The war in Sudan has been ongoing since 2023. For Sudanese people with disabilities, it has transformed structural exclusion into an existential threat. Rahma Mustafa reports on the suffering of people with disabilities, but above all on their resilience and initiative amidst the continuing violence.

Sudan’s war has lasted for two-and-a-half years, wreaking devastation across cities and displacement routes while deepening a crisis long in the making. For Sudanese persons with disabilities, the war has transformed structural exclusion into an existential threat. Homes have been destroyed, hospitals emptied, and entire neighborhoods trapped without safe passage. Some who could not flee have reportedly been executed. Others remain stranded in inaccessible shelters, their lives hinging on the presence of a ramp, a wheelchair, or a neighbor who can lift them to safety.Yet amid the collapse of state systems and the paralysis of formal humanitarian responses, something else is happening—something powerful, defiant, and deeply rooted in a rights-based vision of equity. Sudanese disability advocates, many displaced themselves, are stepping into the gaps with a clarity of purpose that is reshaping communities from within. They are not waiting to be rescued. They are organizing, educating, negotiating, and building solutions where none exist.

This is their story—of survival, yes, but also of leadership. Of communities that refuse to be erased. Of civil society writing the first draft of an inclusive future in real time.

When Exclusion Becomes Life or Death

For people with disabilities in Sudan, exclusion did not begin with the war. “The suffering of persons with disabilities did not start on April 15,” says activist Anas Alzubair. “It is a long story of marginalization and the absence of basic rights.”Before the conflict, many schools lacked ramps; clinics were few and inconsistent; and assistive devices were unaffordable for luxuries. Stigma, not support, shaped public perception.

But war has turned these pre-existing inequities into lethal barriers. Gisma, a woman with visual disability now living in Port Sudan, describes how quickly normal life evaporated: “The war did not start our suffering—it only multiplied it. Before, survival was difficult. Now it feels like a privilege.”

Throughout Sudan, testimonies reveal how inaccessible infrastructure has become a silent killer. In crowded shelters, wheelchair users cannot reach latrines; blind individuals lack guides to distribution points; and deaf communities miss evacuation alerts because no sign-language interpreters are present.

Mariam, a wheelchair user who lost her home early in the fight, recalls the night she fled: “I cannot move safely around the camp. Every noise feels like a threat. I cannot sleep. I feel completely unsafe.”

With hospitals destroyed or occupied, rehabilitation services have nearly collapsed. Assistive devices—wheelchairs, crutches, hearing aid batteries—are almost impossible to replace. Meanwhile, explosive weapons continue to create new disabilities daily. Burn injuries, traumatic amputations, and spinal injuries have surged, especially among children.

As fighting escalates—particularly around Al-Fasher in North Darfur—the consequences are brutal. According to multiple humanitarian organizations, including Humanity & Inclusion (HI), some persons with disabilities have been unable to flee and were reportedly executed in their homes. Others remain trapped as hospitals collapse, and supply routes close.

Vincent Dalonneau, HI’s Country Director for Sudan, reported: “This wave of violence is unbearable, and it particularly affects the most vulnerable people, especially those with disabilities.”

War is not just creating new disabilities through explosive weapons; it is also stripping up the systems that once allowed people to survive. Without rehabilitation, war injuries become lifelong impairments. Without protection, disability becomes a marker of extreme vulnerability.

But in the vacuum left behind, disability civil society has stepped forward—and begun rebuilding from the ground up.

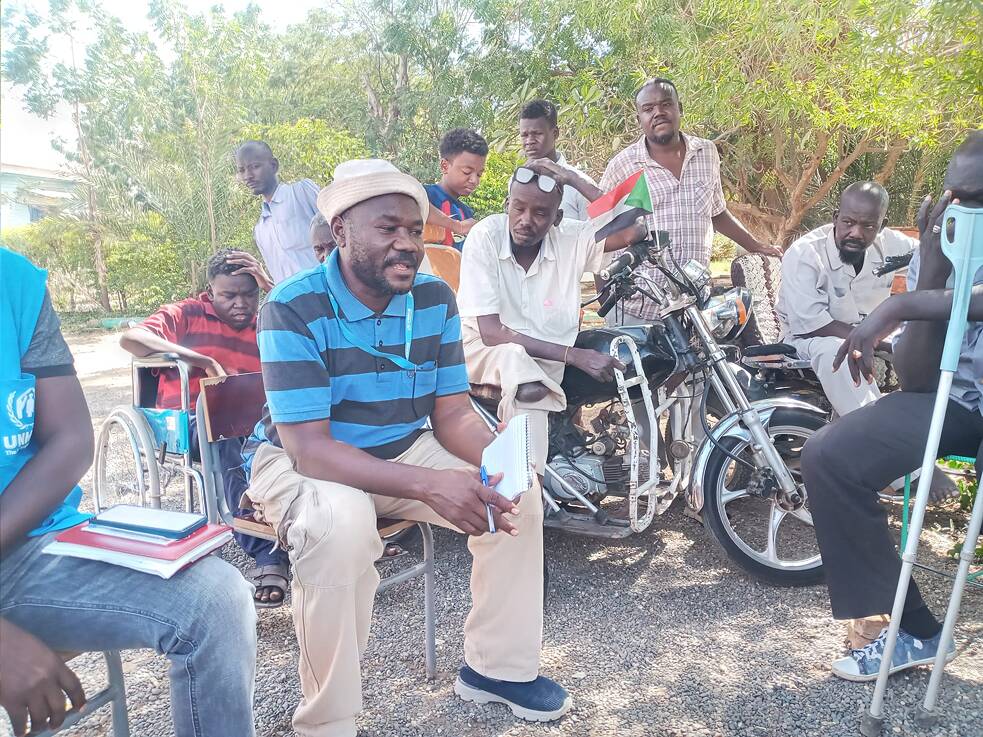

Grassroots Leadership to save lives

Amid devastation, Sudan’s disability movement has emerged as a powerful engine of civil society. Advocates—many displaced themselves—have built support systems faster and more effectively than formal structures.WhatsApp and Facebook have become the backbone of community-led humanitarian efforts. Networks like Safe Passages (Mamarrat Aamina – آمنة ممرات) coordinate evacuations, share real-time security alerts, locate missing persons, and arrange accessible transportation for people with disabilities.

