Many Lebanese have emigrated during various periods due to economic and political circumstances that pushed them to seek a safe haven away from ongoing conflicts and the specter of poverty. Some dream of returning, but the majority know this option is difficult to implement currently because of the crises the country is experiencing. Is there something that connects Lebanese to their homeland without abandoning the new lives they have built overseas? Hanan Hamdan explores the role of non-governmental associations in connecting Lebanese emigrants to their homeland.

Lebanon has seen successive waves of emigration throughout its history. No official, verified figures on the number of emigrants have been published, but between 2016 and 2024, approximately 640,000 citizens emigrated from Lebanon, according to Information International, an independent Lebanese statistics firm. Lebanon’s current population is estimated at around five million.Having emigrated at various times, some Lebanese expatriates dream of returning, but most know that this option would be hard to turn into a reality, due to the crises afflicting the country.

Josiane Abi Tayeh, 22, left her hometown of Zahlé (eastern Lebanon) for France in 2004. She says, “I loved living in Lebanon, but fate brought me here. I got a job, and I wanted to live that experience.”

From Zahlé to France: The Longing for Home

Josiane lost her father at the age of four, during the civil war (1975-1990). She was born and raised in a five-person household in her hometown of Zahlé, before moving to Beirut to pursue her university studies. Immediately after graduating, she moved to live and work in France.

Josiane recalls her memories of her homeland—“the first home,” as expatriates like to call it. She says, “I miss the warmth of family, the traditions of the city, and the spirit of Zahlé life, which is unlike any other.” On her refusal to return home from France, she says, “I want to ensure a stable and safe environment for my children.

That’s what we currently lack in Lebanon, but we are working to achieve it.”

The relationship between expatriates and their homeland has always existed in Lebanese society, but it has grown significantly due to the successive crises that have buffeted the country. In the past, this relationship was mainly focused on providing relief, humanitarian, and social services, but it has evolved, to the point where expatriates have established associations and groups that are involved in public affairs.

This was the reason that led Abi Tayeh to found “Club Zahlé France,” as a platform connecting denizens of Zahlé who live in France and strengthening their bonds with their home city. “Through the club, we have revived the customs and traditions of our city. As the crises in Lebanon have worsened, the club has transformed into a support framework, through humanitarian initiatives, such as securing diesel fuel for 100 families during the winter,” she says.

Like many Lebanese, Josiane strongly identifies with her homeland, and always returns to Lebanon twice a year with her children, who consider Lebanon an integral part of their identity.

Successive Crises and Migration

Since late 2019, the Lebanese have been experiencing the consequences of the worst economic and financial crisis the country has ever experienced, including the collapse of the local currency, a sharp decline in salaries, and the decimation of savings in the country’s banks, which has prompted an uptick in the number of emigrants, particularly among young people. This was followed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Beirut Port explosion of August 4, 2020, and finally the Israeli war on Lebanon (from September 23-November 27, 2024).These back-to-back crises have given the Lebanese diaspora an incentive to do more to support Lebanon, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have often played an important role in this regard.

“Zaha” Cares for Expatriates from Zahlé

One prominent group is “Zaha,” a non-governmental organization (NGO) linked to the city’s diaspora. It was founded in 2018 at the initiative of the former mayor of Zahlé, Asaad Zgheib.“We wanted to reconnect the Zahlé diaspora with the city, and we sought to institutionalize this relationship and create institutional depth for it through the Zaha Association,” says the association’s president Amin Issa. He adds: “Since its inception, we’ve successfully urged expatriates to maintain this connection. We’ve served as a link between the diaspora and the local community in Zahlé, both individuals and civil society organizations, particularly in providing humanitarian aid to the city’s most needy residents following the crisis in 2019.”

Amin Issa | ©Private

The association works in cooperation with expatriates from the city to provide financial and in-kind assistance, food, and medicine to groups residing in the city. Expatriates also take part in various areas—cultural, social, and economic. Zaha has encouraged expatriates to help restore old houses, in keeping with standards that preserve the city’s architectural heritage, and to create recreational spaces for children in public parks.

Zahlé, known as the “Bride of the Bekaa” after the valley in which it lies, is the hometown of tens of thousands of expatriates who are now spread across the world, including in Canada, the United States, Australia, Brazil, France, and many other places. Many return regularly for short visits.

