More than a century after the great Lebanese migration to Latin America, descendant families continue to search for their roots. This is the story of one of them: a journey through family memory, inherited myths, and a reunion with their homeland.

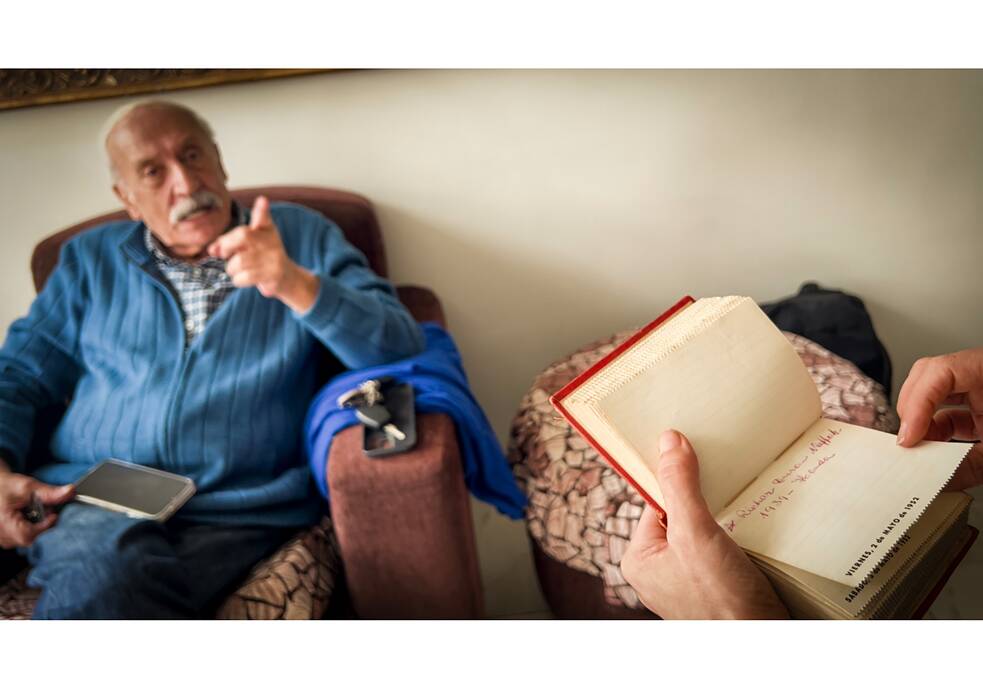

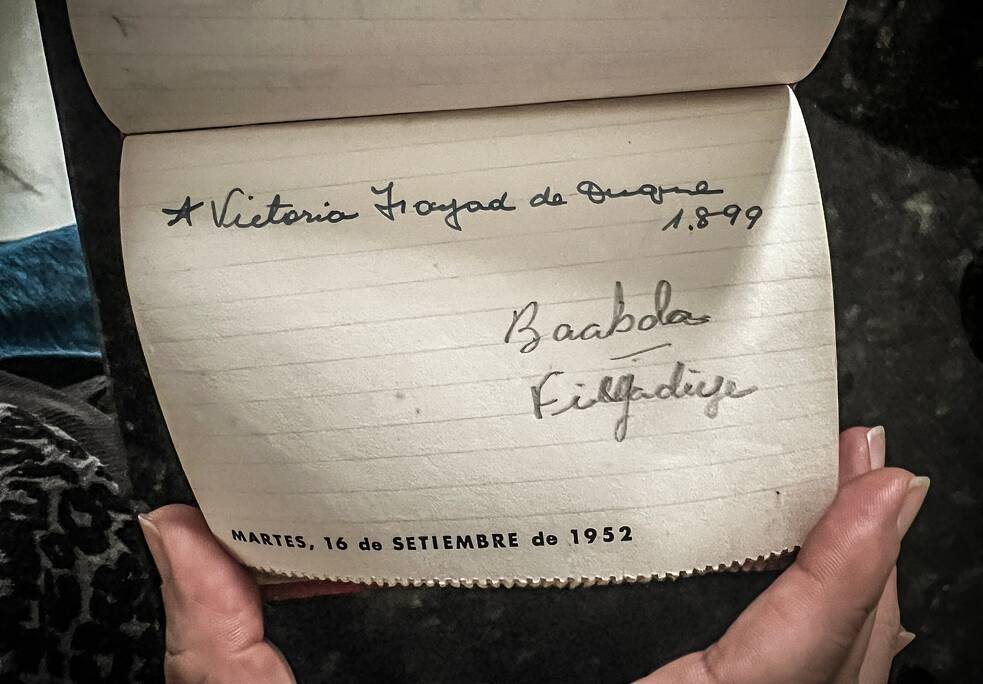

For decades, Lebanon remained an incomplete image in my father's mind. Not a country he could remember, but an abstract construction, made from memories constructed based on anecdotes about places and people that he, his brother, and his sisters heard from their relatives. A territory woven from fragments and partial versions. My father had never been there, but he knew Lebanon as one knows family myths passed down from generation to generation.In the family home, my father and his siblings were always surrounded by vestiges of that place that complemented their memories: a trunk with Darwich Fayad's initials, a walking stick with inscriptions engraved on it, sepia-toned photographs, a pair of tortoiseshell binoculars, a small red journal where my grandfather recorded the births of relatives. Also a tawle board with ivory dice. These objects had crossed the Atlantic at the end of the 19th century along with our ancestors, who had arrived in Barranquilla, on Colombia's Caribbean coast, and in the first half of the 20th century, they traveled down the Magdalena River to the bustling port cities of Lorica and Honda. They would later reach cities in the interior of Colombia such as Facatativá, where my grandmother Fadua was born, and Bogotá, where the family settled.

The “Turks” of the Colombian Caribbean

Until around 1920, many families sought new opportunities in the Americas. For many, their final destination was the United States of America, but they disembarked in the sweltering Caribbean sea of Barranquilla and other South American ports such as São Paulo and Buenos Aires. It is unclear whether these disembarks occurred by mistake, due to linguistic misunderstandings, because the transporters deceived them, or because they ran out of money to continue the journey.They were called “Turks” because the new arrivals had Ottoman Empire passports. But it wasn't just their nationality that changed upon arrival in Colombia; their first and last names also changed. Daaibes became Devis; Al-Khoury became Aljure; Abdur became Eduardo. Whether their names changed to facilitate assimilation or whether it was changed by an immigration officer who didn't understand the original pronunciation, we don't know.

