Like others, Palestinians experienced adverse social and psychological consequences of Covid-19 pandemic, and the prolonged lockdown which started in Palestine in March 2020, just like other countries. During lockdown people experienced fear, anxiety, isolation and stigmas, the outcome of Covid-19 amid the lack of psychological counselling and concentrating on the physical medication of Covid-19 patients. During this chaotic period, special personal initiatives highlighting the importance of psychological counselling and demanding that attention be paid to it, emerged.

A year and a half ago, Nuha Salama felt that she was not well; she was not getting along well with herself and her inner side. She had not the power to stand any part of her life. She continuously cried for three months and was getting moody and constantly feeling tired, gripped by a feeling of capitulation, rejecting life outright. Her burden was compounded by the presence of a daughter in need of diligent care and attention, as her husband was working far from home. Her condition was complicated by Covid-19 and the lack of communication with the world around her.Nuha knocked the walls of the tank[i], and communicated with Hanan via Facebook. “Our acquaintance was the best experience I ever had”, Nuha says.

Hanan Walid, is a psychology specialist and counselor, living in the old city of Ramallah in Palestine. She works at a clinic within a comprehensive medical centre, where she receives her patients and psychological counselling seekers. Her job is delicate and sensitive; she is engrossed all day in listening to the concerns of children and adults, their problems and sensitive feelings, offering them a safe space to talk, play or practise specific behaviours.

Child Salam arrives at the clinic. A child showing both innocence and manhood. He complains about his mother’s dubbing him a “liar” when hiding doing his homework from her. Before that self-disclosure session, he asked Hanan to play with him “the ladder and snake” game. He plays while expressing his love of the green colour. Hanan carefully and wisely listens to his speech, which made the child speak so openly in her presence without fear, hesitation, or shyness. Like others, Palestinians experienced adverse social and psychological consequences of Covid-19 pandemic, and the prolonged lockdown which started in Palestine in March 2020, just like other countries. During lockdown people experienced fear, anxiety, isolation and stigmas, the outcome of Covid-19 amid the lack of psychological counselling and concentrating on the physical medication of Covid-19 patients.

During this chaotic period, special personal initiatives highlighting the importance of psychological counselling and demanding that attention be paid to it, emerged. The first of these initiatives came from psychiatrist, Hanan Walid, to be followed some time later, by that of the psychologist Salah Malaisha.

Hanan lost at the time facial contact with her patients, and, given the uncertainty as to what may happen the next day, matters got more complicated on a daily basis.

