From literature to media and culture, the Arab diaspora has shaped a hybrid imaginary, where Brazilians have become “Arabized” and Arabs have become “Brazilianized”. From the journalistic production of children of immigrants to the incorporation of references to the national literary narrative, the Arab legacy is an essential part of the Brazilian cultural universe.

“Coming from different regions were backlanders, Sergipeans, Jews, Turks — they were called Turks, those Arabs, Syrians and Lebanese — all of them Brazilians,” says the narrator in the Discovery of America by the Turks, by Jorge Amado (1912-2001). The book tells the story of Raduan Murad and Jamil Bichara, immigrants who landed on the coast of Bahia in 1903, in search of the bonanza that was promised by cacao exploitation.Amado wrote the text in 1991, at the invitation of an Italian agency commemorating the fifth centenary of the “discovery” of America. In a jocular tone, the title plays on the notion of discovery, attributing the gesture to the “Turks” — not to the Italians or Portuguese. In Brazil, the use of “Turks” to designate “Arabs” is an ethnic mix up dating back to the beginning of immigration. Because they were under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, emigrants entered the country with Turkish passports and were mistakenly called this.

The Arabic accent appears extensively in Amado’s work. Nearly all his novels feature characters of Arab origin, such as Fadul Abdala in Show Down and Nacib in Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon. In addition to Amado, other artists portrayed a new cultural melting pot resulting from immigration: the poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902-1987) wrote Os turcos (The Turks), a poem about recently arrived immigrants in the state of Minas Gerais; in Grande Sertão: Veredas (Bedeviled in the Badlands), João Guimarães Rosa (1908-1967) features the character Assis Wababa, a Turkish merchant in the semiarid interior of the country.

Even before the diaspora, Arab imagery was present in the references of national authors such as Machado de Assis (1839-1908) and Gonçalves Dias (1823-1864). Even Dom Pedro II (1825-1891), the last emperor of Brazil, nurtured affection for the theme, in the Orientalist fashion of the period. A polyglot, he had some knowledge of Arabic and attempted to translate some texts into Portuguese. His notebooks include a translation of the classic One Thousand and One Nights, covering 84 nights (between the 36th and the 120th). The monarch was the first person to translate the text directly into Portuguese; the manuscripts are housed at the Imperial Museum of Petropolis in Rio de Janeiro.

A Diverse Community

In the context of immigration to Brazil, “Arab” designates a specific segment of a diverse community, whose current makeup encompasses 22 countries across North Africa and the Middle East. Immigrants were mostly Christians from Lebanon and Syria. The numbers vary, but it is estimated that the peak of migratory flow occurred between 1880 and the mid-20th century. By 1920, 58 thousand Syrian and Lebanese had officially entered the country, according to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics.Certain peculiarities marked the integration of Arabs into Brazil. Unlike European immigrants, some emigrants rejected rural settlement and wage labor, preferring self-employment and urban centers. Many worked as peddlers and freelance professionals, creating a business class. The retail tradition is still visible today in popular shopping malls like Rua 25 de Março in São Paulo, and at Saara in downtown Rio de Janeiro, both historically associated with Arab presence.

In addition to workers, an intellectual elite was forced to migrate. “People arrived in precarious conditions, but there was also immigration of intellectuals, people who worked as journalists and editors in the region of the former Greater Syria,” explains Christina Queiroz, PhD in Arab Studies at the University of São Paulo (USP) and one of the directors of the Institute of Arab Culture. “They were also heavily involved in book publishing in Brazil, but it was the press that was actually more recorded and researched,” she adds.

