Map of Dreams

“We Are All Part of the Fabric”

The Argentinian photographer Martín Weber asked Latin Americans about their dreams. From that emerged a moving photography project and a documentary about the desires, fears, and struggles that define life in Latin America.

By María Alejandra Pautassi

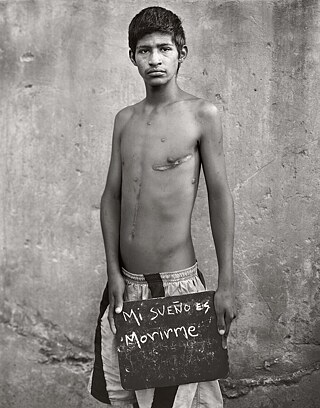

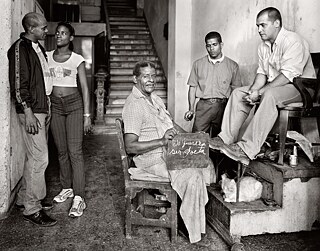

What is Latin America and what does it mean to be Latin American? These are the fundamental questions among those raised by the project Map of Latin American Dreams by Argentinian photographer Martín Weber. Between 1992 and 2013, Weber traveled through more than 50 cities and ten countries on the continent, asking residents to write down their dreams on a handheld chalkboard and be photographed. His objective was to retrieve direct testimonies about some of the major events in recent Latin American history. The result of Weber’s trek was, first, a photo book published in 2015 with 110 photographs and chronicles, and later, an impactful documentary film released in 2020 at the prestigious festival Cinelatino — Rencontres de Toulouse in France.

Martín Weber’s photographs reveal a contradiction between individual desires and structural inequalities, but they also show a glimpse of resilience and hope. Today, 30 years after his initial work on the subject, Weber tells us about us about the concerns, journeys, and encounters that gave rise to his Map of Latin American Dreams.

The Beginning of the Journey

I kept a list, taking into account gender, age, social status, ethnicity ... I was interested in creating a record of inclusion. The objective was always to preserve the dignity of the people, tell their stories, and show that they are all connected, that we are all part of the same fabric.

Being LATIN AMERICAN: An IDENTIty lOCATED IN THE FUTURE?

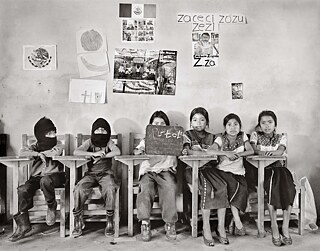

That was exactly one of the questions that I had in the 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s, when I began the project. Back then, Latin American movements were very strong. But I believe the project transcends categories; the aim was for us to find our humanity in ourselves, in something that we all share. The project is more an accumulation of questions than of answers. It leads us to ask: What do we share? What makes us different?Regarding Latin American people, I think that it has to do with proximity and distance. All the stories that I gathered allow us to think about a dynamic between the individual and the collective, between the personal and the absence of government. In the project, singular and illuminating stories stand out like the one about a 60-year-old mother in Guatemala who carries an axe, working for the dreams of others. Regarding the collective, there are, for example, the stories of the Mexican Zapatista movement that chose to take a different path saying, “they believe an army is wrong in choosing peace.” These are stories about the choice between life and death, and they chose life. This is extremely illuminating and particularly characteristic of Latin American expressions of resilience.

SHARED LATIN AMERICAN DREAMS

In general, it’s not about me arriving at conclusions. The project aimed to elicit questions in all of us because each of us can arrive at different but equally valid answers. The project mobilized a series of questions that, as Latin Americans, we needed to ask. Questions like: Where are we and where do we want to go? In my case, as I say in the photo book, it took me 40 years to understand why I was born in Chile: to understand that I had been born in exile. The project is about something very strong that must be seen through family ties and through migration, which has left its mark on us. It is also about the context of the native populations and the convergence of two cultures that have intertwined us, a process in which we are still involved: we still need to acknowledge the place we occupy on one side or the other. I believe that we need to achieve the balance of agreeing to disagree. That is our great challenge. To ask ourselves: What conditions are we replicating that are making it impossible to realize those dreams? Or: What conditions do we need to incorporate so that those dreams can materialize?

LESSONS LEARNED

This project was based on trust. It surprised me to see that 99.9% of the people agreed [to be part of the project]. But how often does someone go up to you and ask you what it is that you want? And how often are you really willing to listen? That creates a very strong bond. Political ads and campaigns — propaganda in every sense — recycle our dreams. That has left us quite alienated. But when the question about dreams comes up so spontaneously — so honestly, so clearly — it brings people together. It creates an encounter and that is something that the project aimed to capture: the moment when two people meet and share a space and a moment. My greatest lesson was discovering that we are all connected. I laugh because lately I have been using the word “weaving” a lot, and my last name, Weber, speaks exactly to that: it means weaver. I learned that we are connected and that the only way to improve our position is to do it together, respecting our differences and identifying areas of common ground.

LATIN AMeRICA: bETWEEN DREAM AND NIGHTMARE

There is something in every story. What became clear and what I have been asked, is why the photo “Mi sueño es morirme” (“My Dream Is to Die”) is on the cover of the book. The answer is perhaps too simple: it is the dream that you never wanted to find. Six months after I finished the book, I was told that Cristián, the boy in the photograph, accomplished his dream.