The Pine Ridge Reservation is a place of scarcity, but also the heart of the Oglala Lakota’s cultural identity. People here are fighting fo the future of their memories, traditions and shared values.

It is early morning, the sun barely grazes over the light brown landscape of the prairie. From every direction, the wind carries the tingling songs of meadowlarks. In old tales, their chants are reminders of the beauty of life. The surging roar of a nearing vehicle can be heard from afar, even over the grassy knolls. The sound of a city seems unimaginable.The street leads to Pine Ridge, reservation of the Oglala Sioux tribe in South Dakota. Sioux is a spelling with colonial roots, derived from the French way to write snake or enemy. It carries a decades old fear and prejudice. The people of Pine Ridge prefer Lakota, yet Sioux is used officially. The story of the inhabitants' names is similar: They were anglicised by Euro-Americans, abridged, some altered completely. Spotted Elk for example was a reputable “Grandfather”, chief of his clan. American soldiers mocked him as Big Foot, he presumably had a clubfoot. At the Wounded Knee Creek, on December 29, 1890, he and another 300 defenseless people were gunned down by the 7th Cavalry Regiment. Today, a street is named after him: “Big Foot Memorial Highway, in honor of all chiefs”, a battered road sign tells us - Spotted Elk is not mentioned, and neither is his name in his mother tongue, Uŋpȟáŋ Glešká.

Bigfood Memorial Highway sign | © Tatjana Brode

The site of the massacre is now a cemetery and memorial, located on a hill, with the long rectangle of the mass grave at its center. Above the arched entrance gate is a Christian cross; in front of it, an unpaved parking lot. In its tragic notoriety, this is likely the most well-known site among tourists visiting the reservation, which in turn has made it a popular spot for a kind of roadside commerce. Small tours about the history or handmade dreamcatchers are offered for sale whenever a stranger’s car stops. Here, culture and art are part of the struggle for survival — one of the few sources of income. Most residents of Pine Ridge live below the poverty line: 60 percent unemployment, poor medical care, and widespread addiction. The average life expectancy for men is less than 50 years.

Meet me at Whiteclay

At the southern end of the reservation, just across the border to Nebraska, lies a place that, until 2018, was a focal point: Whiteclay, back then counting 12 inhabitants and 4 liquor stores with millions in revenue. The Lakota Rez police were powerless across the county border, the nearest police station in Nebraska was 25 miles away. “Meet me at Whiteclay” was seen as a kind of invitation to a duel in an almost lawless space. In 2017, after massive protests by the Lakota for years, the liquor stores' licenses were revoked. Today, there are two stores providing groceries and necessities, a restaurant and an art space. The place that was characterized by grief and tragedy has transformed into a site of hope and resilience, promising a better future.

House for artists by Holly Albers and Evans Flammond in Whiteclay | © Tatjana Brode

A sales gallery attached to the Makerspace offers works by Lakota artists, where first-hand direct sales replace the concept of kitschy Wild West stores with “Native Art” from all parts of the country. Groups of students are booked in for workshops, an occasion for which Holly cooks. The project also includes artist residencies, music and theater performances in the summer, and an extension is currently under construction. Far more specific things are needed, donations are welcome to help artists and craftspeople make a living. Holly's aim: “To become a place where tourists come to buy art directly from the artist and talk to the artist themselves to learn about our art and our culture. To be a place for artists to learn from each other. And last but not least for it to be a symbol of what we are as Lakota people – art, spiritual and deeply connected to nature”.

Traditions and Identity

Back at Wounded Knee. Memories overlap; the name also represents the fight for the rights of Indigenous people in the USA. Roughly 80 years after the massacre, in the spring of 1973, students of the American Indian Movement (AIM) and their supporters squatted the area to draw attention to discrimination, inequality and other social wrongs. During the 71-day Wounded Knee Occupation, there were confrontations with the FBI and the U.S. National Guard, resulting in the deaths of two people. Due to national and international media coverage, the concerns of the activists entered public awareness. In the years that followed, Indigenous identity was able to cast off some of its shackles and grow stronger.

