Jaana Pesonen

Describing diversity in 21st-century Finnish children’s books

I bite my lip. I clutch my phone.

“Silence is sometimes as loud as a roar,” my father says, “so far is just like being close. And even if you’re away, it’s just like being together.”

I know that silence is sometimes a roar.

But I don’t know how

far is close and away is together.

By Jaana Pesonen

The girl Sama in the picture book Siinä sinä olet (Tapola & Durubi 2020; There You Are) misses her father immensely. She packs her bags and gets ready to go to her father. But her father is far away, in another country. Missing him is not made any easier by the fact that Sama’s little brother gets to talk to their father on the phone for longer. The call is disconnected before Sama gets her turn. Siinä sinä olet is a beautiful and wistful story of longing. Sama’s story can be read as narrative of families in which one parent has to move to another country for work. The story could also be about being a refugee, because in the world today, more people than ever are forced to leave their homes because of war, violence, or persecution. Regardless of nationality or geographical location, the focus is on longing for and missing your loved ones. The book does not describe difference as elsewhere, far away from us. Siinä sinä olet is a good example of Finnish children’s books today, in which national, ethnic, or religious diversity is natural for the characters.

Diversity is defined here as dynamic and changing distinguishing factors, including ethnicity, socio-economic background, religion/no religion, gender, ability, and sexual orientation. These factors affect belonging and inclusion for individuals and groups of people, especially minorities, because we use these distinctions to give meaning to the difference between “us and others.” As in previous studies of children’s literature (e.g. Botelho & Kabakow Rudman, 2009; Bradford 2007) have shown, describing multiculturalism is often associated with presenting other cultures as distant, exotic, and mystical. These representations have confirmed the contrast between “us” and “the others,” or civilized and uncivilized people. Australian children’s literature scholars Debra Dudek (2011) and John Stephens (2011) have both written about the challenges of describing multiculturalism. According to Dudek, it is impossible to avoid tensions when discussing multiculturalism. Stephens sees superficial presentation of multiculturalism as a particular problem; he ascribes this to the focus on difference. Since in the vast majority of stories, people belonging to the majority culture are in key roles, meanings are constantly constructed from the perspective of the dominant culture. (Stephens 2011, 18–19.)

Multiculturalism described in Finnish children’s books has been studied to some extent (see e.g. Heikkilä-Halttunen 2013; Pesonen, 2015; Rastas 2013). Learning related to books addressing multiculturalism is beginning to be researched more (see e.g. Aerila 2010; Pesonen 2019). However, the terminology, such as multicultural children’s literature, has not been subject to the same kind of academic and public debate as, for example, in the United States. For Anna Rastas (2013, 13), the concept of multicultural literature provides tools for analysing literature published in Finland. However, she stresses that the concept is not unproblematic, because it usually refers only to racialized social relations, and not, for example, to different languages or religions. Researchers have also shown that the way Finland and Finnishness is described in children’s books sometimes strengthens the division between “us Finns and those foreigners” (e.g. Heikkilä-Halttunen 2013;. Pesonen, 2015).

In this article, I base my approach on intersectionality theory. This enables and encourages us to critically evaluate our understanding of diversity and social categories as distinguishing factors. Intersectionality is a suitable tool for analysing various social categories (such as ethnicity, nationality, gender, language, ability, and age), for making them visible and deconstructing them (Pesonen 2015). Intersectional analysis requires awareness of complex power relations and understanding of the fact that individuals – including minorities within minorities – belong in multiple ways and should not be grouped as belonging to specific and narrow categories (Crenshaw 1991; Yuval-Davis 2009). Awareness of the balance of power and attempts to break it down in the study of children’s literature have also motivated the Finnish children’s literature scholars Mia Österlund, Maria Lassen-Seger and Mia Franck (2011). In their view, the study of multiculturalism can and should take into account multiple and overlapping ideological and social tendencies, even contradictory discourses.

