Edgar Leciejewski’s bildarchive

Of Windows and Frames II

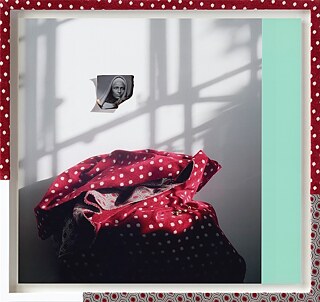

Talking about the prolific use of windows throughout art history, let’s keep looking from the inside out and the outside in and see how the digital world changes our gaze. After investigating Leipzig photographer Edgar Leciejewski’s “dashes” out of his studio window, the first photo here takes us inside his studio—including the shadows his windows throw onto his interior Polaroid display.

By Jutta Brendemuhl

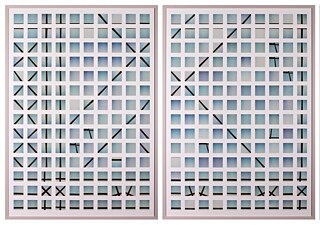

Frames and windows give form and direction to artworks, hold visual information, add three-dimensionality to a two-dimensional medium, just as the strict rules of the sonnet or haiku give guidance and shape to words to allow expressive freedom. “The photographers place us in an interior, making it possible for us to share with the artists the intimacy of their daily view,” Getty Museum photo curator Karen Hellman comments on the shot from the inside out. Czech photographer Josef Sudek’s The Window of my Studio series is an exquisite example from art history. Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich created the masterpiece Woman at a Window (viewable in augmented reality), whose gaze Hellman follows: “Portrayed from behind and framed symmetrically by the window, the female figure serves as a stand-in for the viewer, while she in turn looks out on the landscape beyond. The window, then, offers the link from interior to exterior, from the inner perspective of the artist to the world outside.”

Online though, will we go (or have we gone) beyond the window, post-Internet? Decades ago, Susan Sontag had already disabused us of a simplistic equation of photography and “frames” pointing towards the crucial distinction between reality and artistic traces. In her book of essays Where the Stress Falls, she says: “Photographs are not windows which supply a transparent view of the world as it is, or more exactly, as it was. Photography gives evidence—often spurious, always incomplete—in support of dominant ideologies and existing social arrangements. They fabricate and confirm these myths and arrangements.”

The squareness and amateur invitation of Instagram still seem to lend itself to window formats—The World For Now is a collective quarantine art project by Munich’s Su Steinmassl that collects follower photos, guided by a quote by Persian mystic Rumi: “If the house of the world is dark, love will find a way to create windows.”

Next time, an interview with Leciejewski about digital and analog living and working in this moment in time.