Keith Haring And Beyond

© Photo: TheDustyRebel

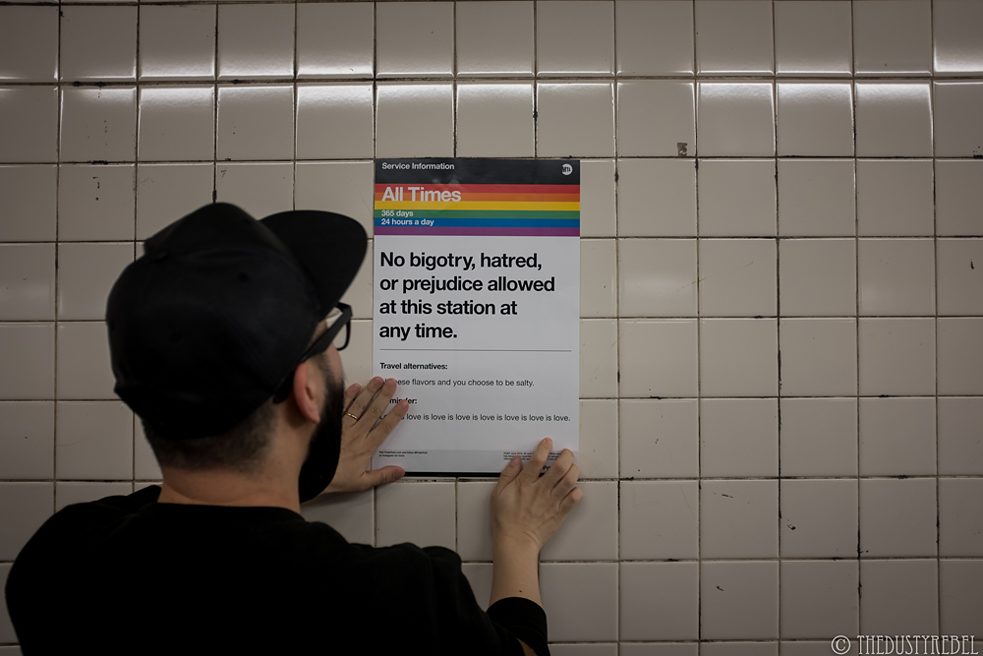

Daniel “Dusty” Albanese is the New York City-based photographer and filmmaker behind the website TheDustyRebel. Shaped by his background in anthropology, he has built a worldwide following documenting the more marginal aspects of the urban landscape, as well as controversial artworks, political protests, and city living. In 2017, he began production on his first feature length documentary and book exploring the global Queer Street Art movement.

By Katherine Lorimer

Art should be something that liberates your soul, provokes the imagination and encourages people to go further.

Keith Haring

After documenting NYC Street Art for a decade, what motivates and inspires you?

My work as a photographer is very much motivated by curiosity. I’m particularly interested in people who use public space for self-expression or push socio-political boundaries. What drew me to Street Art was the mystery of how it got there, who made it, and why. I was fascinated by this chorus of unique and subversive voices in the street.

Over the years I’ve noticed a decrease in meaningful Street Art, especially here in New York City. There's no doubt that social media has had a massive effect on it—great for spreading Street Art and creating a global community, but encourages work that's less subversive because of commercialization, censorship, and artists “performing” for followers. So many artists are creating work designed for social media, and placing it in hot spots where it’ll get Instagrammed. Now we’re seeing brands co-opting Street Art for marketing, exploiting artists to work for “exposure,” or creating ads to look like Street Art.

So instead I focus on what I find most interesting: Unique or politically-charged work, usually done without permission.

What role do identity politics play in Street Art?

Because of its subversive nature, I think it’s a natural for marginalized people to gravitate to Street Art. When you very rarely see yourself reflected in the mainstream culture, it’s the perfect medium for doing it yourself. Here’s a good example: I do an ad takeover series that feature my photographs called “Resistance Is Queer.” When they first went up, I was really moved by the messages I received from total strangers, who told me how much seeing them meant to them. There is such power in the simple act of transforming an ad into art that acknowledged the existence of those who are too often ignored. It really hit me. Every expression of queer existence is a revolutionary act.

Great potential as a political tool

What are common misconceptions about Queer Street Art?First off, I don’t think people are aware of just how much there is. Also, I think people often misunderstand the motivation of the artists. It's more than rainbows, or erotic just to be erotic. For example, Homo Riot and Jeremy Novy use aggressive, overtly homoerotic imagery as a political tool to make the viewer confront their own homophobia. EDES from Copenhagen explores “silent homophobia” and pushes the boundaries of homoerotic graffiti with explicit yet whimsical vignettes painted on public trains. Kashink in Paris deconstructs gender and aesthetic codes of beauty through her work. And Suriani, a Brazilian artist, explores gender expression with his vibrant life-size wheatpaste portraits of drag queens.