Hanan volunteers

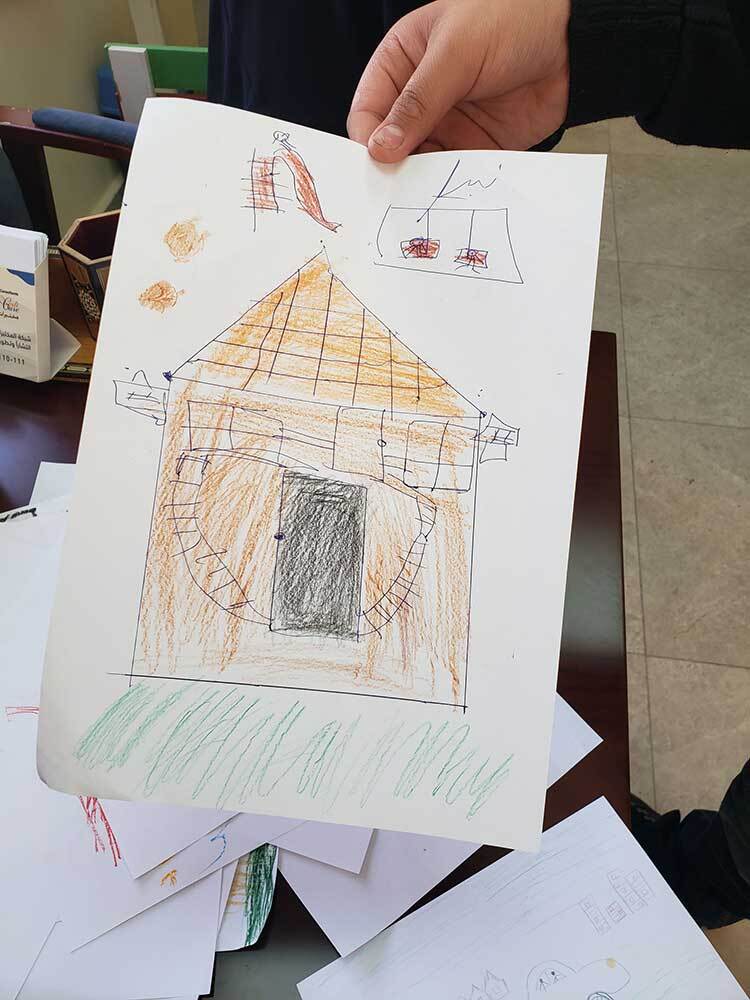

Encouraged by her friends, psychologist Hanan Walid, launched her volunteering initiative in psychological counselling via Facebook. “I several times posted [on Facebook] that I’m ready to volunteer, whether as part of an organized team or individually”, Hanan Says.At her clinic, Hanan normally deals with children belonging to the age group (4-18) where she offers them therapeutic sessions and counselling for their parents.

However, her initiative opened the door wide for cases like that of Nuha and the others. Hanan says: “declaring the state of emergency was so sudden. Like others, I had to stop working and seeing my patients all of a sudden. Therefore, I tried to find a way for communication to check on them. We were not sure of anything. How long will the lockdown last before beating the virus? We didn’t know. It was necessary to follow up with my patients, especially that psychological effects seemed to accompany the lockdown. For example, the anxiousness of an anxious child increased. Also, some behaviours surfaced, which parents couldn’t cope with, like the stubbornness of children, rejection, anxiety, or depression”.

That was what triggered her initiative. Then things took a different turn after some children contracted Covid. She then opened her initiative for older people. She says: “I was ready to offer help, things started to develop gradually”. However, she encountered several obstacles.

Disorganized Psychological Support Teams

Hanan says:” I waited for psychological support to get more organized by intervention teams and crews from competent bodies’, but the emergency state prevailed in many aspects, as our country was dominated by a state of mess and uncertainty for the future”.“Normally, in emergency cases, intervention is manifested on the ground. However, this didn’t work with Covid. The priority of medical intervention was given to patients suffering from Covi[ii]d-19 physical symptoms. It didn’t help to intervene as psychological specialists. It seems we had to wait a bit. Then I got in touch with people who recovered from the virus, or who were on the road to recovery. I also resumed following up with patients who started to suffer from a “stigma” because of contracting the virus”.

She goes on to say: “It’s so unfortunate, especially for those who first got infected with the virus. Many feared them. This restricted their normal return to work. None received them in their houses even after they had recovered. Communication with them was essential to get rid of the “stigma” notion”.

Hanan managed to psychologically help in these cases. However, later on, cases started to increase and the fear became more medical than psychological. She even lost communication with cases she is taking care of because one of the family members contracted the virus. She says: “Everybody had the priority of being provided with medication; nevertheless, I remained on alert.”

“I have been volunteering from the start of lockdown till now. There are individuals facing difficulty returning to normal life, as events are unpredictable. This case applies to some teenagers who refused to return to life and preferred to communicate from afar. Therefore, my initiative is still ongoing”. She also encouraged children to return to school, Hanan says: “in general, children found that staying at home is easier for them. It is as if the world was facing a threat, without expressly saying that, added to that their feeling of loneliness; no one will come to their aid if they were in danger”.

“Any patient experiencing psychological symptoms because of the pandemic has their own specificity”, she adds.

After undergoing online psychological self-disclosure sessions with Hanan, Nuha describes her case as follows: “If you saw my pictures before, you’d find me a different person now. Hanan offered me a secure space to talk and vent during sessions held weekly. She constantly took my feelings into consideration, and provided me with recommendations for raising my daughter in case matters got complicated. She doesn’t see us as people paying her money in return. I feel that dealing with my family and feelings today became seamless”.

Salah Malaisha - Another Unrecognized Hero

Although psychological specialists declined providing support during the pandemic, Salah Malaisha, the psychological specialist and counsellor, was trying to support Hanan. Salah works in some establishments and volunteers in others. He studied societal psychology in Birzeit University. He says that the origins of his volunteering in providing psychological support during the pandemic date back to war times in Gaza Strip since 2014 and the presence of patients from Gaza in the hospitals of the West Bank for treatment.Salah, who descends from Jaba’ town in the district of Jenin, northern West Bank, says during the pandemic: “I used to help people maintain their calm and how to enjoy a good mental health inside their homes especially after we learnt of many problematic issues within Palestinian families between children and their parents, or between couples”.

