Bauhaus Design

The Bauhaus is dead – long live the Bauhaus!

Is the Bauhaus still relevant? The Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein posed this question to sixty artists, designers and architects in advance of its Bauhaus exhibition. Their answers give some indication of the far-reaching importance of the Bauhaus to this day.

The response of the Milanese architect Benedetta Tagliabue went to the heart of the matter: “The Bauhaus is about an attitude, about a certain way of thinking and acting. And this has a great influence to this day.” The influence of the Bauhaus is in fact still immense and indisputable, and not only in design and architecture. Innumerable entries on the Internet, more than 4,500 publications on the Bauhaus, thousands of Wagenfeld lamps in the sitting rooms of the educated middle-class and at least as many plagiarisms of the lamp testify to this. Numerous exhibitions, such as that at the Art and Exhibition Hall in Bonn, on the second leg of its journey after its start at the Vitra Design Museum in southern Germany, also fuel the myth.

No single style

Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Tischlampe ME 1 /MT 9 (1923/1924)

| © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2016

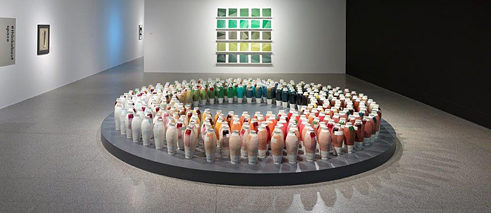

With exhibits from design, architecture, art, film and photography, the exhibition The Bauhaus. Everything is Design shows, true to its motto, that Bauhaus design has penetrated into almost all areas of life, ranging from the ashtray to housing. This was the declared goal of the architect Walter Gropius, who, borne by the spirit of change after the First World War, was in the mood for revolution. “Artists, let us topple the walls” was his rallying cry.

Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Tischlampe ME 1 /MT 9 (1923/1924)

| © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2016

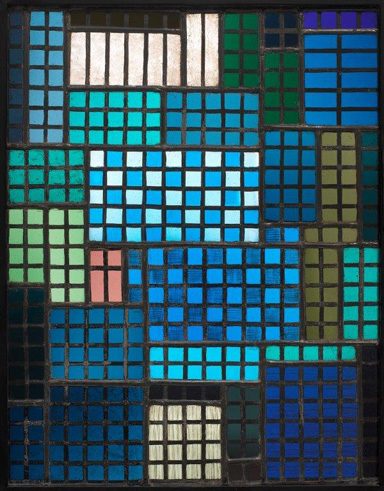

With exhibits from design, architecture, art, film and photography, the exhibition The Bauhaus. Everything is Design shows, true to its motto, that Bauhaus design has penetrated into almost all areas of life, ranging from the ashtray to housing. This was the declared goal of the architect Walter Gropius, who, borne by the spirit of change after the First World War, was in the mood for revolution. “Artists, let us topple the walls” was his rallying cry.Art and crafts were to merge and the future artists-craftsmen to join in the building of the new society. As apprentices and journeymen, they were trained in an unacademic and hands-on manner. Gropius also fetched already well-known artists such as Paul Klee, Vassily Kandinsky and Johannes Itten as teachers to Weimar, the first site of the Bauhaus. He himself became director of the new college, which under the name of the “State Bauhaus in Weimar” (Staatliches Bauhaus Weimar) started operation in 1919. Here, in the spirit of “productive disagreement”, as the Bauhaus master Josef Albers later noted, “masters” of crafts and visionary initiators came together, but not, as today is often assumed, to teach a uniform Bauhaus style. On the contrary, they showed that style is as multifarious as the individuals who create it.

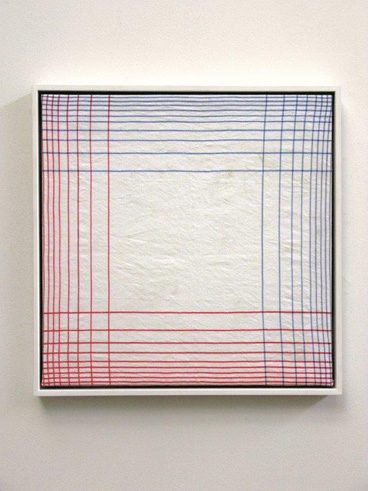

There were, however, terms of reference. Thus design was to be functional and adapted to use, affordable, durable and beautiful. “Form follows function” was the maxim that was to go down in art history. A famous example of it is the “cantilever chair” from 1926, designed by Mart Stam and developed by Marcel Breuer. In this tubular steel chair without back legs, whose seat gave resiliently under the weight of a person, almost all the paradigms were united. Only the price, owing to the initially low piece number, was comparatively high. Expensive too was the already mentioned Wilhelm Wagenfeld lamp, because it was hand-made. As its light cone was narrow, which made it rather unsuitable for reading, and its components were made of glass, it was considered neither practical nor particularly durable. But it was “beautiful” – a function that still makes it a coveted and, at around 400 euros a piece, exquisite design object.

Housing for all

That the Bauhaus was also a pioneer in social housing may be seen in the simple co-op interiors for inexpensive “people’s apartments” planned by Hannes Meyer, which were to be built collectively. A Marxist, the Swiss architect advocated “The needs of the people instead of the need for luxury”. Art should be only “a means for use”. In 1928 Meyer succeeded Gropius as director of the Bauhaus and, at its new location in Dessau, championed industrial production. His visionary principles, especially the search for maximum economy in form, materials and constructions, can be found again in modern housing ideas such as “sharing communities”, “open design” and “co-housing”.Source of inspiration

As a workshop for ideas, a “laboratory of modernism”, the Bauhaus has had its day. Not least because, in the face massive repressive measures taken by the Nazis, the institution, at which many Jewish masters taught, disbanded itself in 1933.Das Bauhaus. Alles ist Design – Behind the art – Exhibtion in the Bundeskunsthalle

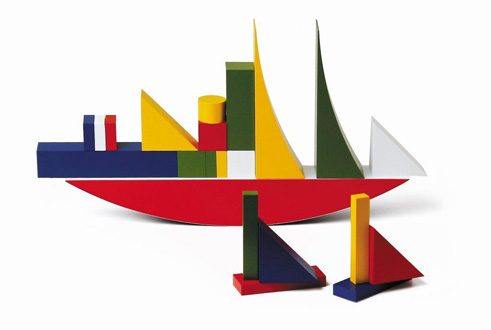

As a source of inspiration, however, many designers today still have recourse to Bauhaus ideas. In 2009, for instance, the Munich designer Konstantin Grcic created his “Pipe” chair based on the precursor model by Mies van der Rohe, the third director of the Bauhaus at its last location in Berlin. Or Joseph Grima, who has brought together Alma Buscher’s shipbuilding game, which was already a success in the 1920s, with the popular computer game Minecraft. As in the game with blocks, here the user can build his own virtual world. These are only a two examples from the 2016 exhibition that go to prove the ubiquitous presence of the Bauhaus. And only a foretaste of what awaits the visitor in 2019, when “100 Years of Bauhaus” will be celebrated everywhere.

After its station in Bonn, the exhibition “Das Bauhaus. Alles ist Design / The Bauhaus. Everything is Design” (01.04.–14.08.2016) will makes stops in Brussels and Tel Aviv.