In addition to improving the living conditions of residents, Zaha encourages expatriates to carry out investment projects in the city and develop productive and tourism projects to reduce youth emigration. To ensure effective communication among expatriates themselves, it has played a significant role in expanding communication, by holding three diaspora conferences. These events brought together individuals and representatives of civil society organizations in Zahlé, as well as expatriates, to familiarize them with the city’s situation and its needs, as well as with how it has persevered and survived through cooperation between residents and expatriates.

Another Model: “Kulluna Irada”

Another example of how to connect and engage the Lebanese diaspora with their homeland is the model of “Kulluna Irada,” an NGO founded in 2017 and committed to social, economic, and political reform in Lebanon. Carole Abi Jaoude, the organization’s Political Networking Director, says it works “to define the foundations of a modern, sustainable, and just state.” The organization “is funded by affiliate members, Lebanese residents and expatriates, who want to help Lebanon and bring about positive change,” she adds.A New Electoral Law

Most NGOs and expatriate groups, with their diverse interests, are active on the Parliamentary Election Law No. 44 of 2017, which is a key political issue due to the voting mechanism for Lebanese expatriates, which will apply to elections scheduled for 2026. The law stipulates the allocation of six parliamentary seats to non-residents, divided equally among the six main sects: Sunni, Shiite, Druze, Maronite, Catholic, and Orthodox, wherever they may be in the world. However, expatriates insist they should have the right to vote on all the seats in parliament, as was the case in the previous elections in 2022.

An Advocacy “Monasarah” Campaign

Expatriate associations and groups have launched an advocacy campaign for the right of expatriates to vote on every seat in the parliament. In this context, expatriate groups have formulated a draft law, already adopted by more than 65 members of the Lebanese parliament, which aims to “consolidate the Lebanese expatriate’s connection to their homeland and strengthen their participation in national decision-making, to preserve Lebanon’s supreme interest and consolidate the unity of the Lebanese people inside and outside Lebanon.”It is worth noting that expatriate turnout in the 2022 elections was at around 63%, out of some 225,000 registered voters, constituting around seven percent of the total number of voters. They have become an influential bloc capable of influencing election results, especially since the number of non-residents has increased in recent years as a result of successive crises that have hit Lebanon.

Remittances sent by expatriates to their families in Lebanon amount to approximately $6 billion annually, which reflects the impact they have in improving the well-being of individuals in their communities, and demonstrates that they remain a fundamental component of it.

Expatriate Groups in the United States

One organization founded in the midst of the popular movements that began on October 17, 2019, is the Lebanese Diaspora Movement. “The movement was formed to organize the Lebanese diaspora’s transformative work and help the Lebanese community abroad shape its political and social vision, especially in light of the many events that Lebanon has undergone,” says Abbas Al Haj Ahmad, a Lebanese university professor and journalist currently living in Dearborn, Michigan. One of the founders of this movement, he adds: “We’re fed up with the poor intellectual and cultural reality in Lebanon, and that’s why this movement was formed.”

Abbas Al Haj Ahmad | © private

Through the movement, expatriates are also active in political and social activism in the U.S., including on municipal and state elections. The movement also cooperates with the World Lebanese Cultural Union (WLCU) and with U.S.-based members of the Lebanese Student Association (LSA) on issues affecting the diaspora. Members of the movement, including intellectuals, students, and many others, also visit Lebanon regularly.

