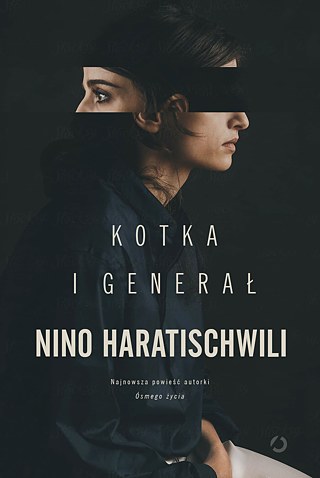

Interview: Author Nino Haratischwili

I Am Not a Mascot of Georgia

Should writers who reside in Germany but come from other countries, write only about “their” countries to be authentic? What’s the difference between writing a novel and writing a theatre play? Nino Haratischvili talks about all of the above and about her latest book, The Cat and the General.

You are known primarily as a writer of Georgian origins and the author of the bestselling "The Eighth Life". But you trained to be a theatre director and your first pieces of writing were theatre plays written in German. How did you end up writing in a foreign language?

Nino Haratischvili: Back in Georgia I went to a German school. Not all subjects were taught in German, but it was the teachers’ mother tongue. Already at that time I had started a theatre group in Tbilisi and the teachers encouraged me to write. My first opportunity to write a play arose from an exchange with a theatre group from Bremen. I was fifteen at the time and had no clue about writing for theatre, but I gave it a try and I really liked it. The following year we were invited to Bremen and I wrote another play. Again, I enjoyed it – the experience of writing something and then watching it come to life. Around the time of my A level exams it became clear what I wanted to do in life. I moved to Hamburg to study theatre directing. Two years into my studies we were given the opportunity to direct a play for a large audience. I was determined to stage my own play and decided to write it in German. It worked! In a way, I got into theatre through writing.

And nowadays, do you feel more like a theatre director or a writer?

Both - despite the fact that people view me more as a writer. Recently I may have had less to do with theatre directing, but I can’t imagine giving it up. Writing is a completely different process. You sit there on your own and you need to make all the decisions yourself. Theatre means working with a team. It’s a luxury for me to be able to combine directing and writing.

I have heard many critical voices saying that my plays are too emotional. (...) On the other hand I have never met a theatregoer or a reader who’s told me that they weren’t moved by the particular story being told.

Good question! Since I came to Germany, I’ve been fighting to be allowed to tell stories in the way that I feel I must. Of course intellectual aspects are important, but emotional ones matter even more. And it’s true that this is not something that is popular nowadays in Germany. I have heard many critical voices saying that my plays are too emotional. That applies to my books as well. On the other hand I have never met a theatregoer or a reader who’s told me that they weren’t moved by the particular story being told. For me this proves that the prefix ‘post’, which you mentioned, only exists in the experts’ discourse. It’s art for art’s sake. I’m fighting against that. People love the epic - especially nowadays. This is reflected in people’s preoccupation with TV series, with Netflix for example. Viewers want to be stimulated not just on an intellectual level. I think that purely intellectual theatre excludes much of the audience. It’s become even more elitist, and I have a problem with that. Going back to your question – it’s not easy but this fight is worth fighting on every level. Who do I write books or theatre plays for? I don’t do it for the critics or intellectual elites.

In one of your interviews you mentioned that the German theatre is rather inaccessible to foreigners, that the actors are mainly native Germans. This stems from a strong tradition of spoken theatre in Germany. However in literature, writers of non-German origin are playing an increasingly important role. You are part of this trend. Do you read other non-German writers who, like you, write in German about the stories and history of their countries of origin?

Yes, of course, I read pretty much all of them, from Katya Petrowskaja, to Olga Grjasnowa and Saša Stanišić. They all bring their own individual traits: their themes and specific languages. However this kind of writing causes controversy, which also applies to me. Whenever we go beyond the thematic circle linked to our countries of origin, we are criticised. For example Saša Stanišić, who is from Bosnia, wrote a novel set in the German region of Uckermark. The Germans attacked him for doing this, instead of focusing on his native Bosnia and the war. We are expected to only write about “our” countries, because this, supposedly, is authentic. It happens to me too. I am criticised for writing about Chechnya in my new book. After all, I know nothing about it. These are incredibly limiting and unfounded accusations. And the very concept of “authenticity”, repeated endlessly by the critics, is a complicated issue.

