Connecting the dots with bibi russell

Our editor meets one of her inspiring mentors to reflect on aspirations for a “good life” with the constraints of a finite planet and solidarity actions for Bangladesh’s crafts people that would continue to have impact beyond this pandemic.

By Mahenaz Chowdhury

The last time I wrote about Bangladesh and sustainability was precisely a year ago. Things were different. 2020 has been a long transition period in every possible way and continuing. How I used to conduct work, engage in conversations with people, and manage time for my family and self – it all changed. Maybe, it was because grieving had a new mechanism. It started off from a collective paranoia and fear of a rising death toll that didn’t matter more than just being numbers in newspapers. Then suddenly, those very numbers were people I once knew. It is strange to talk about people who were the defining part of my childhood, shaped me into who I am today, or had a lasting impact on my life, as just a number in the mortality census of the fiscal years of 2020-21. Is this what new-gen adulting means? To move on, flipping through pages in life, where everyone eventually is reflected as some sort of a statistic?

This can’t be it! Can we stop defining our lives as merely an economic indicator? We are more than just numbers! And this is why sustainability has never been more relevant and necessary in governance, education, politics, societal structure, and culture. It is not just a meager concept of going green and adopting carbon emission-reducing strategies to fight climate change, but it is the very essence of living a fulfilling and meaningful life.

With these thoughts keeping me up, my role in the world of sustainability, science, and art was starting to feel daunting. I was searching for a mentor to guide me through these transitions. And the stars aligned with Bibi Russell – the global guru of sustainable fashion, master recycler, and an incredible weaver. I was going to meet one of my most inspiring future mentors to learn about her work and an incredible initiative she has devised to mitigate the problems of this pandemic in the rural pockets of Bangladesh.

Bibi Russell (second from right) © Bibi Productions

Bibi Russell (second from right) © Bibi Productions

Hurrying out from the three-wheeler ride, masks on, sanitizer ready, I marched up the floors into the Bibi Productions studio. With a warm welcome, I was greeted into her office. Mesmerized by her cozy minimalist decor and a room filled with an aroma of soothing incense, I felt at ease already. She offered me tea. Served in her signature recycled glass, painted in rickshaw art (by an actual rickshaw artist!). Cha, biscuits, and art – the floor was all set! Little did I know that we would connect right off the bat, as she shared her philosophies of life and values with me. Bibi’s heart and soul in the fashion industry has been about one thing only: Revival and sustenance of the fine weaving heritage of Bangladesh. Her work has been focused around building and training remote communities to preserve our time-honored traditions. It was evident from our conversations, why she preferred spending all her time in the field – because that is where the magic happens! Exchanging experiences with the craftspeople and artisans, learning about their lives, and empowering them to be independent is what makes her work meaningful. With that, I was beginning to feel reassured about pursuing my aspirations in this field.

How did it all start for you?

“You know,” Bibi said, sitting across me on her couch, “I grew up in Old Dhaka in an environment that thrived on art and music. I remember being fascinated by the prints and colors of Gamcha (hand woven piece of cloth made out of cotton, used as a towel). I knew that I wanted to learn more about this craft and how it was made. I applied for the London College of Fashion in the 1970s and it wasn’t easy for me to get in. English wasn’t my first language and I had to work twice as hard than the rest to prove my worth and my skills. But I was determined to pursue my career in fashion designing and making a meaningful mark!” She then became the Face of Vogue, and went on putting Bangladesh on the map in her own way.

What was truly inspiring to hear was that in the midst of all this glamour, she saw the other side of the fashion industry from early on. During the budding industrializations of the 1990s, the world just learnt about fast fashion and mass production concepts coined by H&M. That’s when Bibi had a headstart on acknowledging the adverse impacts on the environment, depletion of resources, and the cultural erosion of our signature craft heritage to achieving competitive advantage over cheap labor. And it was the deciding factor for her to return to her roots and start Bibi Production – Fashion For Good. I could see her eyes lighting up as she said, “My heart belongs to the artisans. It is them who keep me alive and I always feel responsible for their wellbeing.” There was a brief pause. Bibi sighed, “The pandemic has been a real nightmare with reduced economic activity resulting in drastic drops in orders. They still smile warm heartedly and don't complain even though they are the worst hit in this situation.”