Nabil, a volunteer in Gadarif, explains: “We mapped every person with a disability in our camp. Then we negotiated with aid groups for accessible toilets and ramps. We organized ourselves before anyone else did.”

These networks do more than save lives—they restore dignity. They translate alerts into sign language, record audio for people who are blind, and provide simplified guidance for those with intellectual disabilities. Beyond emergencies, they establish central kitchens, adapt camp environments, connect people to services, run training programs, and celebrate the International Day of Persons with Disabilities. Where formal systems falter, these networks fill gaps with ingenuity, care, and inclusivity.

A Historic Victory of Inclusive Exams in Cairo

In exile, Sudan’s disability advocates achieved a milestone few thought possible. When families fled to Egypt, students with disabilities risked losing their academic future—until parents, teachers, and activists organized the first-ever external sitting of the Sudanese Certificate Exams in Cairo. “This was a huge battle—we refused to let the war steal their future,” says Hayfaa, a special educator. With accessible exam centers, sign-language interpreters, psychosocial support, and official approval, the community rebuilt an inclusive system in the middle of displacement. As one teacher put it, “They did everything possible—and some of the impossible.” For the diaspora, it proved that even in war, rights can still be defended.Disability, Gender, and Survival

Women with disabilities, often among the most marginalized, have emerged as some of the most influential leaders.Weam, a prominent activist, recounts why her coalition stepped in to distribute menstrual health kits to displaced women: “During war, nobody brings these supplies to displaced women with disabilities unless we raise our voices.”

Her group collaborated with mainstream feminist organizations to distribute menstrual hygiene kits, reproductive-health supplies, and dignity packages to hundreds of women in displacement camps.

Women activists have also shaped national-level advocacy. In coordination with the social development sector and UN Women, they contributed to a developing strategy for the economic and social inclusion of women with disabilities—one of the few forward-looking policy efforts launched during the war.

“We urgently need realistic and sustainable planning to reduce the harm faced by women with disabilities,” Weam emphasized.

Policy Wins: When Advocacy Translates into Reform

Despite the chaos, Sudanese OPDs (Organizations of Persons with Disabilities) have driven meaningful policy changes.1. Restoring Identity and Access to Aid

Many displaced people lost their national IDs while fleeing. Without documentation, they were denied cash assistance. OPDs petitioned the Ministry of Interior for an exemption—and won. The Civil Registry waived all fees for reissuing identity documents for people with disabilities.

2. Ending Discriminatory Banking Requirements

Previously, persons with disabilities were required to bring a “guardian” to open a bank account. After sustained advocacy, the Central Bank abolished this rule, ensuring equal access to financial services.

3. Strategic Partnerships for Aid Inclusion

Local OPDs forged alliances with the International Organization for Migration, Sudanese Red Crescent, and women-led groups. Together, they registered persons with disabilities in shelters, ensured accessible aid distribution, documented rights violations, and advocated for safe, inclusive evacuation routes.

These wins reflect a core truth: inclusion is achievable when those living the reality shape the solutions.

Community and Grassroots Interventions

Across Sudan and the diaspora, disability-led networks have created micro-systems of care that reach far beyond formal aid. Volunteers used simple spreadsheets to track new arrivals and ensure no one was excluded from assistance. Teachers ran informal learning circles to support children with disabilities who lost their years of schooling. Activists created accessible information channels that reached far beyond formal announcements. Mothers formed support networks to share food, medication, and emotional care.One mother summarizes this spirit: “We fought for a seat at the table and showed that disability is not defeat—it is strength and will.”

What an Inclusive Future Requires

Sudanese disability advocates are already modeling what inclusive recovery should look like. Their practical proposals form a clear roadmap—one grounded in rights, not charity:1. Full Participation Persons with disabilities must be represented in all decision-making bodies—from camp councils to national reconstruction forums.

2. Barrier Removal Physical accessibility must be guaranteed for shelters, clinics, and latrines. Communication, too: emergency info must be available in sign language, Braille, and simple language.

3. Gender-Responsive Support Programs must respond to the specific needs of women and girls with disabilities, including sexual and reproductive health, protection, and leadership.

4. Direct Funding for OPDs Grassroots disability organizations are often first responders in crisis. Donors must invest in their capacity and sustainability.

5. Inclusive Data Systems Disaggregated data (by disability) ensures visibility, accountability, and better-targeted aid. Local, community-led registration is essential.

6. Narrative Change People with disabilities are more than victims. As Mona, a prominent disability activist, put it: “Our hope is to be seen as leaders, not burdens.”

Those Who Refuse to Be Left Behind

Sudan faces catastrophic violence, yet its disability community is leading with extraordinary courage. Their message is clear: inclusion is not a luxury—it is a human right, even in war.True resilience, they show, is not endurance but transformation; not waiting, but leading; not hope without action, but action that creates hope. As a disability leader in Kassala said: “We organize, we educate, and we care for each other. That is how resilience is born.”

Sudan’s reconstruction must be guided by those already building inclusion in the shadows of conflict. The global humanitarian community, governments, and donors must follow their lead: fund their work, amplify their voices, and commit to systemic change. Those hardest hits deserve more than survival—they deserve partnership and a voice in shaping their own future.

February 2026