According to his plan, psychological support services were distributed over various aspects, despite its “randomness” as he describes it, he sought help from the Palestinian Counselling Centre and from mental health experts. Then he expanded the range of his volunteering beyond his town, Jaba’ and his city, Jenin, northern West Bank, reaching Nablus in the centre.

In his workplace “Palestinian Counselling Centre”, Salah tried to provide support by responding to telephone calls and answering the questions and queries of those in need. He also circulated his mobile phone number via social media to anyone in need of consultation or support. He says: “psychological counselling was based on moving afterwards to individual sessions”.

Salah speaks about the idea of telephone counselling: “It is a training product carried out by mental health specialists; it collates previous experiences of remote servicing, as well as experiments of specialists who worked during wartimes in the West Bank and Gaza. A training material was collected; I arranged and formed it using different ways for others to be able to benefit from. It is a realistic and responsive material for adult counselling specifically”.

Challenges to their volunteering

Represented by the Ministry of Health, the predominant tendency of the Palestinian government was to secure beds, oxygen, and hospitals for patients. The Ministry of Education, in turn, tried to recruit school social counsellors to provide remote psychological support. That was reckoned a “weak point” by Hanan, saying: “we didn’t practise enough to respond to the pandemic”.Although the teams of the Ministry of Health were trained to provide psychological support, this, however, “came late” according to Hanan. The Ministry of Education “tried to bridge the students’ academic gap without paying attention to the psychological gap. Sport, art and other extracurricular activities classes were cancelled. They didn’t try self-disclosure with students; consequently, there were many referrals to private clinics”.

Salah and Hanan faced huge challenges during their volunteering; the most prominent challenge being the “randomness of work”. Hanan says: “our work was disorganized during lockdown, after the gradual easing of the state of emergency, mental health clinics and centres started to receive a high number of cases in need of help”.

During lockdown, Hanan provided psychological support and counselling for around 20 individuals based on her knowledge and experience. Precautionary and medical guidance for Covid-19 patients prevailed on psychological counselling. She explains that by saying: “the individuals used to talk about their feelings and the help they needed, their concerns, feeling of guilt, fear or death premonitions. It was important to contain their feelings and guide them to new therapeutic behaviours. In addition to children’s nightmares, which I tried to treat by providing them with playful and breathing activities and encouraging adults to play with them”.

These cases increased after the return to face-to-face learning and schools taking to refer their students to psychological and behavioural counselling centres. Hanan Says: “I started to meet around 10 students suffering from behavioural problems every week”. “Given the uncertainty, lack of vaccines and recurrent lockdowns during the state of emergency and economic pressure, stress, anxiety and psychological disorders increased. Also, familial disintegration increased, especially in cities. Despite some relief, Salah says: “There are still cases in need of psychological counselling because they are experiencing real problems in communication. The pandemic shock is still having its toll on Palestinians.”

An Initiative Without an end line

Up till now, Hanan continues her initiative single-handedly. “To a specialist this is a dangerous indicator”, she says.“ It is better to have a counsellor or a supervisor in time of crisis to support and guide us, added to that the advantages of collective work”, she adds.I was not embraced by any framework or institution, which annoyed me. I really wanted to be part of a team. No one wanted to join my initiative, either. Maybe they felt afraid and uncertain. In addition to the differences of opinions in providing medication for patients first then psychological support. In spite of that, this support was not organized in a specific framework till now”.

With regards to assessing her initiative, she smiled a little and said: “maybe I rushed into launching it. Maybe I should have waited a bit, but I didn’t want to be late in providing support. I am happy with my experience during the pandemic. It showed me the human nature in time of crises”.

Hanan and Salah volunteered in the absence of a ready national and comprehensive mental health team in Palestine.

Salah says: “We are in need of volunteering teams and prepared establishments in every governorate. We also need to officially organize disorganized support and to reward volunteers”. He says in disappointment: “No official body appreciated the efforts of mental health volunteers during the pandemic, nor did anyone thank them for that”.

Child Salam returned home having finished the self-disclosure session in Hanan’s clinic, pumped with confidence in his ability to finish his homework and making his mother feel proud of him. As a child and schoolboy, Salam is not able to discern this large and complicated world; however, with her initiative, Hanan is able to pave the way before Salam and others so they can understand the world and embrace it.

[i] A reference to the three Palestinians who died in the water tank while being smuggled from Iraq to Kuwait when no one of them dared to knock on the walls of the tank for fear of being discovered i.e. they lacked the power and courage to do that. (note by translator).

April 2022