In this article, I examine descriptions of diversity in 21st-century Finnish children’s books. I ask: How is diversity described in 21st-century Finnish children’s books? I also consider whether representations of diversity have changed, by comparing books published in the 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s. The analysis is inevitably linked to challenges and tensions inherent in the concepts of diversity and multiculturalism that I have already mentioned. I present eight Finnish children’s books here, some of which are picture books, while others are illustrated books. Some of the books are part of a series, in which case I briefly introduce other volumes in the series. This sample is not a comprehensive overview of multiculturalism in 21st-century literature, but I aim to present a wide range of perspectives on the subject.

Diversity in stories about refugees

The history of describing diversity is associated with themes of being an outsider and alienation, but also stereotypical and racist representations. Minorities in particular have generally been portrayed through simplifications related to ethnicity and social class. Tokenistic, that is, superficial and ostensible, representations to make the story appear multicultural have been common. (e.g. Botelho & Kabakow Rudman 2009). In recent years, the number of new children’s books about refugees has risen considerably. Descriptions of war are known to increase the risk of classifying people into “us and others” in children’s books (Meek 2001), so I examine ways of describing refugees particularly from this perspective. In brief, refugee narratives tell stories of people seeking asylum. Children’s literature researchers have considered how refugee stories have been used to increase empathy and understanding. Instead of providing statistics, these literary pedagogical perspectives focus on more personal and more meaningful experiences (Hope 2017), as well as on making the refugee perspective and voice heard (Arizpe 2010; Nel, 2018). In Finland, children’s literature publishers, authors, illustrators, and characters, however, are still largely white Finns (Oikarinen-Jabai 2009; Rastas 2013). Refugee narratives create an opportunity to make the voices of people defined as minorities heard; there is a need to critically examine the power relations in this and reflect on how these stories confirm the distinction between “us” and “others,” or whether they may produce other perspectives on the lives of people who end up as refugees (Pesonen, 2020).In Finland, refugee narratives in children’s literature are still few and far between. The picture book Siinä sinä olet (2020) can be interpreted in part as partly addressing this theme, as the father of the family in the story is already in another country, where the rest of the family hopes to get to. Refugee narratives, however, most often centre on the journey itself: within this, the sea crossing has become almost iconic (Vassiloudi 2019, also Pesonen 2020). Hence Siinä sinä olet is an exception, as it centres on the child missing one of her parents. A significant part of the story is about feeling bad and frustration, which the protagonist, Sama, also takes out on her mother. The fact that Sama’s father is elsewhere could be interpreted as due to labour migration. The author Katri Tapola, however, said that the book is about being a refugee, and the impact of this on people’s lives. The story does not provide clear answers, and it does not tell readers whether Sama, her little brother Nagim, and her mother will be reunited with her father. This is lack of clarity is one of the strengths of the story in Siinä sinä olet. Ultimately, the key thing is that it is possible to live with longing for and missing someone. Calls with the father are difficult, as Sama does not know how to tell him that she misses him and feels bad. Nevertheless, the father senses Sama’s feelings, and knows how to comfort her. Sama and her father talk about dreams and the future, and Sama feels as though her father were close again. She feels better, and joy returns to her life. At the end of the story Sama is playing with her little brother that they are travelling to see their father.

Siinä sinä olet is a bilingual picture book, with the Finnish text and Arabic translation side by side on each double-page spread. Making the picture book bilingual is timely in a modern-day multilingual society, but also necessary. Finnish early childhood education and primary school teachers require language expertise, and need to create a language-conscious learning environment for all children in education and care. For this reason, books in which bilingualism and multilingualism is a natural part of the story are in demand. A different linguistic perspective on a refugee narrative is given in the Finnish publication entitled Meidän piti lähteä (Pelliccioni, 2018; We Had to Leave). Meidän piti lähteä is a wordless picture book, which tells the story of one family escaping a war zone. The wordlessness of the book enables readers of different ages to interpret the images according to their own understanding, and verbalize the story in their own language. Without words, it is possible to make the story and characters more diverse, for instance in terms of nationality, ethnicity, or religion. On the one hand, readers have to do more work to interpret the images than simply reading the text. On the other, the images allow the story to be interpreted in different ways.