Memorial and cemetery at Wounded Knee | © Tatjana Brode

Gardening in the Steppe

Following the Big Foot Trail north from Wounded Knee Creek, you arrive in Kyle, Phežúta ȟaká – Branched Medicine – with just under 1,000 residents. In 2023, the Oyate Teca Project’s Community Center opened here. The Lakota compare their traditional communities to a wolf pack – at the center are children and elders, protected and supported by the stronger members. This principle of radical solidarity guides the project, which primarily supports children and youth through sports programs, cooking classes, and gardening. The area is considered a food desert; fresh fruits and vegetables are scarce. “It was a long road to the opening,” says Dave, who works here. “We do everything we can to strengthen the community.” The young people learn how to provide for themselves, how to remain rooted in their community, and how to survive.

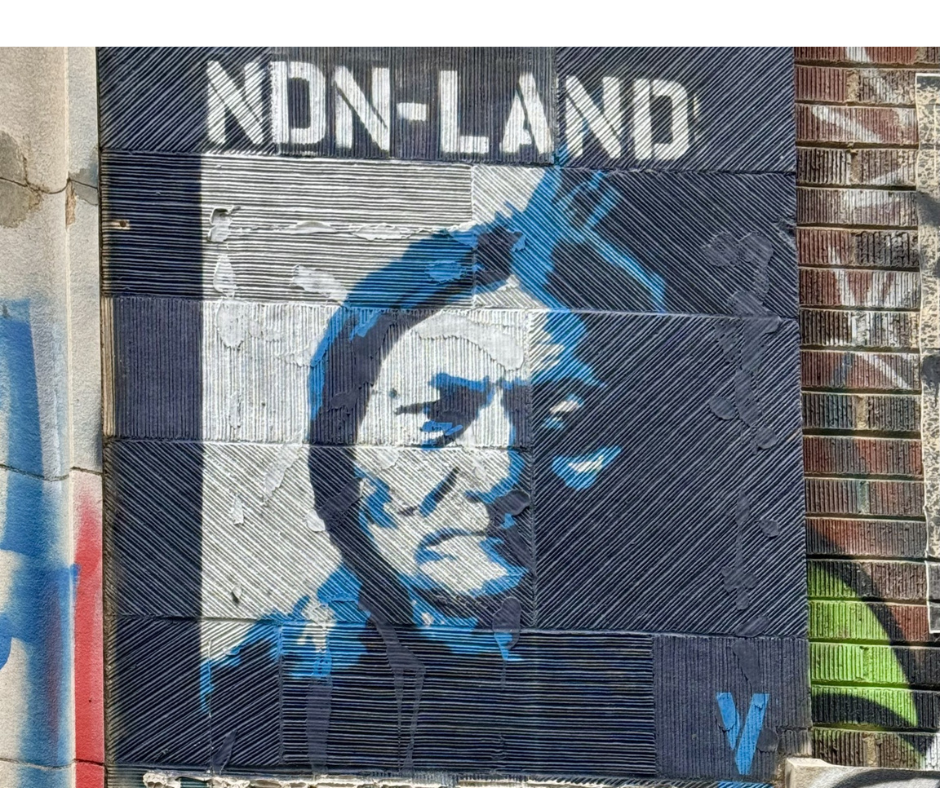

Graffiti in Pine Ridge by John Trudeu | © Tatjana Brode

Evening settles over Rapid City, a Western town 70 miles from Pine Ridge Reservation. Along the main street, the ‘Prairie Edge’ store sells Lakota art and provides supplies to artists. Parked in front is a police car decorated with Native-style horse drawings and the text “Dedicated to the People, Traditions and Diversity of our City”. A police officer is in the process of arresting a Lakota man. He fastens the handcuffs behind his back, pats down the backpack. “I didn’t stab anyone”, the man protests, “I just didn’t wrap up my liquor bottle”. “Hey, three meals and a free doctor’s visit in jail aren’t so bad”, replies the officer. History is not over.

This text was inspired and enriched by the stories of Kathryn, with whom the author wandered through the Pine Ridge Reservation. Thank you.