Krautrock

The rehabilitation of a genre

Krautrock, long appreciated only abroad, is at last finding appreciation in its native Germany as a groundbreaking chapter in pop music history.

It was once a term of abuse. Krautrock. Back in the late 1960s, when the genre emerged that would go down in the history of pop music under this name, none of the relevant musicians wanted to be identified as a krautrocker. “Krauts” were what the British called Germans, and the name was not meant nicely. It resonated with memories of Nazi, Second World War, bombs on England.

Problematic relationship to krautrock

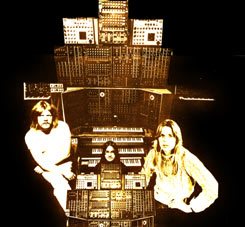

That the German relationship to krautrock is a problematic one has historical reasons. The term was coined by the British music press and subsumed pretty much all rock and pop music that came out of Germany from the late sixties to the late seventies, when punk rock changed everything. It made no difference to pop critics whether Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream produced electronic music for discotheques, Can oriented itself to the latest work of avant-garde composers, Kraan played jazz-rock with endless solos, Agitation Free adapted the psychedelic rock of the American West Coast or Birth Control wanted simply to rock as hard as they could: if it came out of Germany, then it could only be krautrock.But the term krautrock was felt to be derogatory not only because the main figures didn’t particularly like being lumped together with other bands in whom they saw no musical similarities whatever; the expression also expressed the Anglo-American disdain for the pop music of backward Germany. As most of these bands, dissociating themselves from the contaminated past of the German pop tradition and the mainstream of British and American rock music, quite deliberately developed their own musical ideas, and at a high level of performance, they were particularly wounded by this contempt and felt it confirmed their inferiority complex. The Hamburg band Faust responded to this with irony and recorded the twelve-minute track Krautrock.

First rethinking in Great Britain

This reception changed significantly only in 1996 when Krautrocksampler was published. The book by Julian Cope, himself a successful musicians, bore the subtitle “One Head’s Guide to the Great Kosmische Musik” and, in spite of many technical errors (due to which the author has declined to reissue the work), radically changed the perception of krautrock. Since Cope’s equally subjective and compelling history lesson appeared, krautrockers are no longer regarded as epigones but rather as musicians who, in seeking to satisfy Anglo-American standards, created something new, namely “cosmic music”.Cope recognised a quality that, at least in retrospect, is common to the otherwise so different krautrock bands. Whether they created ethereal electronic worlds like Kraftwerk, lost themselves in endless improvisations like Amon Düül or explored the fascination of monotony with trance-like rhythms like Can: many krautrockers created experimental, hitherto unheard sounds with a spiritual force that often seemed unreal and dreamlike, as if not of this world – as if, that is, they came out of the cosmos.

From term of abuse to seal of quality

It is above all this quality that ensures Radiohead covers pieces by Can and Neu!, young British bands like The Horrors and Kasabin reveal themselves to be krautrock fans and that in 2010 the English newspaper Guardian judged krautrock to be the “pop influence du jour”. The heroes of the past such as Eloy go on tours again and young German bands such as Von Spar, Stabil Elite and Space Debris consider themselves to be decisively influenced by the old recordings. That more and more of the often vanished recordings of the past are being reissued and rediscovered is owing to small, dedicated labels like Bureau B and Grönland. But a major player such as Universal has also re-released albums by Embryo, Harmonia and Jane, which were issued in the seventies by the legendary label Brain.