As in Siinä sinä olet, the protagonist of Meidän piti lähteä is a little girl. At the beginning of the story, the family enjoys a peaceful life in their own home. Immediately, war breaks out; on a black double-page spread, planes drop bombs exploding on a city at night. The war begins very suddenly, and the story tells us nothing about the background or reasons for it. The journey to safety plays a central role and is described in most of the book. The family travel by different means of transport and on foot. They spend the night outside, and finally arrive at the seashore, where they are directed to dinghies. The sea crossing is the heart of the story, and the most threatening part. The sea is portrayed as endless and dark; on it, the small red rubber dinghy almost disappears. Overcrowded dinghies at sea have become one of the most recognizable visual images of our time. In recent years, these images have been in the news and featured in various media so often that they have become an iconic part of stories about refugees. Partly because of this, the narratives do not portray refugees as facing any other dangers or trauma, such as walls and fences, homelessness, abuse, or loss of a family (Vassiloudi 2019, 38). Meidän piti lähteä also portrays the period after the sea crossing in a refugee camp during daylight. In the camp children play together, smiling, and flowers burst into bloom. But when night comes, the tent doorways glow brilliant red in the darkness, as reminders of the horrors of war that people still carry with them.

Siinä sinä olet and Meidän piti lähteä are very different descriptions of refugee situations, but in both books, the protagonist is a little girl, through whom sadness and fear are described. This portrayal of vulnerable minorities, such as refugees, may give an image of the Western world as a benign and offering help, while the Eastern and Southern world are portrayed as weak and in need of help (Vassiloudi 2019, Pesonen, 2020). At the end of the story Meidän piti lähteä shows how the family will arrive by plane on snow-covered ground, where they are given their own home. Settling into their new home country is portrayed by building a snowman with a local child. The wordlessness of the story enables varying interpretations, and on the last page of the book, the author asks the reader to reflect on how the story could continue. Unlike Meidän piti lähteä, Siinä sinä olet does not show the girl protagonist receiving help, nor does it reinforce the configuration of “us” as benefactors giving help to “others” who receive it. Longing and missing someone are central to Sama’s story; the reader may be able to identify with these feelings without any connotation to refugee narratives. Thus, it does not draw such a strong distinction between “us” and “others.”