The city of Bsharri in Lebanon was one of the places from which Maronite families left for the Americas. | ©Private

Lebanon: A Country Scattered Around the World

In 2016, my father, Ramón Fayad, received an invitation to a conference in Beirut. The event brought together members of the diaspora—presumably four times larger than Lebanon's population—who were prominent in their fields. In my father's case, it was science and education. My mother, Isabel, and I decided to travel with him. My sister Fadua, named after my aunt and grandmother, couldn't join us. During that trip, I saw my father set foot in Lebanon for the first time, at 68 years old.During that trip, I witnessed how the stories, anecdotes, myths, and geographical references heard for decades took shape before my father's eyes. Of course, we visited Baabda. We didn't mention the slight disappointment of seeing checkpoints and government buildings instead of the romanticized, 19th-century rural village we had hoped to imagine. We were moved to tears on those streets where distant cousins still lived, where grandparents had walked, and when we found the place where they were married before sailing to the Americas. My father imagined their nostalgia as they packed up their furniture and bid farewell to their homeland forever.

Memory under construction

Documentation in Colombia is fragmented. Existing publications generally have an anecdotal tone or are academic theses, rather than historical books for popularization or reference.

Novelist Luis Fayad, author of The Fall of the Cardinal Points, in his studio in Berlin. | ©Private

History has been repeated thousands of times. In Colombia, but also in Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico. The landings marked new beginnings, and the experience of exile has continued to transform itself in the memories, gestures, food, and faces of the generations who seek to trace, or understand, fragments of our own origins.

[1] Kebbe is a traditional Lebanese dish made from bulgur wheat and minced meat, and arepa is a traditional flatbread from Venezuela and Colombia made from semolina or corn flour.

This article was produced in collaboration with Humboldt, the regional magazine of the Goethe-Institut in South America.

October 2025