Berlinale Bloggers 2019

An Australian Dynasty

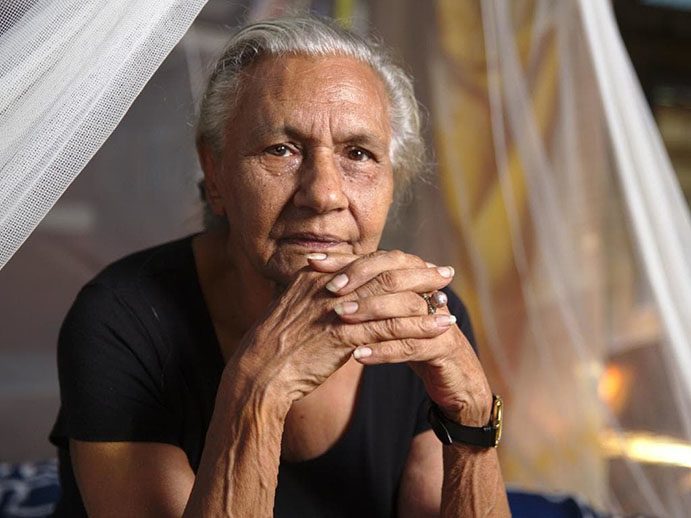

Without Freda Glynn, Australia’s Indigenous media landscape might look as parched as the country’s sunburnt earth. And yet, as ‘She Who Must Be Loved’ makes plain, she’d rather let her actions speak for themselves. Or, better yet, let the generation of filmmakers she has trained and raised do the talking — ideally about someone else.

By Sarah Ward

Across her career, Freda has fostered Indigenous talent across two of the nation’s crucial organisations. The Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association showcases Aboriginal music and culture, starting in 1980 as a radio station focused on and run by the Indigenous community, while Imparja Television extended the outfit’s remit in 1988. In her personal life, Freda has also played matriarch to a family of directors who are now shaping Australian filmmaking in the 21st century. Son Warwick Thornton has the acclaimed Samson & Delilah and Sweet Country to his name, grandson Dylan River is the helmer of documentaries Buckskin and Finke: There and Back, granddaughter Tanith Glynn-Maloney is carving out a producing career, and daughter Erica Glynn directed Black Comedy, produced Redfern Now and guides this tribute to her mother.

Celebration of a Trailblazer

As the above overview conveys, there’s much to the elder Glynn’s life — enough for several films. Hers is a tale not just of advocating to give Australia’s first peoples a voice, but of the impact of the nation’s historical treatment of its Indigenous inhabitants. And so the younger Glynn moulds She Who Must Be Loved into a celebration of a trailblazer, as well as a chronicle of the societal context that coloured her life. It’s also a document in the true sense of the word, capturing stories and details that demand recording, sharing and remembering. Freda Glynn. | © Kathryn Mills

Freda Glynn. | © Kathryn Mills