Difference and ordinariness in challenging norms

Recent Finnish picture books have addressed alienation and difference from a socio-economic perspective. In the picture book Koira nimeltään Kissa (Kontio & Warsta 2015: A Dog called Cat), the main characters are a homeless man and a stray dog. The story is mainly about being an outsider, but also about belonging and friendship, which make it an interesting contribution to the discussion of diversity in 21st-century children’s books. The man in the story who lives on the streets is called Marten, and he meets a stray dog called Cat. Both share the experience of being an outsider, which they did not necessarily choose themselves. When Marten and Cat tell each other about their backgrounds, this is a subtle criticism of people’s narrow understanding of normal and society’s discriminatory structures. The book takes an unusually courageous perspective on otherness and exclusion, because homelessness is not a common theme in Finnish children’s literature. The book received plenty of positive reviews, and was nominated for the 2016 Nordic Council Children’s and Young People’s Literature Prize. The second book in the series, Koira nimeltään Kissa tapaa kissan (Kontio & Warsta 2019; A Dog called Cat meets a Cat) was nominated for the major award, Finlandia Junior. Koira nimeltään Kissa tapaa kissan continues the story of two characters living on the margins of society. The second part tells the story of a real cat joining their company, and telling them about its adventures sailing the seven seas. The first part of the story had already subtly questioned social norms and the desire to live outside them. The cat was given many names on their travels round the world, from Pedro to Lila, and there is no substantial gender confrontation regarding whether they are a “girl” or “boy.” The story also calls into question categories of belonging and exclusion, including gender norms. The cat turns the twosome into a trio; just because they are different, they are not objects of pity. Elina Warsta’s illustrations bring different perspectives, and more content, into both parts of the story. Thus, the books might well be called expanding picture books, because images provide meaning independently of the text.Being an outsider and socio-economic difference are also described in Sorsa Aaltonen ja lentämisen oireet (Salmi & Pikkujämsä 2019; The Duck Who Was Afraid to Fly). Aaltonen the Duck dreams of flying, but is scared of it. The doctor has diagnosed Aaltonen’s fear of flying, and encourages the duck to be brave. The story is about dreams and fears, but also touches lightly on how different individuals have different starts in life. Almost every working day, the duck is queueing for buns outside the food bank with many others who dream about a change in their own lives. The queue reflects the growing inequality in society, and the consequent narrowing of opportunities. From preschoolers to pensioners, people queue to pick up daily food rations: “Someone had got a gig, another had only just got a dummy. But most of all, we talked about one thing: when will we fly south?” Aaltonen is experiencing multiple exclusion: the duck has not been anywhere, cannot fly, is afraid of the doctor, and feels that this means no one can be interested in them. At the end of the story, however, Aaltonen the Duck is encouraged to try and spread their wings. Matti Pikkujämsä has been nominated for the 2020 Nordic Council Children and Young People’s Literature Prize for his colourful acrylic illustrations.

These stories describe outsiders by combining anthropomorphic animal characters with counter-discourses. Counter-discourses, or counter-narratives, can challenge the often-dominant discourses, or narratives of those in power (e.g. Chaudrée and Teale 2013). Both Marten, the homeless man in Koira nimeltään Kissa, and Aaltonen the Duck, who goes to a food bank, are characters that are often portrayed in social debates as in need of help, even failures. Through counter-narratives, however, Marten and Aaltonen the Duck appear as active figures responsible for making decisions about their own lives. Counter-narratives often challenge simplified stereotypes. The key to these counter-narratives is the relationship between image and text, which can tell a story in isolation from each other. In this case, the images expand the narrative of the text. Several of the 21st-century Finnish picture books I present here can be viewed as expanded picture books. Such books are particularly interesting descriptions of diversity, since they enable educational meanings without too much pedagogical emphasis. Like the books about refugees described above, stories about other people living on the margins of society can present diversity of ethnicity, religion, gender, or sexuality as part of today’s society.

Redrawing boundaries between the normal and different

The works I have discussed so far challenge the normative categorization into “different” and “normal.” Challenging the dominant discourses of social and political diversity enables a more diverse understanding of the differentiating factors. In counter-narratives, people and their lives are more diverse; these stories encourage readers to reflect on perceptions and boundaries of the so-called normal (Pesonen 2019). Next, I introduce a few picture books published in the 2010s and consider the meanings and values attached to their representation of diversity. I propose that making diversity an ordinary part of the story and characters shapes our perceptions of difference. For instance, descriptions of minorities do not maintain the exoticizing and patronizing attitude that was widespread in children’s books addressing cultural diversity in previous decades.Tuikun tärkeä tehtävä (Lestelä, 2019; Stella‘s Special Task) is the first book in a series about a preschooler protagonist, Tuikku. The story centres on a quarrel with her good friend, Oiva. The bad words she said weigh on Tuikku so that her stomach hurts. Tuikku’s mother understands the situation, and in the evening they go together to apologize. The story focuses on emotional skills. The quarrel, and feeling bad after it, is a rather ordinary situation for children, which makes it possible for them to put themselves in the other person’s shoes, and invites them to reflect on why apologizing is sometimes hard. This picture book is not about a typical nuclear family, as Tuikku lives alone with her mother in Finland, and her father, who she is close to, lives in Nigeria. The series about Tuikku is a welcome addition to the landscape of Finnish picture books, in which children perceived as coming from ethnic minorities are rarely the main characters.

