Biennales and Urban Development

Myth or Reality?

For some years now, art biennales have been viewed as the “blockbusters” of the art industry, drawing thousands of visitors. Are biennales promoting urban gentrification or are they contributing to a steady urban development adapted to community conditions?

Five years after Kathrin Rhomberg, curator of the 6th Berlin Biennale, had been reviled as a “gentrifier” and her photo plastered onto the main entrance of the biennale at Oranienplatz 17 in Berlin-Kreuzberg – stronghold of the squatters’ and protest movements – the building is undergoing renovation. Sheer happenstance or a logical consequence of the biennale?

It was no coincidence that the 13th Istanbul Biennale of 2013, held at the same time as the protests concerning the preservation of Gezi Park, was entangled in a debate on urban development. Above and beyond street protests, the biennale opened up a discursive space for political engagement and civic movements in which the transformation of public spaces was also negotiated.

The linkage of art and urban development is not a new topic. In recent years public administrations have been making use of biennales to upgrade their cities, but also for “city branding,” to market them. In addition, biennales promote local identity, visibility and international competitive positioning.

Above all in poorer residential quarters, the improvement in housing through cultural facilities or increased cultural offerings can result in displacement of entire population groups. They are in turn replaced by other groups of people described as “creative, young and cosmopolitan.” Whereas some consider it a neighbourhood “development”, for others it does not necessarily mean progress.

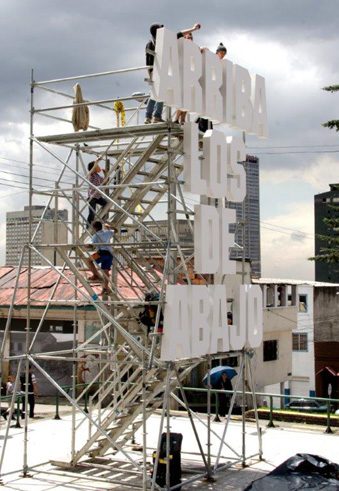

“Arriba los de abajo” – upgrading communities

By contrast, La Otra Bienal (i.e. The Other Biennale) in Bogotá can be considered an example of successful adjustment to local conditions. Starting in 2013 as an independent event, it used to be an alternative art fair that run parallel to ARTBO since 2007.One of its goals is to strengthen the community of residents among each other. With this aim, La Otra Bienal focuses on the location of the event and its complexities. Its first edition was devoted to the theme of “fronteras invisibles”, invisible boundaries. It illustrated the social, historical and cultural tensions of three urban neighbourhoods that all lie very close to each other, but are radically different: the upmarket residential neighbourhood Bosque Izquierdo; La Macarena, known as “Bogotá’s SoHo” currently undergoing an obvious process of gentrification; and La Perseverancia, a former workers’ quarter which nowadays is considered particularly dangerous.

“The real estate bubble is a fact in Bogotá, as well as gentrification processes”, confirms Emilio Tarazona, one of the four curators. “The contact with these urban scenes does not trigger gentrification, neither does prevent it. In any case, it enables us to take a more critical and attentive look at this process”, states Tarazona. An example is the fotonovela Gentrificación no es un nombre de señora (i.e. Gentrification is not a Woman’s Name), which arose as part of a biennale workshop.

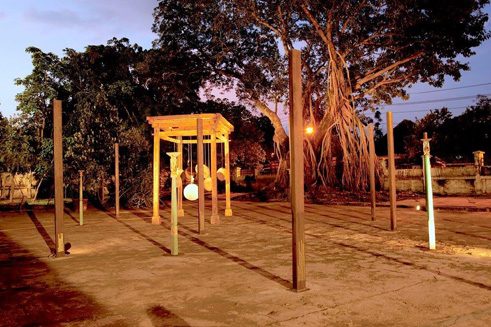

Welcome to the Biennale City

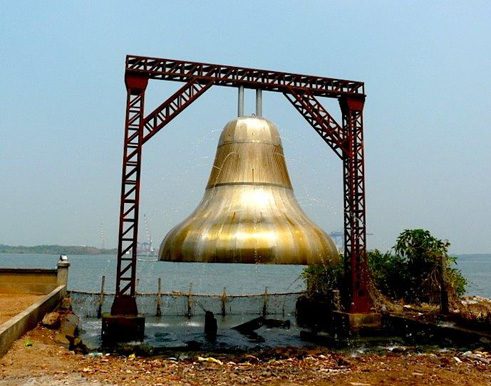

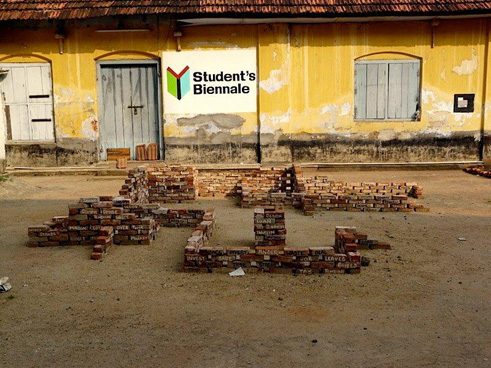

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale was launched in 2012. Since then, Kochi, southern India’s most important harbour city, has served as a backdrop for contemporary art. The biennale’s founders developed a concept that captures the attention of both the local as well as the international public. Its themes are wide-ranging: alongside works by internationally recognised artists, there are works by young Indian art students. Parallel to this, as “Collateral Projects”, further events such as video programmes, lectures, residencies and a diverse programme for children and young people are held scattered over the entire city.The biennale has activated or refurbished new spaces for art: former warehouses (“godowns”), wharfs and factory buildings are filled with art. Visitors to the city are welcomed with a banner reading “Welcome to the Biennale City”, which also pleases residents as the biennale generates income for them as well. The federal government of Kerala, which has been supporting the event since its establishment, is also very much aware of this.

“The Kochi-Muziris Biennale celebrates both contemporary art as well as the cultural legacy and history of the city,” explains Abhayan Varghese, the Biennale’s Director of Communications, which is why the city preserves its own rhythm after the event is over and no one is displaced.

Generating visibility and attention

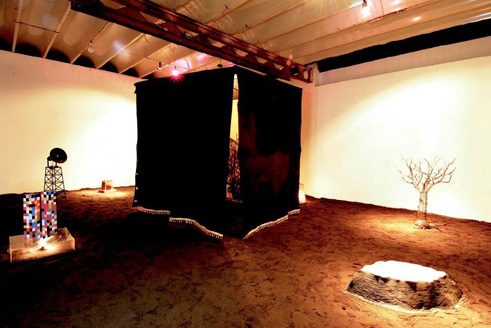

In 2011, the Biennale Jogja Equator was founded in Yogyakarta, one of the most important spots for contemporary art in Indonesia apart from Jakarta and Bandung. For political and cultural reasons, the initiators decided on a coalition of equatorial regions to enter into a South-South dialogue for a period of ten years, from 2011 until 2021, and thereby awaken interest in new art locations. For each edition, a country or region is invited to cooperate with the local Indonesian artists’ community.“Hacking Conflict” is this year’s theme between Indonesia and Nigeria. As yet the biennale has received only little support from the local city administration, although it is also gradually recognising the significance of art as a means for the city’s development and for tourism purposes.

While in some places art biennials are conceived as “external” city marketing strategies that take scant account of the needs of local communities, they are perceived elsewhere as projects that promote integration in urban development through art, that might enhance local art scenes’ profiles and position them on the international market. It is also clear that they have become an economic factor that cannot be ignored. Whether they will be able to create cultural and material added value for local conditions and urban development, as well as remain sustainable, must be determined on a case-by-case basis.