Bicultural Urbanite Brianna

Becoming Bilingual

I’m often asked why I started learning German. My go-to answer is “because it’s easier than French and Chinese”, both of which I tried and failed to learn at high school. German was still a hard slog, but I was able to gradually piece things together. I suppose I was drawn to its inherent logic and the satisfaction I derived from cracking the German code. I’ve built my career around being bilingual, yet in my day-to-day life in Berlin, there’s certainly still scope for crossed wires.

French and Chinese were compulsory in my first two years of high school. While I made some headway with French, I struggled to reconcile the disconnect between the way the words looked on paper and how they were pronounced. I couldn’t get a firm grip on all those slippery silent letters. Chinese, on the other hand, was a write-off. Sure, using calligraphy brushes to copy Chinese characters was fun, but when the teacher made any attempt to explain some facet of grammar or teach us vocabulary, the class clowns and ratbags quickly became bored and started playing up. We went through three Chinese teachers in two years.

Despite my lack of real progress in either language, I leapt at the opportunity to start learning German in Year 9. I have no idea why. Maybe German simply appealed to me more than the other elective subjects on offer. Either way, it turned out to be a bloody good decision, as it meant that I inadvertently learnt the language that would later enable me to fully experience Europe’s ‘capital of cool’. German made sense. I loved the hard and fast pronunciation rules that mean that what you see is what you get. The linguistic roots it shares with English also meant there were also many words that are only a hop, skip and a jump away from my native vocabulary. German seemed more tangible, with words that could be assembled in a series of strictly defined ways. It was easier to build bridges (or indeed, Eselsbrücken) between English and German words.

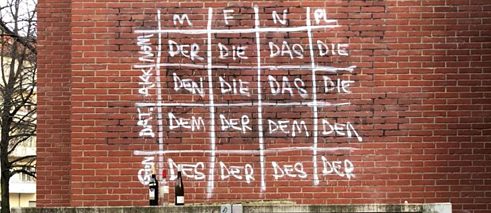

Seven Years Of Der, Die, Das

I spent seven years learning German during high school and university, yet by the time I moved to Berlin it felt as if my spoken German was still languishing in kindergarten. I had somehow managed to wing it until that point, relying on my good reading and writing skills. I understood virtually everything my German teachers said to me, but would respond with fairly monosyllabic answers. My classmates and I survived our VCE oral exams, thanks to an emergency phrase our German teacher taught us to whip out if we got stuck: “Ich habe nie daran gedacht” (I’ve never thought about it). I’m sure the examiners heard us parrot that sentence more than once as we each trundled into the examination room to trot out our carefully memorised scripts. House party circa 2003 with university friends from my German class.

| © Brianna Summers

After moving to Berlin, I spoke German every day at work and every evening with my flatmates. It took just three months before something clicked. Instead of translating everything in my head before I opened my mouth, I began simply expressing myself in my strange adopted tongue. I remember being utterly exhausted as my brain worked overtime, dredging up lost vocabulary from the depths of my memory and connecting new linguistic signifiers to objects, feelings and concepts.

House party circa 2003 with university friends from my German class.

| © Brianna Summers

After moving to Berlin, I spoke German every day at work and every evening with my flatmates. It took just three months before something clicked. Instead of translating everything in my head before I opened my mouth, I began simply expressing myself in my strange adopted tongue. I remember being utterly exhausted as my brain worked overtime, dredging up lost vocabulary from the depths of my memory and connecting new linguistic signifiers to objects, feelings and concepts.

Mix-Ups And Misinterpretion

There are many words and phrases that I continue to find odd and I still become entangled in linguistic misunderstandings from time to time. I find it troubling that the German word for ‘angry’ also means ‘evil’. So when I want to reassure someone that I’m not angry, I inevitably feel like I’m saying “I’m not evil”, which sounds ridiculous in my head. When I first heard the phrase “Ich gebe dir Bescheid” (I’ll let you know), I was working in a bookshop. “What the hell is a Bescheid?” I thought to myself, “and why is my supervisor going to give me one?” When a friend first signed off an SMS with “Ich melde mich” (I’ll be in touch), I thought she was planning to register herself for something. I knew the verb sich anmelden (to register), but had never heard of sich melden.And of course, the misunderstandings go both ways. Many years ago, I was sitting in the kitchen chatting with my flatmate when he suddenly became rather serious. He wanted to discuss the issue of hair clogging up the shower drain. I must have misunderstood what he said in German, because he switched to English: “Do you find it disturbing?” Much to his annoyance, I burst out laughing. To me, it sounded like he was asking whether I found the hairy blocked drain somehow alarming or creepy. Of course, he meant to ask whether it bothered me, ultimately with a view to requesting that I clean the drain sieve after I showered.

The kitchen at my old WG in Prenzlauer Berg.

| © Brianna Summers

Another memorable moment of miscommunication arose curtesy of the verb mögen, which means ‘to like’. My then boyfriend and I were at his parents’ house for dinner and his mother had cooked a lasagne that looked absolutely amazing. Just as we were sitting down to eat, she rushed up to me and asked “Magst du pierogi?” to which I responded “uhh…ja”. I was a bit baffled as to why she’d chosen that particular moment to enquire as to whether or not I liked pierogi, but sure, who doesn’t like Polish dumplings? She ran into the kitchen, I heard the microwave ping and when she joined us at the table, she had a plate of pierogi with her. It seemed unusual that she’d added a side of dumplings to the enormous, freshly baked lasagne steaming in front of us, but by this stage I was used to shrugging off strange customs so I didn’t give it any more thought. Only when I saw my boyfriend reluctantly stacking dumplings onto his already bulging plate did I realise what his mother had actually asked me. “Would you like some pierogi?” Dang.

The kitchen at my old WG in Prenzlauer Berg.

| © Brianna Summers

Another memorable moment of miscommunication arose curtesy of the verb mögen, which means ‘to like’. My then boyfriend and I were at his parents’ house for dinner and his mother had cooked a lasagne that looked absolutely amazing. Just as we were sitting down to eat, she rushed up to me and asked “Magst du pierogi?” to which I responded “uhh…ja”. I was a bit baffled as to why she’d chosen that particular moment to enquire as to whether or not I liked pierogi, but sure, who doesn’t like Polish dumplings? She ran into the kitchen, I heard the microwave ping and when she joined us at the table, she had a plate of pierogi with her. It seemed unusual that she’d added a side of dumplings to the enormous, freshly baked lasagne steaming in front of us, but by this stage I was used to shrugging off strange customs so I didn’t give it any more thought. Only when I saw my boyfriend reluctantly stacking dumplings onto his already bulging plate did I realise what his mother had actually asked me. “Would you like some pierogi?” Dang.Clearly, speaking a foreign language is always a work in progress.