From 1940 to 1945, Mann appealed directly to the German public in a series of anti-Nazi radio addresses, "Deutsche Hörer!" (Listen, Germany!), brought about through the work of his daughter, BBC journalist Erika Mann. In moving philosophical counternarratives, Mann wages a war on the airwaves against Hitler, Goebbels, and the Nazis — in his own “German” voice — “the voice of a friend.”

The Coming Victory of Democracy.

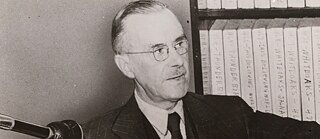

In his lectures “On the German Republic” (1922) and “An Appeal to Reason” (1930), the author Thomas Mann (1875–1955) established himself as an avowed opponent of the Nazis, whom he outraged with his defiant republicanism. Shortly after the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933, Mann again enraged fascists with an ideologically provocative Munich lecture on Richard Wagner, and resigned from the Prussian Academy of Arts, rather than declare his loyalty to the fascist regime. In November, upon learning of his impending arrest, Mann went into exile in Küsnacht near Zürich, Switzerland. By December, the Nazis had expropriated his house in Munich. In early 1937, Mann published a scathing response to the complicitous Dean of University of Bonn for rescinding his honorary doctorate, and then “An Exchange of Letters” on Germany’s descent into “barbarism.” Beginning in 1938, he wrote from Princeton, New Jersey and in 1942 from the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles. By 1945 he had undertaken five tours of the U.S and Canada and delivered over 150 anti-fascist lectures with titles such as “The Coming Victory of Democracy.”The voice of a friend.

From 1940 to 1945, Mann appealed directly to the German public in a series of anti-Nazi radio addresses, Deutsche Hörer! (Listen, Germany!), brought about through the efforts of his daughter, BBC journalist Erika Mann. In moving philosophical counternarratives, Mann defends the right to human dignity and declares war on the propaganda campaigns of Goebbels, and on the lawlessness, lies, mass murder, and war crimes of the “genocidal moron” Hitler, in his own “German” voice––“the voice of a friend.” Mann’s rebuttals provide political news on the Allied nations, comment on the progress of the war, contrast fascism with democracy, measure Hitler against Roosevelt, and answer German propaganda with international consensus. After initially encouraging the Germans to resist their tyrants in tones ranging from sympathy toward German suffering to outrage at the German obedience and political paralysis that made Hitler’s crimes against humanity possible, Mann transitions to preparing Germans for the consequences of defeat and for atonement, while seeking to encourage hope for future reconciliation with the community of nations.

No informed public

From the beginning, Mann’s addresses denounce the Nazis’ inhuman delight in tactics of displacement, deportation, enslavement, conquest, and their increasing violence toward Jewish Europeans. In the address of September 1941, Mann exposes the frivolity of the Nazis’ expansionist program: “Out of Paris [...] we will make the amusement park, out of France in general the bordello and the vegetable garden of German-Europe.” Assaults on human dignity include the dismantling of institutions of culture and education. In August 1942, Mann cites the closure of institutions of learning and research in ‘Czechoslovakia’ as evidence of Hitler’s aim to reduce Europe to “a nullified, neutered, spiritually diminished tool of monopolistic Germany,” devoid of potential future leaders. No informed public, as he explains on 15 January 1943, would fail to see that Nazism’s promise to restore all Germany to a former glory served any goal more than “the self-enrichment of the fat cats, the transformation of the Nazi Party into a colossal economic enterprise, as bloated as Göring himself.”

How bitter it is the defeat

Mann praises as models those who loved peace and liberty more than life itself while delivering withering assaults on Hitler. On 27 June 1943, he pays tribute to the “glorious” University of Munich students Hans and Sophie Scholl, who along with several co-conspirators were executed for spreading anti-fascist flyers. On 28 March 1943, he comments ironically on Hitler’s decline, evident in his increasingly short yet nonetheless incoherent speeches, peppered with alternative facts: “Without fail, his prolific intellect always had so many excellent, wise, and constructive thoughts to convey [...] that any less time would not suffice. [...] Did he want to ‘provide evidence,’ as they now say in Germany instead of ‘prove,’ that mental defectiveness can be revealed just as well in fifteen minutes as in ninety?” Incensed by the Nazis’ ceaseless lying, Mann erupts in March 1944: “This unmitigated malevolence, this revolting, stomach-turning swindle, this filthy desecration of word and thought, this supersized sadistic murderousness toward the truth [...] must be obliterated at all costs and by all means [...].” On 19 April 1945, he eulogized Franklin D. Roosevelt, comparing the wise and eloquent leader with the “abysmally evil and abysmally stupid” Hitler. Yet, when the defeat of Germany he had championed arrived, Mann states honestly on 10 May 1945: “How bitter it is when the defeat, the deepest humiliation of one’s country results in the jubilation of the entire world!”

I say, despite all, it is an exalted hour: the return of Germany to humanity.