Didi Bosak is spinning 100% cotton yarn for the preparation to weave cotton saris in Tangail. © Bibi Productions

Didi Bosak is spinning 100% cotton yarn for the preparation to weave cotton saris in Tangail. © Bibi Productions

Creating work for her artisans and craftspeople has been imperative during this global crisis, because they need to survive. She declared her Call for Solidarity, “As we are passing through challenging and uncertain times and I strongly believe that it is only by joining our forces that we can effectively reduce the damages of the Covid-19 pandemic and its adverse socio-economic after-effects. Support and assistance would, no doubt, be required at many fronts and through multiple paths. My efforts are directed towards supporting the craftspeople, particularly the weavers, to assist them in working their way out of this emergency situation, to save their families, to protect their trade, and to preserve our age-old heritage,“ explained Bibi. “Because the hardest hit during this global crisis are the poorest and most vulnerable locals, who are from the low-income group, often self-employed or working in the informal sector, mostly working for small enterprises. These are the people predominantly excluded from public policies and are susceptible to being pushed into aggravating poverty, if we don’t act now!”

How can we help?

We can support the Call for Solidarity by purchasing Bibi’s solidarity bundle to ensure a steady income for the craftspeople. This will, in turn, allow them to sustain their work on handwoven fabrics, traditional arts, and cultural crafts. It has all the essential items we need during this pandemic and the best part is – it is made out of Gamcha.

Solidarity Bundle © Bibi Productions

The artists and artisans of Bibi Productions

Solidarity Bundle © Bibi Productions

The artists and artisans of Bibi ProductionsA personalized tour by Bibi entailed a colorful trip across the world of unique creations by her artisans. This has been one of the most humbling experiences for me to learn about the people, art, and authenticity Bibi upholds. From intricate crochet weavers in the remote areas of Saidpur to authentic rickshaw artists at her studio, she takes pride in the fact that each creation is true to its craft, that each person is recognized for their work.

With its mesmerising display of his freshly painted mini steel pots, Md. Saifuddin’ s painting den is a treat to the eyes. Painting for 18 years, one can truly say he is a master of this art form.

Md. Saifuddin – The Rickshaw Art Painter © Mahenaz Chowdhury

What do you love about being a rickshaw art painter?

Md. Saifuddin – The Rickshaw Art Painter © Mahenaz Chowdhury

What do you love about being a rickshaw art painter?“The feeling I get from creating my art. Every piece evokes a different feeling and that is priceless. I had known Bibi Apa for a while prior to the accident, she commissioned rickshaw painted products from me. After my accident, I lost the ability to walk as I lost one of my legs. Learning about my condition, Bibi Apa, offered me a space at her studio to commission work from me full time. It gave me the freedom to continue this art form.”

How can we differentiate between the work of an authentic rickshaw art painter and a copy artist?

With a smile he said, “It took me 18 years to get to where I am. There is math to it all. A big part of my work is to be able to repeat the designs and that is a very mindful process that I have been able to master over the years. The skills are evident in the strokes, alignment, colors, and composition once you start noticing. So, look closely next time when you are buying rickshaw art.”

What’s your take on the cultural appropriation of rickshaw art by the modern artists and businesses?

“The reality of rickshaw art by true rickshaw art painters is grim and exploited by the profiting businesses who don’t even hire real rickshaw artists anymore. The art sells in the name itself,” Saifuddin explained, as he dipped his brush in the water. The sorrow had sunk in his eyes. “Underpaid, unemployed, unappreciated. From 20 fellow artists in my original circle, there are only two of us still continuing to pursue this career in Dhaka. Fighting to keep it alive. Our younger generation is already uninterested in the demanding learning processes now coupled with the diminishing monetary future of the art nationwide. I hope businesses hire authentic artists to support them and their families and in turn protect the future of authentic rickshaw art.”

d. Saifuddin’s hand painted rickshaw art (upcycled bottles, jars, gallon) ` © Bibi ProductiMons

Exploring the world of Crochet with Bibi’s Protege

d. Saifuddin’s hand painted rickshaw art (upcycled bottles, jars, gallon) ` © Bibi ProductiMons

Exploring the world of Crochet with Bibi’s ProtegeNext Bibi introduced me to her protégé Nasrin (over the phone), one of her most talented crochet artisans from a remote area of Saidpur. An industrial area during East Pakistan days. After the liberation war in 1971, the “bihari” refugee camp was formed with people living in unimaginable conditions there. Bibi has established a working facility to support the poorest communities there by empowering them with skills training. A skilled crochet artisan from a very early age, Nasrin’s hopes and dreams of earning a living on her own is how she joined Bibi Production in the 2000s.

