As a distinct ethnic group with their own language, culture, and indigenous to the region, Assyrians maintain a unique cultural identity, despite displacement and emigration. While many Assyrians have formed diaspora communities abroad, particularly in North America and Europe, a significant population still lives in their ancestral homeland. Through her poignant family history, Alfreda Eilo recounts what it means to hold on to one's heritage and to be part of a marginalized group in the diaspora, weaving intergenerational sentiments from and into the homeland.

I remember it so well. I woke up early one morning in November 2023, rolled over in bed to check my phone for news, a daily ritual of mine that I unfortunately share with many inhabitants of Beirut, but this morning was painfully different. I looked down and immediately recognized a face I did not expect to see on social media or the news. Confusion and grief washed over me as I processed that this familiar face belonged to my ḥōlō (granduncle in Syriac), Gevrieh Ego from our village of ʼAnḥel in Tur Abdin in Southeastern Turkey. He was 94 years old. This is how I found out about the assassination of my ḥōlō, a beloved Assyrian elder in his community - via an Instagram post.

Instagram Post: Death Announcement of Gevrieh Ego | ©Instagram assyriansolidarity

As Assyrians, we have been witnessing the slow and steady destruction of our community that continues in the present, evidenced most tragically in the politically motivated assassination of my ḥōlō in Turkey. The indescribable pain of having a relative assassinated was followed by the realization that my ancient village ʼAnḥel, home to generations of my family dating back hundreds of years, has been completely emptied of its Assyrian inhabitants.

Alfredas great-grandparents tombstone in Anhel, Turkey | ©Private

Assassinated for Testifying

ʼAnḥel cannot be found on the map. To trace it, one needs to google its Turkish name Yemişli to even find it on maps. Me and my family, as indigenous Assyrians from what is today’s Turkey and Syria, have lost yet another link to our homeland. My ḥōlō Gevrieh was murdered over a land dispute between Assyrian families and Kurdish tribes. As the elder of the village, he was asked to give testimony in a local court to testify to his knowledge as to the ownership of disputed lands. My ḥōlō Gevrieh lived in ʼAnḥel for 94 years and knew every person who entered and left our small village of ʼAnḥel. Neighboring Kurdish tribesmen — likely motivated by my ḥōlō’s testimony in a land dispute— murdered him outside his home.Such conflicts between Assyrians and their Kurdish/Turkish neighbors are widespread in Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, well-documented by human rights groups. Like settler violence in the West Bank, these groups exploit Assyrians’ marginalized status — targeted for their distinct language, culture, and religion. Land disputes stemming from unlawful squatting and seizure of Assyrian homes and villages are par for the course and further threaten the diversity and history of these regions.

Revisiting the ‘athro’ (homeland)

Alfredas grandmother Peyruze with her older brother Gevrieh infront of their house in Anhel | ©Private

Teta Peyruze at Mor Kyriakos Church in Anhel | ©Private

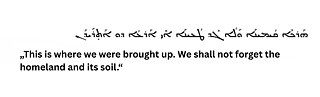

One vivid memory from that trip was visiting Mor Kyriakos Church in ʼAnḥel, where three generations of women in my family were baptized in a small stone basin. I filmed us walking out as the custodian locked the gates. It is unsafe to leave the gates to the church estate open; we are not welcome in our own homelands. My grandmother muttered, “This is where we were brought up. We shall not forget the homeland and its soil.” It was an offhand remark; one she repeated whenever faced with injustice. The weight of her words resonates now more than ever.

A typical Assyrian daughter in the diaspora

I was born in Switzerland, a typical Assyrian daughter in the diaspora. I was never brought up in our lands, surrounded by the sacred soil, maintained by the ancestors. Instead, I grew up like any other immigrant child, in a constant dance around my identity. The sense of always feeling incomplete developed into a rebellion against my identity and a resistance towards our traditions and culture. This rebellious resistance later developed into an insatiable curiosity into my existence, my history, my heritage and my hybrid identity both as western-raised and as part of an ancient indigenous people in SWANA. This curiosity for my identity yielded into various travels to our homelands in Turkey and Syria, insisting on learning both Turkish and Arabic, a form of discovering more about my own native language, Syriac. Eventually, my journey of discovering my Assyrian self, led to my adventurous move to Beirut, Lebanon. A city close enough to my own ancestral homeland, yet less enjoyable for a young, unmarried Assyrian woman in SWANA. I love my homeland, but as a woman raised in the West, I've grown accustomed to freedoms I couldn't have there, and so a life in our ancestral villages would be hard — so hard it might taint my love for who I am and where I’m from.From self-discovery to advocacy

My journey of self-discovery and acknowledgement of my indigeneity continues. I’ve become an advocate not just for my own people but for all Indigenous communities in SWANA, deepening my understanding of diaspora identity and cross-cultural solidarity. Moments of transnational activism — especially calls to end Palestine’s genocide — have marked milestones in my path, connecting me to a community of Indigenous advocates fighting for collective liberation. It was through my Palestine advocacy — posting Instagram videos without overthinking consequences - that I found a community of Assyrian diaspora activists representing an inclusive and diverse collective of young people with politically nuanced views.What emerged from it is the Assyrian Movement for Collective Liberation, a group of Assyrians spread throughout the diaspora, with roots in Syria, Iraq, Turkey, Lebanon, and Iran, working together and amplifying our demands and those of other Indigenous communities for justice and liberation.

When I recently called my grandmother after nearly a year away — unable to return to Switzerland due to Israel’s war on Lebanon — we spoke about ḥōlō Gevrieh, our people’s struggles, their parallels to the Palestinian struggle against colonisation and oppression, and the fractured identity in the diaspora. Surprisingly, she admitted that despite loving her life in Switzerland and the hardships that drove her from Tur Abdin under Turkey’s oppression, she always felt like an outsider. This feeling of not being complete or not fully belonging to the diaspora will stay with her until the end of her life. Her words, echoing what she’d said in Tur Abdin, weighed heavily on me. I, too, may always feel incomplete — whether in the diaspora or in the homelands, forever foreign. Yet this very absence fuels my drive for justice and reminds me that identity is shaped in the pursuit of it.

About Assyrians

The Assyrian community has endured severe displacement and violence, particularly during the late Ottoman period. The Hamidian massacres (1894-1897) and the 1909 Adana pogroms-initially targeting Armenians but also affecting Assyrians, drove many refugees to the U.S.

The Assyrian Genocide (Sayfo, 1915-1916), occurring alongside the Armenian Genocide, devastated the community, killing an estimated 275,000 Assyrians and displacing countless others. French monk Jacques Rhétor documented catastrophic losses: 86% of Chaldean Catholics, 57% of Syriac Orthodox, 48% of Syriac Protestants, and 18% of Syriac Catholics were killed or disappeared. The genocide involved mass executions, abductions, sexual violence, death marches to the Syrian desert, public humiliation and the destruction of cultural and religious heritage, permanently altering the region's demographics and shattering Assyrian political and cultural unity. Its traumatic legacy persists today.

Related Links

August 2025