Early Music 2017

A Year in the Life of (Early) Music ...

The two major anniversaries of Luther and Telemann dominated the year 2017. Anton Steck, Professor of Baroque Violin, looks back over the year in the field of Early Music and examines current issues concerning historical performance practice.

In the realm of so-called “Early Music”, in particular, a jubilee year is often used to take a closer and more intense look at a composer or an event. In the past this has led to many composers being rediscovered or to them suddenly moving into the listeners’ focus. This was the case in 1988, when the 200th anniversary of Bach's son, Carl Philipp Emanuel, was celebrated and modern-day audiences suddenly started to appreciate his grandiose works, resulting in them being performed ever since in concert halls everywhere.

This orientation towards anniversaries, however, can also be somewhat one-sided and does not necessarily lead to a composer or an event becoming a hit. Not so in 2017 - there were actually two heavyweights to be celebrated and both had had a significant influence on music and on Europe in different epochs: Martin Luther and Georg Philipp Telemann. First of all, Luther of course stands for the word, for the German language. Without him, the development would have been much slower - the printing press did the rest, enabling the new German language to spread very quickly throughout the country. Numerous sayings and many words still in use today in German (such as Morgenland/the Orient or Herzenslust/heart’s desire) sprang from his pen and academia agrees that there would have been no Bach without Luther. The most famous example that proves this is the cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress is our God) - number 80 in the Bach Works Catalogue. That was just the first of the 13 Luther-inspired cantatas Bach composed almost 200 years after the Reformation. These 13 works known as the Luther Cantatas were recorded for the Deutsche Harmonia Mundi label by the Cologne-based, early music specialist, Christoph Spering, with his ensemble Das Neue Orchester, for which they were awarded the 2017 Echo for Classical Music - a German award for outstanding achievement in the music industry.

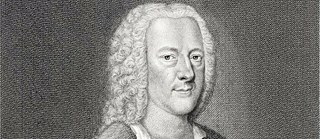

If you were to type “Luther 2017” into a search engine, you would see just how diverse, and even opulent, the commemorative events throughout Germany were. Interesting connections were also set up with the art scene, for example, with Lucas Cranach the Elder, who was a friend of Luther, painted his portrait several times and developed into the painter per se of the German Reformation. This shows just how important the links between art, music and language are. Georg Philipp Telemann was also quite taken with Luther's writings and his command of language. 2017 marked the 250th anniversary of his death. Both of them were considered Europeans, because both of them were famous beyond their national borders. One triggered a Europe-wide dispute with his declarations and criticism of the way religious worship was practised, the other launched a successful attempt to unite the musically hardened fronts between the Italian and French musical approaches. With “les goûts réunis” Telemann created a new, international musical language, the “reunited tastes” prevailed in Europe for more than three decades until the Enlightenment brought the next change in musical taste.

In order to commemorate this musical grandmaster, ten of the places Telemann lived and worked in, both in Germany and abroad, decided to work together. The cities of Magdeburg, Claustahl-Zellerfeld, Hildesheim, Leipzig, Zary (formerly Sorau) and Pszczyna (formerly Pless) in Poland, Eisenach, Frankfurt on Main and Hamburg, as well as Paris, teamed up to form a Telemann network to coordinate their main events and, in a joint publicity presentation, to post the events on the Internet in the form of a program book. Each of these cities organised festivals, some big, some small, and that is why it was possible for people in Hildesheim, for example, to see and hear Telemann's version of Orpheus. The staging was historical, lit only by candlelight, an approach that has become the trademark of the Belgian director, Sigrid T'Hooft. T'Hooft also encouraged the singers to use gestures that emphasise the words of the arias and recitatives. The local orchestra was equipped with Baroque bows and enhanced by Baroque specialists. With this work, too, at its premiere in Hamburg in 1726, Telemann proved to be a true European: the typical Italian bravura arias were sung in Italian, the arias composed in the French style in French and the action generally in German.

2017 and young, newcomer talent

There were also interesting developments in this area. Germany is one of the few countries where Early Music is one of the basic subjects at most music colleges and can be studied in all its different facets - be it “only” as a minor subject, as a second major subject or as the main focus of a Bachelor’s and/or Master’s degree program.Young, newcomer talent, however, does not just come to light when up-and-coming musicians start a course of study in music, and that is why the music schools are now extending their range of training. That is why it is also not so surprising that, at its competition in Leipzig in March, the Deutsche Musikrat (the German Music Council) approved the recorder as a music discipline. The harpsichord was introduced as a discipline just a few years before and, as a result, 2017 saw ensembles performing in a variety of formations playing historical instruments. This development is due to the fact that the younger generation is showing a great interest in Early Music. This has meanwhile led to the formation of several Baroque youth orchestras - here are two examples: Since its founding in 2012, the Jugendbarockorchester Rheinland (Rheinland Baroque Youth Orchestra) (based in Bonn / under the direction of Sylvie Kraus) not only performs concert programs, but also entire operas (such as Purcell's Dido & Aeneas) that are staged in collaboration with the Bonn Opera House.

The Landesjugendbarockorchester Baden-Württemberg (the Baroque Youth Orchestra of the State of Baden-Württemberg) (based in Freiburg / under the direction of Gerd-Uwe Klein, patron is the Freiburger Barockorchester /Freiburg Baroque Orchestra), however, is mainly focused on instrumental and choral music and, since its inception in 2015, has seven major projects under its belt, each with a final concert. Both ensembles are often supported by professionals such as musicians from Concerto Köln (for Bonn) or lecturers from the Musikhochschule Trossingen or members of the Freiburger Barockorchester (for Freiburg). This gives the very young musicians the chance to gain insights into professional orchestral work and to be part of a performance before they start their studies.