Nasrin – Crochet Artisan © Farah Khandaker

Nasrin – Crochet Artisan © Farah Khandaker

“One day, many years ago, the electricity went out at our office and I tried to fan Bibi with a taal pakha. But she immediately asked me to stop, emphasizing on how we are equals. I will never forget that. It's her humility that defines her. In twenty years of my experience, having met people from all classes and trades, no one is as down to earth as her.”

What is the most rewarding thing about your work at Bibi’s?

“Training other girls and empowering them to learn and earn. Being able to create jobs for these girls and the fact that I receive their blessings for it, this is what makes me the happiest.”

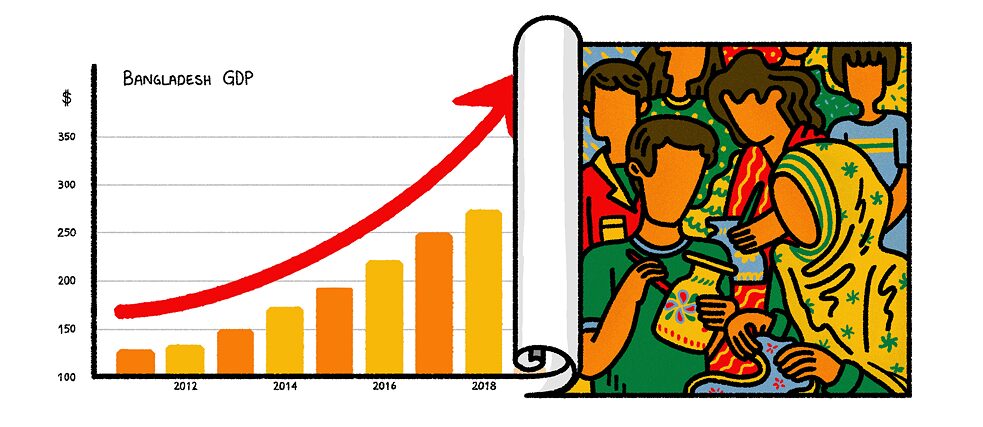

So, where do skilled and talented artisans like Nasrin and Saifuddin fit in the percentage of the GDP? Lost as a number in an industry, which is equivalent to a booming 34 billion dollar earnings accounting for 15-16% of our GDP. Even though it was in shambles during the first shock waves of the pandemic. The industry is recovering by 80% in the first quarter of fiscal 20-21, where we are foreseeing a GDP growth of 4.4% instead of 8% estimated by IMF. (The Financial Express, 2020) People like them are not even accounted for in the recovery package taken by the government to support the industrialists during this pandemic. Furthermore, they are not represented in the public policies either. It is true that if we do not have a healthy working class, we do not have a functional economy. But employment is just not enough! There needs to be inclusive governance, policies, structures, and public services accessible by everyone. Thus, we need a framework that considers a sustainable environment including the well-being of people, nature and improves the quality of life.

Quality of life is crucial for the sustenance of artisans and craftspeople © Farah Khandaker

Quality of life is crucial for the sustenance of artisans and craftspeople © Farah Khandaker

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mahenaz Chowdhury is a sustainability scientist, zero waste designer, and artist at Broqué. While obtaining a master’s in Environment Science & Management, she lives and creates in Dhaka. Mahenaz is a Local International graduate, a program funded by the German Federal Foreign Office.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

Farah Khandaker is an illustrator and designer whose repertoire work ranges from children’s book to editorial illustration. Farah published her first graphic novel with Bengal Publications and is currently working as a freelance illustrator. View her portfolio here.