In Germany, many doors close before a window opens. I see living here as a phase of my life, with a clear beginning and an uncertain end. A personal essay by Tuareg artist Moussa Mbarek.

“Throw it behind you, and you’ll see it in front of you.” German translations rarely capture the true meaning of proverbs in another language. In Tuareg, this proverb roughly means: Help someone now, and they’ll help you later.No, I don’t feel that anyone here thinks that way. I speak Tamasheq, and in this language lies my identity. It’s the language that unites and connects us Tuareg people—and in the diaspora I’ve truly discovered the strength of this bond. When I explain our culture to people in Germany, I feel it more than ever. I’m always looking for people who speak my language; even Arabic can’t ease this longing. Often, there are no words to express things from my culture. Where words are lacking, art steps in. That’s why I support human rights movements among our people in my old homeland, Libya, through my artistic contributions.

My Roots are Severed

Nearly 10 years ago, I fled Libya. Since then, I have lived, by chance, in Germany. I had two options: die in the war in the south, or drown in the sea in the north. Like many others, I took the route by sea to Italy. But Italy didn’t want me. I had to leave the country within 10 days, like a parcel in the post. Unwanted mail. So my journey led me to Germany.I come from Ubari, in southwestern Libya.

I was born into a nomadic Tuareg family, and was therefore stateless. In the 1960s, Libya’s leader Muammar Gaddafi offered citizenship to the Tuareg on the condition that they embrace Arab nationalism—but my family refused. For them, losing their Tuareg identity and assimilating culturally and politically was unbearable. That decision shapes my life to this day: no nationality, no passport, no identity.

My goal was always to study. But while I wanted to become an engineer or study art, my origins stood in the way. My parents’ decision closed many doors, because anyone without a passport is treated as a second-class citizen throughout their lives, even in their own country. This meant it was impossible for me to study or travel. After school, I could only work as an unskilled laborer, in car repair shops or in logistics.

The conflicts in Libya made normal life unbearable: you could be shot at any moment by warring militias, and your paycheck wasn’t enough to survive on. The images in my head became even darker. After spending time in prison, the day came when I realized I had to leave my homeland, which didn’t offer me a future. I had no specific goal, other than the desire to cling to hope.

When I arrived in Germany, I had no identity, I didn’t have a passport. So even more doors closed in front of me. Most of the laws that apply to us refugees require a valid personal identity document. Without it, you can’t open a bank account, get a job, or get married in Germany. Having an identity means having a passport.

Without a passport, you are considered stateless. Everyone who does has a passport should keep it safe: It defines you as a human being according to the laws of the world. It protects you.

Years of Struggling to Obtain a Passport

The biggest problems here are related to my legal status and to German bureaucracy. I would advise anyone considering fleeing their country to take all their paperwork with them, and to try to learn some of the language before they arrive. Living in a country like Germany is safe, and everyone enjoys the same rights, but that only happens if you are officially recognized.The important things are to find work and speak German. Racism exists, and you can feel it, but it’s not life-threatening, yet. To combat it, I also work for the association Zeugen der Flucht (Witnesses of the Escape), which runs anti-racist educational activities. We organize school visits and days dedicated to projects, to meet young people directly and engage in dialogue.

In Germany, associations are a good place to get to know people. I had to learn this, too, because nothing like them existed in Libya. Through associations, you meet people with similar problems, and you feel understood. You can forget your worries for a while, and have an impact.

That said, I can’t say I’ve actually built a network for myself. There are many people I can turn to, who help me when I need it. I’ve been lucky to get to know many people in Dresden, and they’ve given me the sense that I can belong among them. When you’re a stranger in a new country, you need support and help from the people who live there.

But this is not a real network, because I lack the language. Unfortunately, many of my compatriots have left Germany again, because they failed in the face of bureaucratic obstacles. I also need people from my own country around me, in order to feel at home.