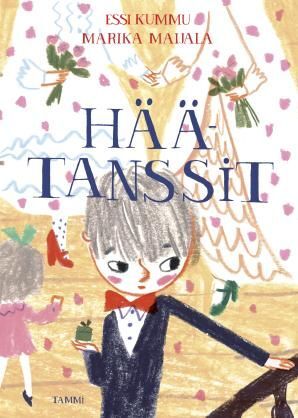

All the books in the Chatty Elias series challenge the assumption of a masculine–feminine binary in many ways. Elias’ father loves baking, but is also said to flex his muscles in front of the mirror. When parents fall in love again with other people, it may even seem frightening to a child, because this violates the safe way things were before. Elias’ mother’s new spouse is a woman, but this issue is not raised specifically at any stage. In terms of hegemonic assumptions in society, the non-heteronormative relationship is not portrayed as any different to the father’s relationship with a woman. Elias’ own masculinity is also described through awakening feelings of sexuality and corporeality; this is done directly, but not didactically. The latest instalment of the series, Häätanssit (2019; Elias and the Wedding Waltz) continues to encourage reflection on growing up, feelings, and interpersonal relationships. Elias’s mother and her partner, Inari, have moved in together, and are going to get married. When Inari moves into Elias’s and his mother’s home she brings her daughter, Helga. For sensitive and emotional Elias, all these changes seem to be too much, and he is moody and cranky throughout the wedding. Elias unburdens himself to his grandfather: Elias lowered his head. It was good, when they’d already split up and me, mum and Inkeri were living on Dandelion Road. Now there are too many people at home and mum is marrying Inari. Granddad had straightened his collar and stretched out the hem of his suit jacket. “Morning,” Granddad said. “I don’t like it at all,” Elias replied. “Why not?” “Because then everything will stay like this!” Elias shouted. “And nothing will ever be the same as before!” (Kummu, 2019, 19). Life in a blended family is sometimes exhausting for adults, too, and one of the strengths of the Chatty Elias series is that it describes both children and adults as having both positive and negative feelings. In terms of diversity, the Elias series, challenges normative assumptions about families, as well as binary conceptions of gender, in an interesting way.

As the books discussed here show, images of family have become more diverse in 21st-century Finnish children’s literature. The first Finnish picture book where the main character’s family had same-sex parents was written by Tittamari Marttinen and illustrated by Aiju Salminen: Ikioma perheeni (2014; My Very Own Family). When it came out, the book shattered a glass ceiling because several characters in the story belonged to sexuality or gender minorities. The main character, Moon, is gender neutral, a more widespread phenomenon in 21st-century Finnish children’s books. Moon’s best friend also has same-sex parents, and Moon’s godparent, Nikki, is undergoing gender reassignment. Ikioma perheeni brought LGBTQ+ families into children’s literature, and received plenty of praise for it. The work was awarded the 2015 Arvid Lydecke Prize. Ikioma perheeni particularly challenged normative conceptions of family. It is much more didactic than the books disused above, and a number of terms – such as “clover family” (apilaperhe, a family with three or more parents from the child’s conception) or the gender reassignment process – are explained to the reader textbook style. This strong didactic grip distinguishes this picture books from others presenting non-normative families which were published later. Yet Ikioma perheeni created a space for stories that face sexuality and gender questions head on.

The last picture book I present here is Muistan sinua rakkaudella (2019, Pelliccioni, Snellman & Szalai; I Remember You with Love). This visually appealing picture book in dark shades is about death, and different ways of grieving. The main character is Alma, whose grandmother has died. Losing her grandmother makes Alma feel sad, but also confused. She wonders why loved ones have to die. Alma tells her friend Diego how she misses her grandmother. Diego says that they remember his dead grandfather or abuelo on the Day of the Dead, which is called Día de los Muertos. Diego gives Alma the idea of assembling various objects that remind her of her grandmother on a table at home, next to her grandmother’s photo. Alma’s mother is moved by the gesture, and the family mourn their loss together. Alma’s parents arrange to meet Diego’s family and spend the Day of the Dead together.

