 people, and a hundred associate team members all over the world. If you have an idea there, you first have to convince your immediate superior, then his or her superiors, then your colleagues. Development processes and decisions can drag on for months. I found myself gazing enviously at the indie scene, at how fast and un-commercial developers are there. Of course they also have to survive commercially, but the target sums are conspicuously lower.

What inspired you to develop TCE?

To us the expedition theme was relatively fresh and unused. A context in which we could tell lots of stories – especially stories about failure. This was an initial idea: that the gamer fails over and over again, learns over and over again, and enjoys trying yet again in a new way. What fascinated us about real expeditions was that they fail on account of the tiniest mistakes, from the wrong footwear or improperly-stored provisions.

TCE also reveals the dark sides of imperialism. But one has to play for a longer time to discern that. Is it unimportant to you if gamers miss this?

It is not unimportant to us. But it’s a delicate balancing act: we don’t want to moralise. I don’t think that is an efficient tool. We do want to draw gamers to conduct themselves in a specific way. We perhaps don’t know where the gamer is exactly clicking, but we do exercise influence over the game mechanics, making some actions more attractive and others less so. And ideally the gamer then reflects on what he or she has done. That’s important to us.

Very early on in our research we came upon the racism and sexism of the era. And then we considered: is it acceptable at all to deal with this epoch in a game of this kind? We concluded that it is if we approach it right.

Do game developers have a responsibility to society?

As with all art forms, game development is also free to be socially relevant or not, as the case may be. Pop music also has a reason for existing. But our personal aspiration is not to make pop music. We find ourselves instead in a more ambitious artistic niche. I want to have the feeling of doing something meaningful with my life and my abilities. My medium is the computer game. I therefore think about how I can create a cultural reference with computer games so that I can express something about how I see the world. And I wish more developers would have this aspiration; I would like to see more politically-charged games.