KinoKonzert 2019

The Golem: How He Came Into the World

To peer at an expressionist work is to bathe in emotion. In its visual forms, the artistic movement splashes mood and feeling across its chosen media, whether in the brush strokes and colour selections that dance across a canvas, or in the lighting and camera placement that defines filmic images. The style of an expressionist piece is immediately apparent, and so is the act of conveying complex sensations and sentiments through symbolism. Looming shadows and lurid hues will do that. So will the art of framing an agape face so that it instantly reveals all of its secrets.

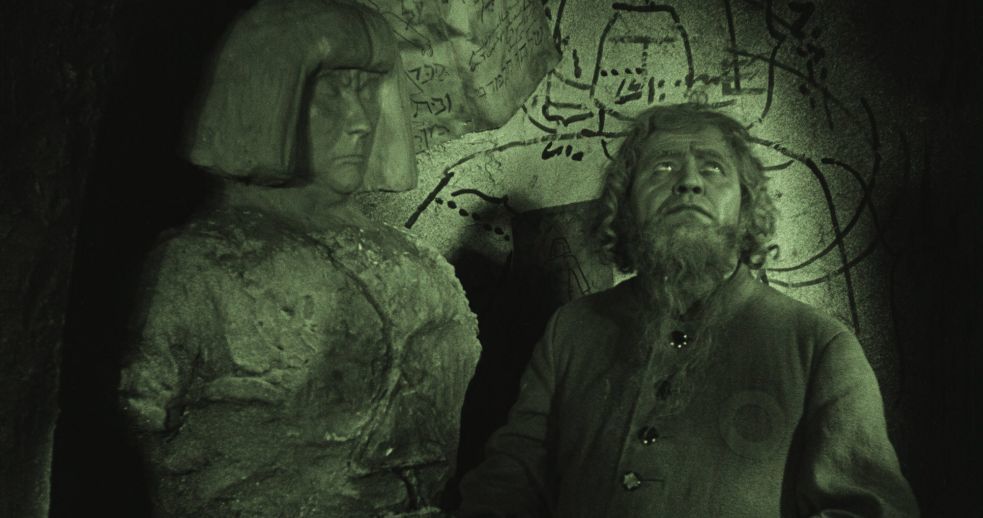

Any sequence from 1920’s The Golem: How He Came Into the World makes the case for expressionism as an evocative cinematic outlet; indeed, when the movement came to the movies more than a century ago, the marriage immediately proved a happy one. On a big screen, writ large and flickering with a projector’s whirl, every vivid, precisely composed, emotionally laden image both sings and screams. And while it wasn’t German expressionism’s first film, or its first feature-length release, or even the first moving picture to adapt this specific piece of ancient Jewish mythology, The Golem couldn’t have had a bigger impact.

