Dance

Dance Life Festival

By Abigail Arunga

Artzone | Dance| Transeo © Jay Ndikwe

Artzone | Dance| Transeo © Jay Ndikwe

“Dance and sing to your music. Embrace your blessings. Make today worth remembering.”—Steve Maraboli

Dancing, as a symbol of expression in itself, has long been a stalwart fixture in the business of humanity; whether you’re doing it badly or well, for competition, for celebration, in your house, alone in your room, to seduce, to entice, or to live. This is something that Adam Chienjo, the curator of the Dance Life Festival, in conjunction with Goethe-Institut, understands all too well.

The Dance Life Festival was conceptualised by Goethe Institut and Adam Chienjo during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. While other artists still had a few opportunities during the pandemic—visual artists still sold work, musicians had live gigs that were streamed online—the dance scene hit rock bottom. The idea to counteract this was the first Dance Life Festival, through the livestreaming of eight performances and ten dance classes.

Dance in Kenya has generally not been very visible over the past few years. There are basically no supporting structures and no opportunities for dancers to show their more conceptual work. Therefore, the festival was also to serve as an annual platform that showcases the diversity and quality of dance in Nairobi. From traditional to contemporary, via ballet, afrofusion, urban, seben, raga, and tap dance—the festival shows the vibrant dance scene that still exists, despite all the challenges.

Adam Chienjo, curator of the Dance Life Festival © Ray Ndikwe

The tireless efforts and ideas of Adam Chienjo led to the production of four dance films that were screened at the second edition in 2021. The event was further expanded through a collaborative piece between the Ugandan choreographer Catherine Nakawesa and the Nairobi-based group Empire Dance Kenya, which was the closing performance of the festival.

Adam Chienjo, curator of the Dance Life Festival © Ray Ndikwe

The tireless efforts and ideas of Adam Chienjo led to the production of four dance films that were screened at the second edition in 2021. The event was further expanded through a collaborative piece between the Ugandan choreographer Catherine Nakawesa and the Nairobi-based group Empire Dance Kenya, which was the closing performance of the festival.

“My role is to find the art in the dancers, and give it some guidance. I’m here to make it make sense, and try to achieve a balance in the genres of dance. I ensure all kinds of representation, from genres, to genders, to backgrounds. That is my role as the curator of the Dance Life Festival,” explains Adam.

When Adam initially pitched it to Goethe-Institut, the idea was to unpack the dance scene in Nairobi as well. “A lot of dance things happen in Nairobi, and everyone has their own version of what dance in this city is. With this festival, I can do the work of linking dancers to other dancers, dancers to other choreographers, dancers to dance festivals, and dancers to audiences.” This is still true even in a pandemic, where the festival took place virtually. “I am really just trying to set people up artistically and for the main performance. I want to have what, in my view, is a good representation of dance, but also in a way that can improve dance in Kenya, and how people see it, and have an opportunity to consume dance as an art form in a professional manner.”

This is why he sometimes has a problem with television shows that emphasise competition and trendy dance instead of making an attempt to improve the dancing, or the dancers. “Dancing is for expression, not just for television. It is for people to express ideas. I’ve been a big critic of shows like that because it is a competition, and competition puts people in a box. They all want to be better than everyone else.

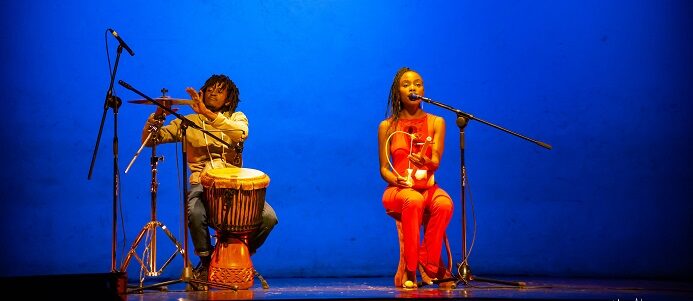

Labdi | Music interlude during 2021's Dance Life Festival ©Ray Ndikwe

Dance Life Festival is more about whether you have a story that you want to tell. A story or an expression is not in competition with other stories or expressions.” Adam, of course, is a dancer himself, and so intimately understands the implications of what is out there in terms of what is offered to people who simply want to dance. “I have been dancing, really, since childhood. I grew up in a house where expression was encouraged.” At school, over holidays, he would dance—the ‘old school’ genre of breakdancing had just taken hold—but he never considered himself a professional dancer. “You know our system. I grew up and stopped thinking of being a dancer. But then I realised that I like this thing—and I have always been the person to do what I like, what I enjoy. It is second nature to me. I didn’t go to dance school, but going to workshops, residencies, and things like that, built my dance vocabulary. I met other dancers, other choreographers.” Other people with ideas like him, in an environment that made sense. He adds that the festival also gives people an environment to learn how to present their work, and find an audience even among dancers themselves. “At the festival, established artists see who is upcoming, and vice versa. Contemporary dancers learn from, say, hip hop dancers. It’s an exchange.”

Labdi | Music interlude during 2021's Dance Life Festival ©Ray Ndikwe

Dance Life Festival is more about whether you have a story that you want to tell. A story or an expression is not in competition with other stories or expressions.” Adam, of course, is a dancer himself, and so intimately understands the implications of what is out there in terms of what is offered to people who simply want to dance. “I have been dancing, really, since childhood. I grew up in a house where expression was encouraged.” At school, over holidays, he would dance—the ‘old school’ genre of breakdancing had just taken hold—but he never considered himself a professional dancer. “You know our system. I grew up and stopped thinking of being a dancer. But then I realised that I like this thing—and I have always been the person to do what I like, what I enjoy. It is second nature to me. I didn’t go to dance school, but going to workshops, residencies, and things like that, built my dance vocabulary. I met other dancers, other choreographers.” Other people with ideas like him, in an environment that made sense. He adds that the festival also gives people an environment to learn how to present their work, and find an audience even among dancers themselves. “At the festival, established artists see who is upcoming, and vice versa. Contemporary dancers learn from, say, hip hop dancers. It’s an exchange.”