Readers of Muistan sinua rakkaudella encounter different ideas and traditions related to death and remembering the dead. Interestingly in terms of diversity, an unfamiliar custom, the Mexican Day of the Dead, does not appear as exotic or strange. Both the children and the adults in the story are described as approaching different customs and norms with interest and openly. Cultural customs are shown to mix and form new traditions. Thus Muistan sinua rakkaudella does describe cultures, and the norms and customs attached to them, as variable and renewable. This challenges a static and essentialist understanding of “our” and “other” cultures.

Conclusion

In 21st-century Finnish children’s literature, diversity, or categories of similarity and difference, are not as heavily present as in books published in the last millennium. The picture books discussed here feature both children and adults with multiple, changing, but also contradictory identities. Diversity is addressed through themes such as ethnicity, nationality, socio-economic background, gender, sexuality, without highlighting the difference of people defined as belonging to minorities. Diversity has become a natural part of picture books. The boundaries between the usual and unusual are redrawn when diversity is not represented in categories of normal and abnormal. Presenting the ordinary in different ways, therefore, challenges normative conceptions and assumptions about, for example, what a family or a Finn is, as well as the static and essentialist categorization of “our” and “others’” culture(s).Nevertheless, it must be noted that the very postmodern, expanded picture books discussed here do not reflect all children’s literature published in Finland that describes diversity. The diversity described in these books, is a complex, overlapping even contradictory combination of various social categories, such as ethnicity, language, nationality, gender and sexuality, in line with intersectionality theory. The books I examined here can be said to reflect the best descriptions of diversity in that they are complex, even the most complex cases which readers interpret according to their own understanding (Dudek, 2011, 155).

Children’s books in which the distinction between similar and different, us and others, challenges the usual descriptions of diversity, are timely. In Finland, as in many other European societies, neo-Nazi and right-wing extremist attitudes have increased in recent years. The picture books presented here do not declare or demonstrate, but invite readers to look at and reflect on familiar customs, practices, and modes of being that are seen as normal from another, possibly new, perspective. In this way, we can highlight more diverse stories that can broaden our understanding of the ordinary.

References

Aerila, Juli-Anna. (2010) Fiktiivisen kirjallisuuden maailmasta monikulttuuriseen Suomeen: Ennakointikertomus kirjallisuudenopetuksen ja monikulttuurisuuskasvatuksen välineenä. Turun yliopisto.

Arizpe, Evelyn. (2011) “Visual Journeys with Immigrant Readers: Minority voices create words for wordless picturebooks.” Speech given at the 32nd IBBY World Congress Santiago de Compostela 2010. http://www.ibby.org/subnavigation/archives/ibby-congresses/congress-2010/detailed-programme-and-speeches/evelyn-arizpe/. Accessed 20 Dec 2019.

Botelho, Maria José, and Kabakow Rudman, Masha. (2009) Critical Multicultural Analysis of Children’s Literature; Mirrors, Windows, and Doors. Routledge.

Bradford, Clare. (2007) Unsettling narratives: Postcolonial readings of children’s literature. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Chaudri, Amina & Teale, William H. (2013.) “Stories of multiracial experiences in literature for children, ages 9–14.” Children’s Literature in Education 44. 359–376.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. (1991) “Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color.” Stanford Law Review. Vol 43, no. 6. 1241–1299.

Dudek, Debra. (2011) “Multicultural.” Keywords for Children’s Literature, edited by Philip Nel and Lissa Paul, New York University Press. 155–160.