Hundreds of Periodicals

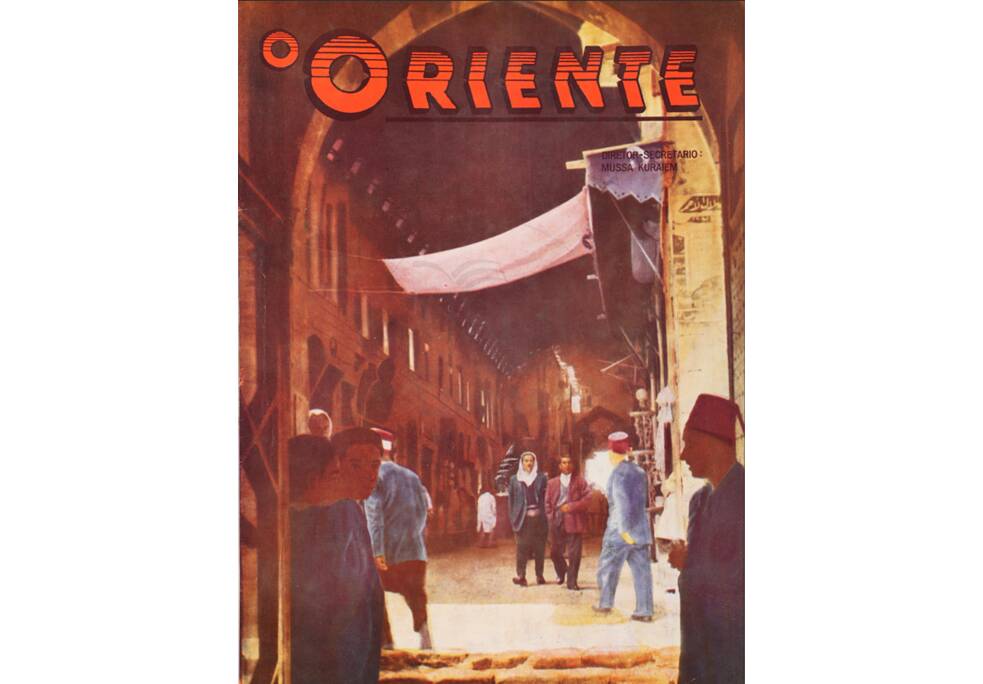

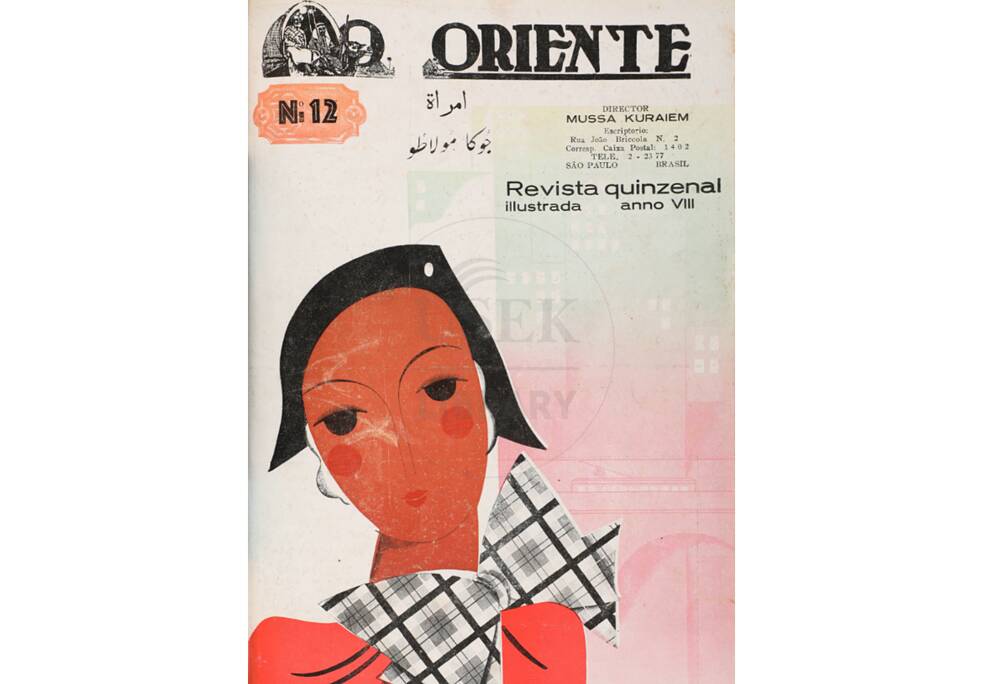

If its presence in commerce and cities gave the community visibility, it was through the press that it gained a voice of its own. Starting out as an alliance between the economic and intellectual elite, an Arab press circuit flourished in Brazil. One of the longest-running publications of that circuit, the magazine O Oriente (The East), was published between 1927 and 1974 by journalist Mussa Kuraiem (1894-1974), the son of Lebanese immigrants, who was born in São Paulo.

