Martin Luther

A Superstar with a Dark Side

The anniversary of the Reformation is coming up in 2017 and Martin Luther is the subject of much debate. Many fear that his story is going to be overembelished, with hardly any mention of his dark sides. Can you celebrate Luther and at the same time maintain a critical distance to him?

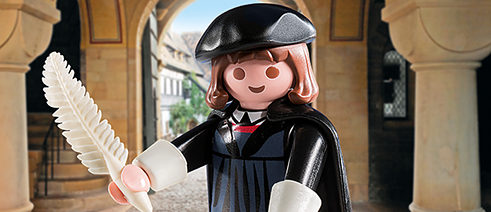

There is, of course, the Martin Luther who is a little more than seven centimetres tall and whose heart is made of plastic. In the one hand he is holding an open Bible, in the other a quill. This little model of the Reformer by Playmobil is a bestseller. Luther socks and Luther liqueur are also selling well. His likeness is also to be found on plates, cups and frisbees.

In 1517 Martin Luther (1483–1546) stuck his, then revolutionary, theses to the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg, for all to see. The Protestant church, the German Federal Government and several federal states are planning to celebrate the birth of the Reformation 500 years ago with numerous large events and exhibitions. It is all going to kick off on October 31st, 2016. While the whole hype around Luther is, on the one hand, becoming increasingly kitschy, some of his dark sides, on the other hand, are now beginning to emerge.

Can one, yes, should one actually celebrate Luther at all? This is the question being posed by journalists, historians and cultural scholars on the arts pages of newspapers, in magazines and books – thus voicing their criticism of the plans for the Reformation anniversary.

Agitation against Jews

Luther rebelled against the so-called selling of indulgences by the Catholic Church. The idea was for the faithful to pay money, so that their time in purgatory would be shortened. Luther argued, on the other hand, that every human being is loved and accepted by God anyway. There was no need to pay money for this, having a firm belief would be enough.This idea shook the very foundations of the church and led to many people emancipating themselves from the dogmas of the Popes. Luther's views, however, divided the church and plunged Europe into bloody religious wars. In addition, the Reformer stirred up hatred of Jews and Muslims. “Such a desperate, thoroughly evil, poisonous and devilish lot are these Jews,” he wrote, calling for the destruction of synagogues. His abhorrence of the Peasant Revolt also encouraged the princes to take brutal action against their subjects.

Back at the celebrations for the 400th anniversary of the Reformation nobody was interested at all in Luther's dark sides. He was regarded as a kind of national saint who went down in the history books with the Bible in his hand and assured of victory. His steadfastness against Pope and Emperor served as a model for the religious exaltation of the Germans' willingness to sacrifice themselves in World War I.

Many like the idea of him being a pioneer of democracy

Of all the things that were said and written back then, there is in fact quite a lot that the church, for good reason, still finds embarrassing today. When one looks back at the terror of the Nazis, the war and all the destruction, Luther as a German national hero seems out of place – and the church is fully in agreement about this with historians and politicians. But is it possible to celebrate Luther and at the same time to dissociate oneself from all the heroic and dark aspects?The Protestant church would like to present Luther in 2017 as a “powerful symbolic figure”, “who, like many great historical figures, provokes people to challenge, but, at the same time, with perseverance, boldness and conviction encourages them to identify”. The Reformation is to be depicted as a European “history of freedom”, which contributed to the development of the modern fundamental rights of religious freedom and freedom of conscience, changed the relationship between church and state and promoted the modern understanding of democracy. The German federal government and the prime ministers of the individual German states also like the idea of celebrating Luther as a pioneer of freedom, human rights and democracy. “Martin Luther Superstar” was the title of a publication for the anniversary by the German Cultural Council.

Destroying popular myths

For many historians this is going too far. Luther was not a pioneer of modern times, says Daniel Jütte, for example, from Harvard University, but “one of the last men of medieval times”. The freedom that Luther spoke of, had always been based on God and is not comparable to the secular freedom of Western societies today. Theologians also warn about smoothing over Luther's alienness so well that he does not cause a stir anymore. Historians and cultural scientists are also taking great pleasure in destroying popular myths. Apparently Luther did not nail his theses to the church door in Wittenberg, and a hammer was not used either, but sealing wax. It was not until the 19th century that Luther was depicted with a hammer in his hand, in the wake of him being stylised into a national hero.The warnings about not putting Luther on a pedestal again are justified. The medieval monk is not a contemporary of today. However, if one were to take into account all these concerns and apprehensions, there would only be enough material for a large congress for historians or theologians. That would really be too little for an event that actually changed Europe in a most profound way.

In these days of the 21st century, if one wants to convey historical events in a way that appeals to the masses, generalisations and a bit of hero worship have to be part of the show. Even the debates preceding the whole project are also necessary. They are not annoyingly disruptive tactics, as some church officials said, but the proper way for a modern democracy to deal with its past. No matter what, Luther would have loved the idea that people are still passionately arguing about him 500 years later.