The thing with the dancing business, also, is if there is not a structured event like the Dance Life Festival, it is hard to have something that resembles a regular gig. Even the festival only happens once a year. “Goethe-Institut provides a space for people to do what they do best. I am facilitating that space. We are making it possible for them to reach their full potential, to make things, to experience things, to connect, to see what people are doing now, to see that this is what is happening.”

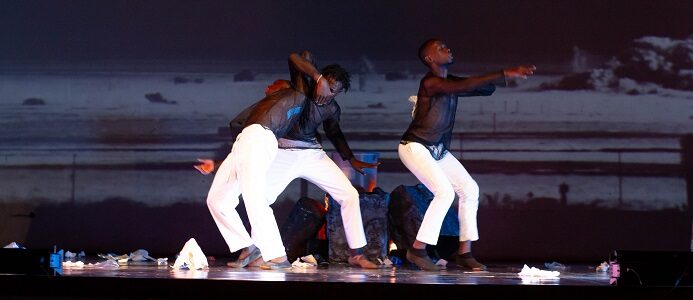

Roy Wanda & Friends | Dance | Ash and Dust © Ray Ndikwe

The reminder is important for dance to be seen in a different light, and start the revolution that Adam is a part of. “People are starting to see that in the evoking of emotions and thoughts and ideas, you can also have a message. People come to reflect, not just to cheer.”

Roy Wanda & Friends | Dance | Ash and Dust © Ray Ndikwe

The reminder is important for dance to be seen in a different light, and start the revolution that Adam is a part of. “People are starting to see that in the evoking of emotions and thoughts and ideas, you can also have a message. People come to reflect, not just to cheer.”

He mentions the role the festival has in building these audiences. “It’s the way Kenyans don’t relate to contemporary dance, specifically. I remember when I started doing contemporary dance, our only audiences were expatriates. Before that, when I was dancing African cabaret at Safari Park, it was the same.” He describes how robust and technical the Safari Cats, as they were known, were with their choreography. It was one of the only professional dance companies around at the time. “But I was bored. I was falling off my chair with boredom and I wanted something more.”

Though he can’t speak for the Kenyan dance industry as a whole, he says that what we’re struggling with is a cultural attitude towards dancing, and an attitude towards dancers. “If you put dancers and actors and singers together, or with any other artists, dancers are always thought of as the lowest in the cast. We’re here to decorate the musician, or the set; act as accessories for the ‘real art’ going on. But then you meet a dancer like me, whose whole career has been nothing else but dancing for the art of dancing. Those attitudes need to change, so that people can start developing a culture of engaging with dance in a way that is not new, but in a way that we are not used to as people in Kenya.” He means, clearly, in terms of treating dance as a valid, professional art. “All over the world, people treat dance like something to go to theatre for. Here, we’re just entertainers who don’t speak. Before the pandemic, there was a feeling of a surge of dance, but it was more like a surge that is influenced by social media and YouTube—popular dance, like TikTok. It had to be cool or interesting or trendy. For me, I am more interested in the dance that gets people off their phones—gets them to turn their damn phones off!—and give the dancer their full attention, and receive something from the performer. Moving people from the fast-food version (easy, trendy, quick, doesn’t last, has no nutrition) of dance.”

Bomas of Kenya | Dance | Janyadhii © Ray Ndikwe

Though the festival was virtual in 2020 because of the pandemic, in 2021 the festival was back to being offline. “Visibility is little. The industry needs more festivals, more dance events—even more competitive television shows!—it gets people talking about dance and having conversations around dance, which, for me, helps my selfish interests with my career and my vision!”

Bomas of Kenya | Dance | Janyadhii © Ray Ndikwe

Though the festival was virtual in 2020 because of the pandemic, in 2021 the festival was back to being offline. “Visibility is little. The industry needs more festivals, more dance events—even more competitive television shows!—it gets people talking about dance and having conversations around dance, which, for me, helps my selfish interests with my career and my vision!”

Adam has great hopes for what dance is in Kenya, and how the Dance Life Festival can help grow this. “I like more experimental collaborative art where I can connect; like an installation artist who I can meet and we come up with an idea and do something together. Interdisciplinary work is something that I like to do, so that art is not just existing as dance but also creating with other art forms, a new piece of art.” And this is how he tends to pick who is performing at the festival as well: experimental, creative, out of the box collaborations where people can all learn from each other, because everyone is doing a fascinating and different thing. “Performing in the festival means having a concept to communicate. It isn’t about having people apply to perform. When someone wants to be at the festival, I want to go to their studio, see how they work, understand their form, and think, oh, this will add to an evening of performance, and this person will lead to the audience experiencing varied ideas. It isn’t tied to having jazz ballet, or urban dance. We have those too! And we have traditional—we partnered with Bomas of Kenya. We have technical. We have conceptual. We try to avoid redundancy.” And, as you can imagine, the result is an evening, and a festival, of the dreams of dance; what dance is in Kenya today, and a hope of what dance will become in Kenya in festivals to come.

Dance Centre Kenya | Dance | I Am Because You Are © Ray Ndikwe

Dance Centre Kenya | Dance | I Am Because You Are © Ray Ndikwe