Yet it’s important not to live in the past, so I’ve learned German. I also want, somehow, to achieve something; I haven’t been recognized as a refugee, but perhaps I will, after years of struggle as a stateless person.

However, after nearly 10 years, I can’t say that I’ll ever put down my roots here. The ground is still dry. Perhaps the rain will come, so I can stay here and grow branches, leaves, and flowers.

More than a Thousand Words

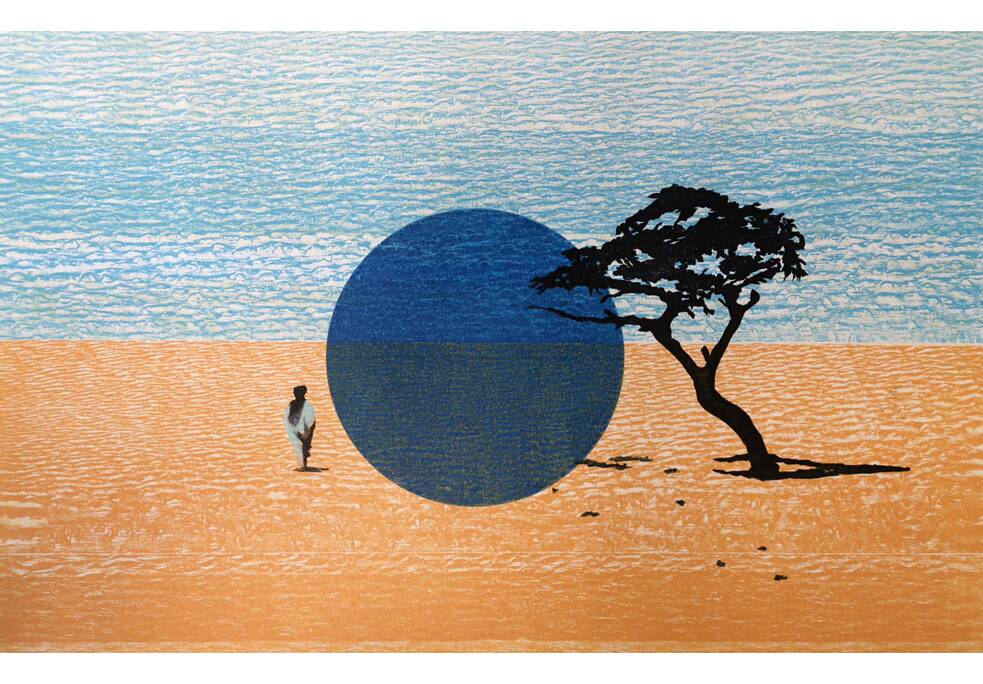

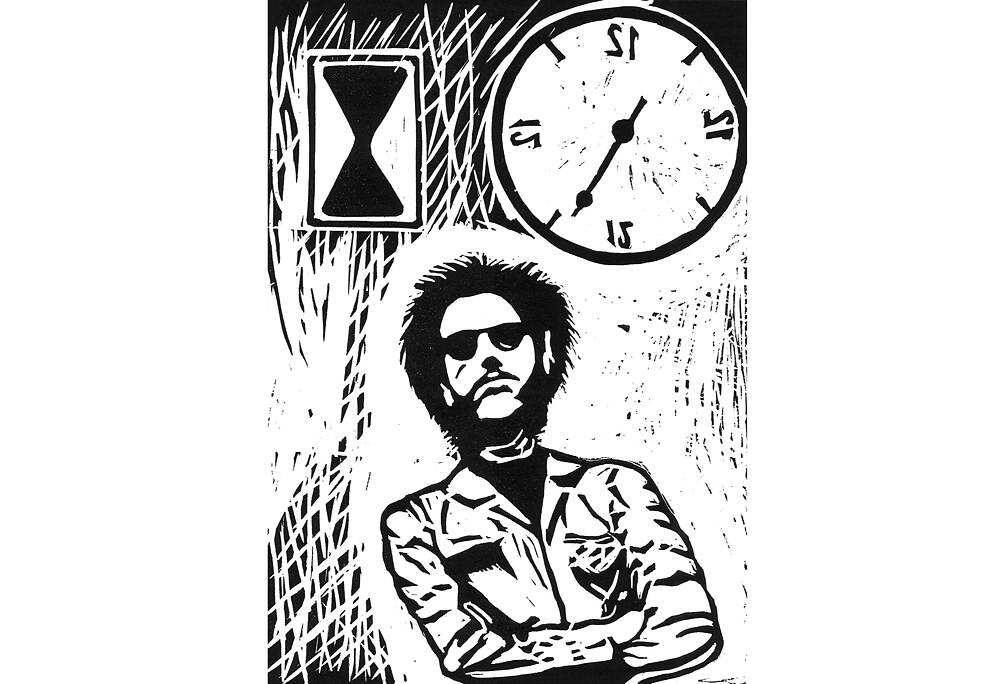

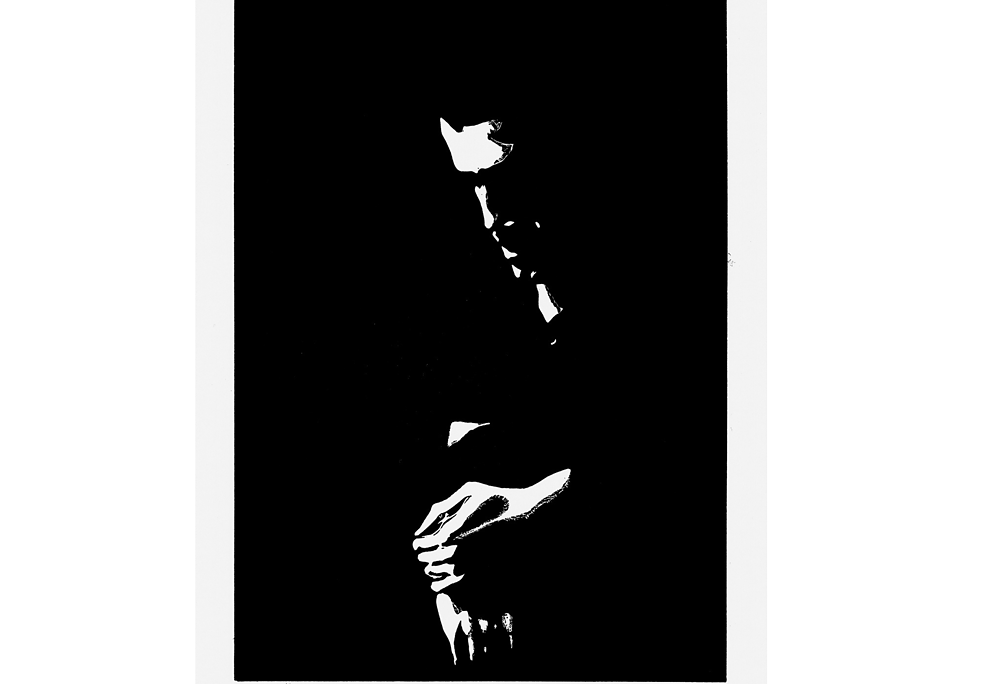

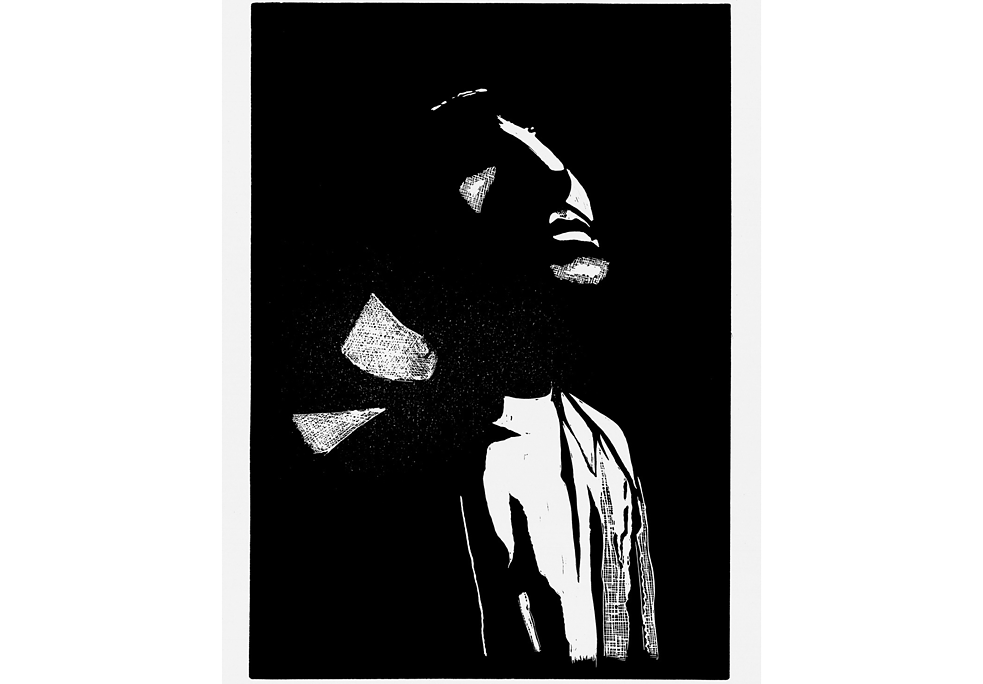

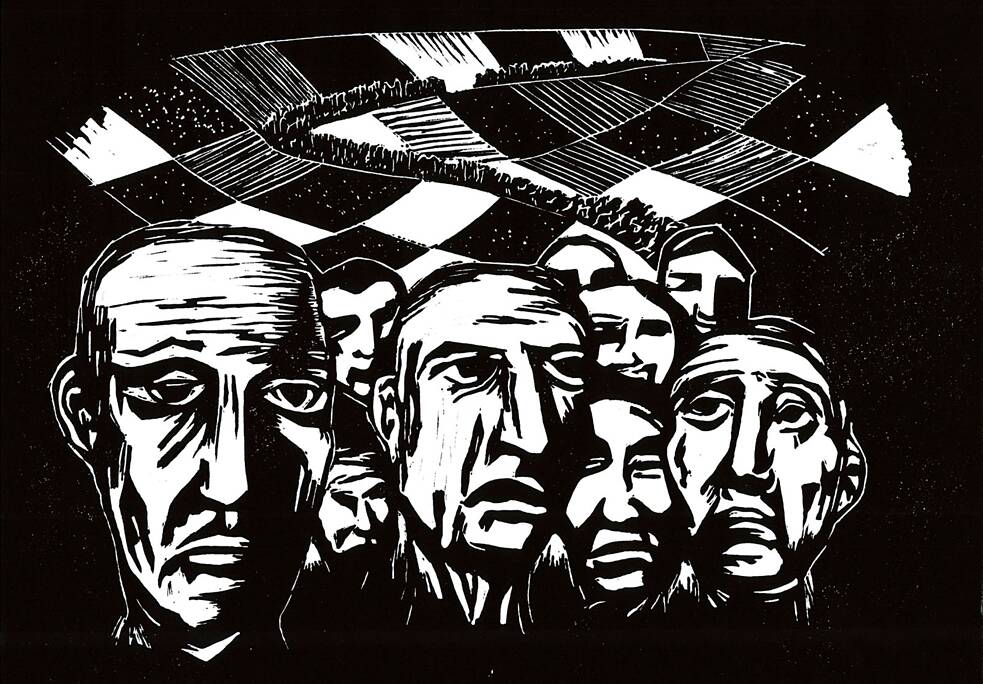

I want to continue along my path and spare others the same fate, so I began putting the thoughts and images in my mind down on paper. The language of images is understood without words, so it’s my tool for expressing myself and communicating with others.In the spring of 2019, I was fortunate enough to study as a visiting student in the department of Theatre Sculpture at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts.

