30 Years of German Unity

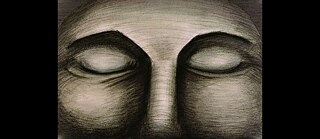

Lutz Dammbeck, avant-garde artist in the GDR

Lutz Dammbeck is one of many artists who turned their back on the German Democratic Republic (GDR) before the Fall of the Wall. What made him leave?

By Karin Oehlenschläger

Lutz Dammbeck, born in 1948 in former East Germany, began working as an artist in the early 1970s when he developed "media collages" based on experimental films and conceptual photo series. In the 1980s, these were among the most interesting works of art in the GDR, and, seen from today's perspective, his work was also significant beyond the small country’s borders. It was with this unique artistic approach that he began creating his multimedia work, Herakles project, which was his most important asset when he moved to Hamburg, West Germany in 1986. He is still developing this project to this day.

In Dammbeck’s memory, the GDR was gray, dead, and colorless, and in the 1980s the mood in the country became increasingly depressing. As early as 1968 when the Prague Spring was crushed and a period of political liberalization and mass protest in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic ended, Dammbeck realized that this was foreshadowing the end of the (leftist) system. Artists' festivals, the semi-legal occupation of a trade fair building for the 1st Leipzig Autumn Salon (1984), and activities within the network of like-minded friends between Leipzig, East Berlin, Karl-Marx-Stadt and Dresden brought a little color and variety. However, it didn’t last.Formally, the reason for his application for departure (Ausreiseantrag) was the rejection of his 10th application for a study trip to the Federal Republic of Germany. It was the consequence of a discussion that had been going on for many years: "to leave or to stay", the same question his parents had been asking themselves since before the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961. When the authorities finally rejected an important project after many years of negotiating back and forth, he had had enough and decided it’s time for a new beginning.

Since 1986 Dammbeck has been living with his family in Hamburg. The decision to immigrate to Hamburg happened by chance. In 1985 Dammbeck and his wife, a photographer, had applied for an exit visa. The Stasi (secret police) assumed that a joint exhibition at the Leipzig gallery "Eigen+Art" would be used to provocatively "force them to leave the country." While this notion only existed in the paranoia of the officials, the family was ordered to leave the GDR within 48 hours. This came as a surprise because for months the official response was "you'll never get out of here!" They had two telephone numbers in West Germany; in Cologne, nobody answered the phone, in Hamburg the call went through. The next day they arrived in Hamburg-Altona at dawn.

Is there German unity today? Lutz Dammbeck is skeptical. Since 1945 and the rebuilding of West Germany after World War II, under Allied occupation, Nazi influence in every aspect of society was to be eliminated. In Dammbeck's opinion, what the former East Germans lack is more than 40 years of this re-education—the so-called “Vergangenheitsbewältigung” or "working through the past—and they still have a lot of catching up to do.

When asked what is “GDR culture,” Dammbeck says he’s not sure. Maybe it’s just art that happened to be created in the GDR? He says that remnants of a "German" culture survived longer and more persistently in the GDR than it did in West Germany. But he considers most of what was produced in the East not really the stuff for art museums, but rather belonging in museums of local history, folklore, and archives documenting social affairs. “But only time will tell”, he laughs.