What can Street Art do for the LGBTQ community? What can the LGBTQ community do for Street Art?

Visibility, from both sides. It’s essential for minority groups to see themselves represented in art and culture. And quite frankly, many of the pioneers of what we would call Street Art, like Keith Haring, were queer. That history has been largely forgotten.

Street Art is a medium that has great potential as a political tool, and has been used as such for decades. Various political art collectives—such as Gran Fury, Fierce Pussy, QueenZofTheNight, and Pride Train—very effectively use public space to spread their messages.

One of the first steps for social change is consciousness raising. By becoming visible we assert our existence, and we can find each other. By finding each other we build a community. But it’s also important how we use visibility. For example, Gran Fury were very thoughtful in how they portrayed the AIDS epidemic. Their visuals avoided the individual suffering of the “AIDS victim”: a gay man wasting away and dying. Instead, they made conservative politicians, journalists, and Christian fundamentalists the face of the crisis. They used kiss-ins and images of queer people kissing as a public defiance of homosexual invisibility, and to force all those who see it to confront their own homophobia.

There’s a lot and it’s complicated

You are working on a full-length documentary on Queer Street Art. Why has it taken this long for Queer Street Art to achieve visibility and what do you hope people will take away from the film?That’s a good question because it’s what I’ve been asking myself since 2014 when I started this project. Street Art is more popular than ever, yet when I began my research on queer themed street art, there was very little to be found. This is why I built my own database, compiling every queer street artist I could find from around the world. Through word of mouth, combing the internet by relevant search terms, and surfing hashtags on every conceivable social media platform, I’ve compiled over 140 entries. 140! This really got me thinking. If there is such a rich history of queer street artists, a ravenous appetite for Street Art like never before, and social media tools to instantly document and connect the world, why does queer Street Art remain invisible?

There are lots of reasons, certainly more than we have time for here. But, I think it has to do with the dominant straight culture not seeing queer codes in our art, censorship, not enough queer people self-documenting, and a movement towards commercialized Street Art and murals which are less subversive. There’s a lot and it’s complicated.

As for what I hope people take away from the film? I want people to see how rich and diverse the queer Street Art scene is, and what an important role it’s played. I want to amplify and create a historical record of voices that deserve to be heard. I want to remind people of the important subversive power of Street Art.

Why does so much Queer Street Art get censored?

Many of the artists I've interviewed have experienced censorship both in the real world and social media. Often work on the street that’s overtly queer or that shows sexuality will be defaced faster or targeted more aggressively than non-queer art.

Censorship on social media is even worse. As much as we might not like it, social media has become a vital tool for communicating and building community. But when those platforms decide you don’t meet a vaguely described “community standard” and begin erasing you, that’s especially dangerous for marginalized communities. For example, Tumblr recently changed it’s policy and began purging “adult content,” which includes “female presenting nipples.” Think about that. We have social media platforms using some kind of algorithm to decide the gender of an individual, then attributing a level of erotism that needs to be censored onto one human’s body but not another’s. I know of dozens of queer and feminist artists who have had their accounts suspended. When @lgbt_history posted Zoe Leonard’s poem, "I want a president" on Instagram it was censored by the platform. Recently, when performance artist Carolee Schneemann died, posts paying tribute to her work were also removed from Instagram.

Cultural and artistic erasure by social media gets us into dangerous territory, which is why it’s all the more important that Queer Street Artists and their allies document and preserve the work for generations to come.

Tribute to Marsha P Johnson and queer liberation by artists Homo Riot and Suriani at Second Avenue and Houston Streets in NYC, curated by the Dusty Rebel as part of an alternative to corporate-sponsored Pride. Suriani’s imagine of Marsha is based on Richard Shupper’s studio portrait of Marsha P. Johnson from 1991, the year before her death. @rick_shupper

| © Homo Riot and Suriani Photo: TheDustyRebel

Tribute to Marsha P Johnson and queer liberation by artists Homo Riot and Suriani at Second Avenue and Houston Streets in NYC, curated by the Dusty Rebel as part of an alternative to corporate-sponsored Pride. Suriani’s imagine of Marsha is based on Richard Shupper’s studio portrait of Marsha P. Johnson from 1991, the year before her death. @rick_shupper

| © Homo Riot and Suriani Photo: TheDustyRebel