Heikkilä-Halttunen, Päivi. (2013) Lasten kuvakirjojen pitkä tie tasa-arvoisiin esitystapoihin. In: Rastas A (ed.) Kaikille lapsille: Lastenkirjallisuus liikkuvassa, monikulttuurisessa maailmassa. Helsinki, Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura: 27–61.

Hope, Julia. (2017). Children’s Literature About Refugees: A Catalyst in the Classroom. UCL Institute of Education Press.

Kontio, Tomi. (2015) Koira nimeltään Kissa. (Illustration Elina Warsta). Teos.

Kontio, Tomi. (2019) Koira nimeltään Kissa tapaa kissan. (Illustration Elina Warsta). Teos.

Kummu, Essi. (2012) Puhelias Elias. (Illustration Marika Maijala). Tammi.

Kummu, Essi. (2015) Puhelias Elias – Harjoituspusuja. (Illustration Marika Maijala). Tammi.

Kummu, Essi. (2019) Puhelias Elias – Häätanssit. (Illustration Marika Maijala). Tammi.

Lestelä, Johanna. (2019) Tuikun tärkeä tehtävä. Otava.

Marttinen, Tittamari. (2014). Ikioma perheeni. (Illustration Aiju Salminen). Pieni Karhu.

Meek, Margaret. (2001). “Preface”. In Margaret Meek (ed.) Children’s literature and national identity. Trentham Books: vii–xvii.

Nel, Philip.(2018). “Migration, Refugees, and Diaspora in Children’s Literature”. Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 4. 357–362.

Oikarinen-Jabai, Helena. (2009) “Mona’s and Sona’s imagined landscapes”. In Barbara Drillsma-Milgrom & Leena Kirstinä (eds) Metamorphoses in children’s literature. Enostone. 131–143.

Pelliccioni, Sanna. (2018) Meidän piti lähteä. S&S.

Pesonen, Jaana. (2015) Multiculturalism as a Challenge in Contemporary Finnish Picturebooks: Reimagining Sociocultural Categories. University of Oulu.

Pesonen, Jaana. (2019). “Children’s storybooks supporting the development of critical literacy and intercultural understanding”. In Jo Kelli Kerry-Moran & Juli-Anna Aerila (eds) The Strength of Story in Early Childhood Development: Diverse Contexts Across Domains. Springer.

Pesonen, Jaana. (2020).”‘We Had to Leave ‘and the problematics of voicing the refugee experience in a wordless picturebook.” Barnboken – Journal of Children’s Literature Research. (forthcoming)

Rastas, Anna. (2013). “Alille, Ainolle, Fatimalle ja Villelle: Suomalainen lapsilukija afrikkalaisten diasporasta.” In Anna Rastas (ed.) Kaikille lapsille: Lastenkirjallisuus liikkuvassa, monikulttuurisessa maailmassa. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura: 83–114.

Stephens, John. (2011). “Schemas and scripts: Cognitive instruments and the representation of cultural diversity in children’s literature.” In Kerry Mallan & Clare Bradford C (eds) Contemporary children’s literature and film: Engaging with theory. London, Palgrave Macmillan: 12–35

Tapola, Katri. (2020). Siinä sinä olet. (Arabic translation Aya Chalabee; illustration Muhaned Durubi.) Teos.

Vassiloudi, Vassiliki. (2019). “International and Local Relief Organizations and the Promotion of Children’s and Young Adult Refugee Narratives” Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature, vol. 57, no. 2. 35–49.

Yuval-Davies, Nira. (2006). “Intersectionality and feminist politics.” European Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol 13, no. 3. 193–209.

Österlund,Mia, Lassén-Seger, Maria & Franck, Mia. (2011). “‘Glokal’ litteraturhistoria: På väg mot en omvärdering av finlandssvensk barnlitteratur.” Barnboken – Journal of Children’s Literature Research. Vol 34, no. 1. 60–71.

The article was first published in German in Jahrbuch für finnisch-deutsche Literaturbeziehungen Nr. 52/2020.