Deprived of Nationality

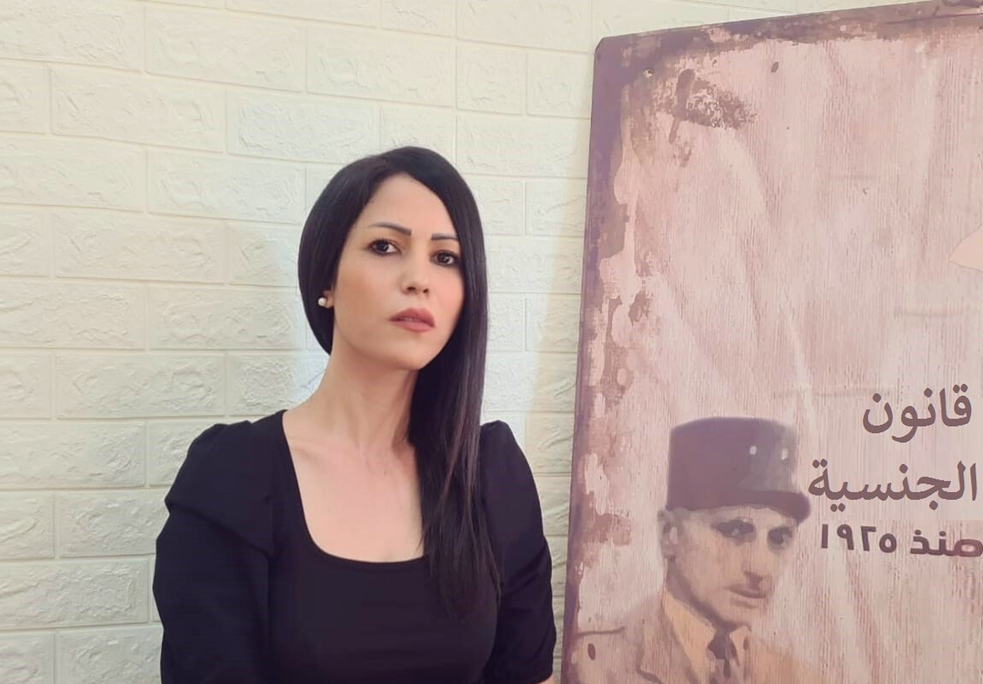

Also living in diaspora countries are individuals born to Lebanese mothers and foreign fathers, and who chose to emigrate as a result of their mothers being denied the right to pass on Lebanese citizenship to their children. In recent years, the Lebanese have been divided between those who support and those who oppose granting citizenship to the children of Lebanese women. Many Lebanese have fought to amend the Lebanese Nationality Law of 1925 and recognize the mother’s right to pass on her nationality. A campaign under the slogan “My Nationality is a Right for Me and My Family” has spent more than two decades striving to raise awareness around the issue.“Our goal is to achieve justice and equality between male and female citizens, nothing more,” says campaign director Karima Chebbo. She adds that the current law is “discriminatory, and inconsistent with international agreements and conventions, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—as well as the Lebanese Constitution, which explicitly affirms equality between all citizens, male and female, without discrimination or preference.”

The principle of a “blood bond” in Lebanon perpetuates gender discrimination, as nationality can only be acquired through the parents. Article 1 of the law states that “Any person born to a Lebanese father is considered Lebanese.” Conversely, Chebbo believes that “the blood bond is the inheritance that any child acquires through the formation of genes determined by the blood of both the mother and the father, and which the child inherits from both their parents—not just the father. In other words, it is an inherent right shared by the mother and father.” Accordingly, she concludes, the blood bond “should not be an excuse to prevent a mother from passing on her nationality to her children, but rather must be the proof of its transmission.”

“My mother is Lebanese and my father is foreign”

Fawzi, who preferred not to give his full name, was born to a Lebanese mother, but says he has been treated as a foreigner and denied full civil and social rights. “I was born and raised in Lebanon. I have memories and details of my life there, and throughout 18 years of my life, I didn’t know any other country,” the 28-year-old says.Fawzi’s mother is Lebanese and his father is Turkish. For the past nine years, he has lived in Italy, where he originally moved on a university scholarship. He majored in chemical engineering, and currently works for a company there.

He describes his feelings toward Lebanon, especially in light of recent events: “In truth, my sense of belonging to my country, Lebanon, is strong and is growing with time, despite the distance. Today, I feel more attached to it, and would love to return.” He continues: “I feel sad about the painful things Lebanon has experienced recently. I follow the news, and I feel helpless, because I can’t change it.”

He adds: “If I had Lebanese citizenship, I would have voted without hesitation in all the elections, including the parliamentary elections, to help bring about change. The issue of expatriate voting and political participation is hugely important, but unfortunately, we’re still marginalized.” He concludes: “I don’t know what they are waiting for to grant us Lebanese citizenship. It’s our mothers’ natural right, and I believe this is the most unjust form of deprivation, for both mothers and children.”

Ultimately, the factors that have driven Lebanese people to emigrate have evolved over time. Despite their insistence on communicating and connecting with fellow citizens, whether through NGOs and expatriate groups, or individually, their dream remains that their country, mired in political, economic, and social crises, recovers and becomes a safe haven for all its citizens, both residents and expatriates, should they decide to return.

August 2025