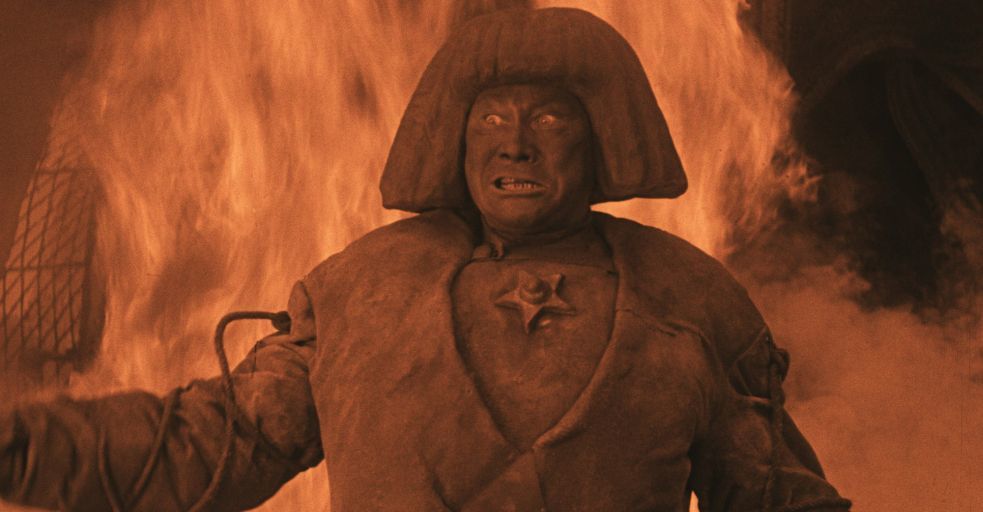

Recently touring the country as part of the Goethe-Institut’s KinoKonzert series, The Golem makes its mastery known in every frame. It’s a feat of visual splendour — of finding an exacting image for every feeling and moment, and of steeping viewers in a particular emotional and contemplative headspace in the process. Its early moments brood. Latter sequences burst with brightness and hope. When calamity strikes, the film makes every jagged, angular line of its monochrome tableaus jut and pierce.

Unleashed Desire and Potential Damnation

Both co-directed by and starring Paul Wegener, the 76-minute movie unfurls one of the oldest stories there is: of unleashed desire and potential damnation. In medieval Prague’s Jewish neighbourhood, Rabbi Loew (Albert Steinrück) foresees dark times ahead, a prediction that seems accurate when a knight, Florian (Lothar Müthel), is sent by the Holy Roman Emperor to deliver news of the community’s forced removal. In response, the Rabbi brings his secret creation, the golem, to life. Sorcery, including summoning the spirit Astaroth, is called for to achieve the task. This magical deed is meant to save the Jewish people; however messing with otherworldly forces is rarely so simple, especially when combined with humanity’s fickle impulses.With its towering frame and helmet-like hair, the golem (Wegener) proves both an imposing and impressive figure. The Emperor is suitably wowed, and the Rabbi understandably relieved. Alas, in the interim, Florian has fallen for Loew’s daughter Miriam (Lyda Salmonova), which his assistant (Ernst Deutsch) — who also harbours his own affections — discovers. Accordingly, what begins as a story of mystical creation out of a desire to do good becomes one of disastrous supernatural chaos undone by libidinous desires. The golem came into this world as an agent of change, but rampages through it as a warning as much as a saviour.

Co-helming with Carl Boese (Nocturne of Love), co-writing with Henrik Galeen (who would also pen Nosteratu, as adapted from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, two years later), and working from Gustav Meyrink’s novel, Wegener taps into themes as resonant and timeless then as they always had been in Jewish lore — and, as they still are today. How one endeavours to shape the world with their will, attempts to act on their needs and yearnings, reconciles the terrifying true nature of life and death, and realises that even their most noble intentions can go astray are all notions that have not, and will never, become obsolete. Nor, at their darkest points, will they ever stop inciting horror of both the physical and existential kind. To face the fact that we’re nothing more than flesh and impulses, and that both can be corrupted, is chilling to the bone.

A Transformative Influence

These ideas recur among The Golem’s expressionist brethren, in different variations. To name just a few, they’re evident in Robert Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which preceded The Golem’s release by mere months; in Nosferatu, blatantly; and in F.W. Murnau’s Phantom, even with its romantic fantasy. The path from German expressionism to 1920s and 1930s Hollywood horror, including The Phantom of the Opera, Dracula and Frankenstein, is well-documented; however it’s a pivotal, transformative connection.In movies such as The Golem — Wegener’s third take on the tale, after the now-lost 1915 film entitled The Golem (without a subtitle) and 1917’s similarly unavailable comedy The Golem and the Dancing Girl — humanity’s base instincts and deepest fears glimmer and flutter. That’s what horror is all about, and the through-line from myth to gothic literature to expressionist cinema to unsettling movies as we now know them is easy to discern. Features such as The Golem give our frights and woes not only flickering visual form, but expressive emotions that needle their way into our brains after a mere split-second. They’re a projection and a mirror, all at once.

With this in mind, it’s hardly surprising that Roger Ebert has argued that The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is the first true horror film. Lesser known, outside of cinephilia, The Golem: How He Came Into the World belongs in such company.

The bonus, for KinoKonzert’s screenings of The Golem, came not only from a gloriously and carefully restored version of the movie, but from Lucrecia Dalt’s live score — which, with its wide-ranging sonic sources, and eerie, industrial feel, give the German expressionism great a pitch-perfect soundtrack.