Here, I took advantage of the opportunities to learn new artistic techniques, such as ink drawing and sculpture, and I enjoyed the clarity of engraving on wood and linoleum. I created images that could be understood across languages and cultures. Of course, I still have worries and fears, but art has helped me alleviate them.

The experience of what can be said with images, when one doesn’t yet have words, is priceless. Young children and elderly people can see things they never knew before.

Art has been a constant companion throughout my life, but I never imagined that it could have such a powerful impact. It has opened doors for me here, and become a means of exposing political injustices and making them understandable.

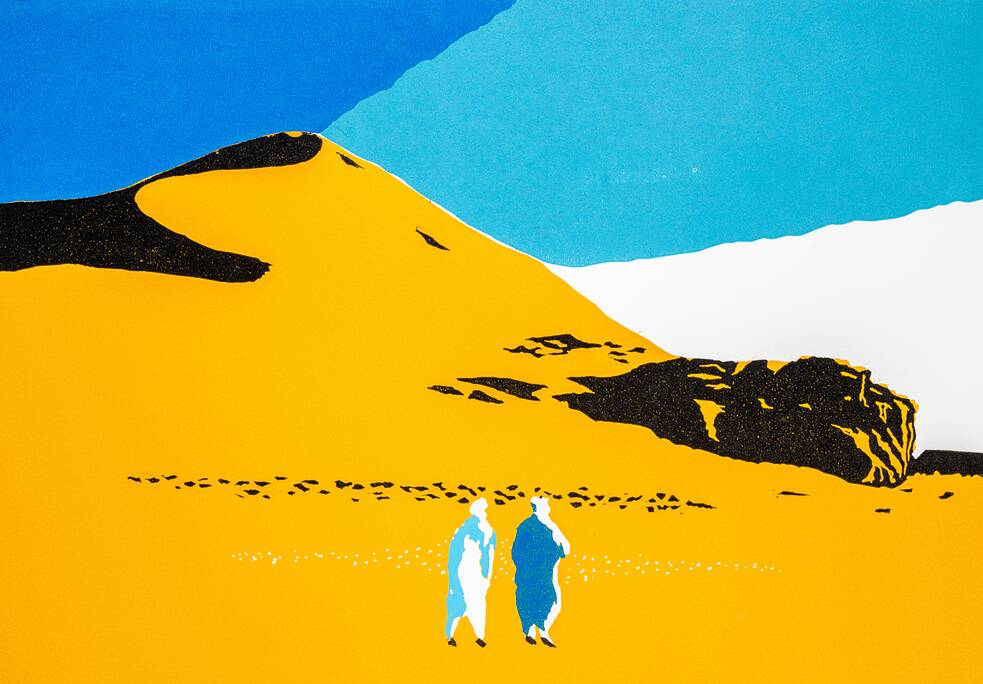

I have finally found a language everyone can understand. There are the pain and injustice that sometimes won’t let me relax, but there is also the desert: the yellow of the dunes, the blue of the sky, and the whiteness of the morning sun. All of this is present in my colorful paintings. They are a tribute to our culture, to what existed long ago, and to what will transcend contemporary politics.

Culture and Empathy Above All

What always amazes me is the ignorance of people here. When they hear that you come from Africa, they ask if you’ve seen giraffes and lions. Africa is a rich and diverse continent, made up of 54 countries, more than 2,000 languages, and over 3,000 ethnic groups—but here, they only understand a stereotype, far removed from reality. Another thing I don’t understand is this condescension towards us. We are all human beings, and all human beings are equal in value.Generally speaking, people here have no real understanding of the reasons why we left our homeland. The question remains for me:

What creates a person’s value?

For me, the answer is this: a person’s value lies in what he searches for.

October 2025