As exotic as the subject of The Eighth Life! I don’t think that national themes are a problem for literature. If a book is good, then I don’t care if the storyline takes place in Alaska or in Germany.

Do you think it’s easier for artists with non-German origins to be productive in Germany?

It depends on the particular context. Sure, if somebody happens to be in vogue and fulfils expectations, for example by perpetually writing about their origins, it can be like that. But first you need to get noticed. That didn’t happen in my case - I didn’t have it any easier just because I came from a different country. But I also didn’t knock on one door after another, advertising myself.

But you still get asked about your Georgian roots in pretty much every interview. Aren’t you tired of the questions about Georgia? Are you proud of being viewed as an ambassador of your country or does it annoy you?

Both! Of course I’m very happy that Georgia has become a focus of interest which people then visit on holiday and read books about. I was happy that Georgia was the Guest of Honour at the 2018 Frankfurt Book Fair. But, quite naturally, it also annoys me. I can’t represent the whole country. It always depends on the context. When I feel that my involvement might be useful, for example through translation or helping other authors, then that’s a good thing. But when I’m expected to represent Georgia or show it to others, I try to get out of it. I am not a mascot of Georgia.

When I feel that my involvement might be useful, (...) then that’s a good thing. But when I’m expected to represent Georgia or show it to others, I try to get out of it.

I think people need to find a reason for somebody with a different mother tongue to write in German. I don’t know if I distance myself. I live in Germany, I always wanted to tell stories, and so I do it in German. Otherwise I would need to have them translated into German. And German isn’t my mother tongue. Each phrase is coloured with the Georgian language and that will never change. Which doesn’t mean I have the perspective of an observer, but I do have fun with experimenting. When you use your mother tongue, you do everything automatically. When I use German I ask myself, why this way? Why this article? Why do I need to use a phrase in this particular way and not the other? It’s hard, but I’ve always enjoyed experimenting. In this sense the term “distance” might be quite fitting.

In "The Cat and the General" you tell the story of a Russian soldier who, years after the war, wants to reconstruct a war crime committed in Chechnya to repent for his sins. While doing research for the book you spent ten days in Chechnya. What type of research did you do?

It wasn’t research similar to that which I did for The Eighth Life, when I spent months in libraries and archives. This wasn’t possible in Chechnya. Everything has been erased. In the public perception there were no wars. It was important for me to gain impressions: what kind of country is it, what kind of people live there, how does it look, what’s the nature like, what kind of traces have been left by the past. In the history museum of Chechnya the exhibition ends with the Second World War. There is nothing after that.

And the people? Don’t they talk about the war?

Yes they do, but very quickly you notice boundaries. You can sense fear. Of course if you were to spend more time with them, they would tell you more, and would even sprinkle their stories with humour. I think that some try to play down their situation in this way, but not everyone.

A motif running through your creative output contrasts the Eastern Bloc countries perception of history with that of Western discourse. For example the story of the collapse of the Soviet Union is different when told from the viewpoint of a German and that of a Georgian, Russian or Pole. This also is a theme of "The Cat and the General". Where does this stem from? And is it at all possible to make it objective, to connect those two different perspectives?

That’s a good question. I don’t think you can be totally objective in any sphere of life. Facts are sometimes also just a question of a person’s viewpoint. We are always dealing with an interpretation. But you can still try. At some point it became clear to me that after years spent in Germany my perception of history and my knowledge of the 20th century are more informed by the West. I knew more about the Nazis than I did about the Communists. And at school I learned more about the Middle Ages in Georgia than about Perestroika. This was my biggest motivation and something I wanted to understand, regardless of the book I was writing. For me these were separate pieces of a puzzle. So at first it was a purely selfish motivation. When I started editing the book, I was very glad to hear from my editor, ‘Ah, I didn’t know this; I didn’t know that’. For example Mikhail Gorbachev is perceived completely differently in the East to how he is regarded in the West. Here they see him as a hero who did something good. In Georgia or Russia this is not the case, and probably also in Poland.

Do you have an idea for a new novel or a theatre play?

Yes, I have ideas, but I’m still far from realising them. It’s wonderful that my new book is attracting so much interest, but at the same time I find it more and more difficult to focus on something which is fundamental.

Then for the future I wish you the time and peace for discovering the fundamental!