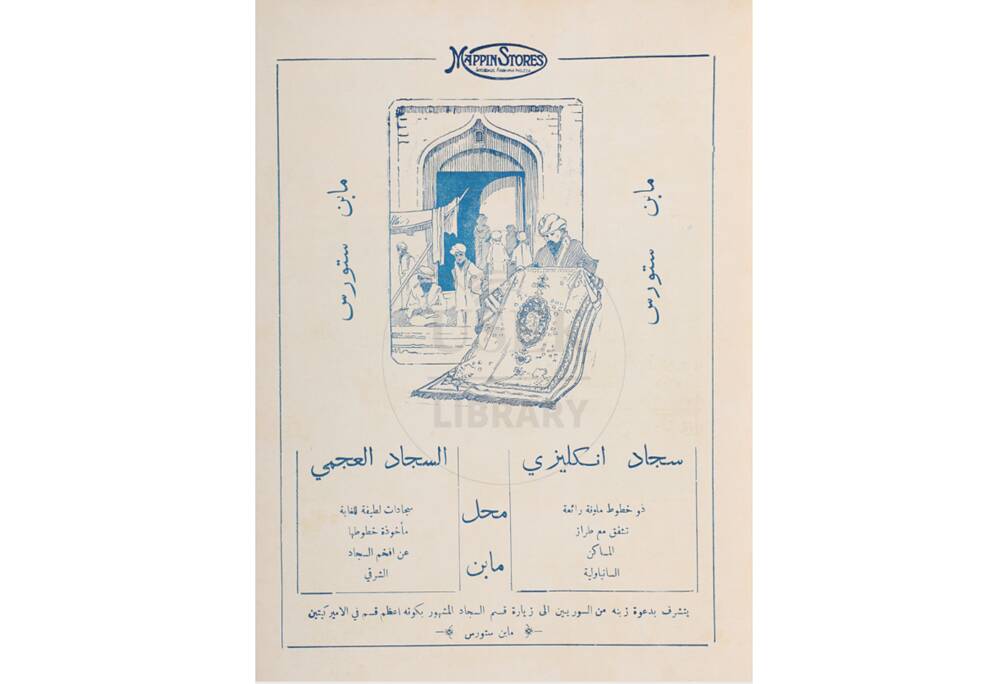

“There are countless advertisements for the textile industry in O Oriente magazine, supported by businesses among other things. There are mentions in the articles themselves, in the editorials, thanking the magazine for its support,” Queiroz explains. Between 1890 and 1940, about 400 periodicals were published in states such as Amazonas, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Many of them were written entirely in Arabic, but there were Portuguese and bilingual editions as well.

Literary Writing

The effervescent press of the time was the scene of a new development. “The diaspora to America was marked by the phenomenon of Mahjar, a movement of literary writing and intellectual production outside the Arab world, but written in Arabic,” says Matheus Menezes, a doctoral candidate at USP whose research focuses on the journal of the Andalusian League of Arab Writers. The League is one of the main literary groups of the Arab community in Brazil, and it published its magazine between 1935 and 1953. “The Mahjar [literally, “place of immigration”] is an extension in the Americas of Nahda, an Arab “renaissance” movement that grew out of contact between indigenous Arab and European thought,” he explains.The Mahjar in Brazil featured prominent figures of Arabic poetry, such Chafic Maluf (1905-1976), the author of books such as Abqar (1936). The League’s magazine also published women authors, such as Lebanese Salma Sayegh (1889-1953), who dedicated a text to women in Brazilian literature, focusing on the journalist and writer Helena Silveira (1911-1984). Silveira, in turn, was married to another prominent intellectual in the community, Jamil Almansur Haddad (1914-1988), a translator, critic and doctor. Haddad was the first to translate the French poet Charles Baudelaire’s (1821-1867) The Flowers of Evil in its entirety into Portuguese.

The National Narrative

Acculturation to the Portuguese-speaking world intensified starting in 1938, during the Getúlio Vargas government, which forbade publications in foreign languages. In the second half of the 20th century, the Arab presence took on new dimensions through authors who were descendants of emigrants, most renown being Milton Hatoum and Raduan Nassar, who established a new step in the process: the incorporation of a certain Arab experience into the national literary narrative itself.In his two first novels, Relato de um certo oriente (Tale of a Certain Orient) and Dois irmãos (Two Brothers), Hatoum places characters of Lebanese origin in the heart of the Amazon, alluding to the community that emigrated to northern Brazil, addressing themes such as memory, family and identity. The two works were adapted for film.

In Lavoura Arcaica (Ancient Tillage), Raduan Nassar evokes Arab heritage more opaquely. In retelling the parable of the prodigal son, his poetic prose suggests this legacy discreetly: through allusions to the dabke, a Lebanese folk dance, to the proverbial “Maktub” uttered by the grandfather character, and to the patriarch’s sermons. Like Hatoum, Nassar approaches the world of Lebanese families in Brazil from an internal perspective, with a myriad of Biblical and cultural references from the Semitic Mediterranean. Different from Amado and Drummond whose “Turks” are foreigners in a strange land, Nassar’s and Hatoum’s Arabs are already Brazilian — in their own way.

This article was produced in collaboration with Humboldt, the regional magazine of the Goethe-Institut in South America.

October 2025