Alec Empire

“We can program the future for ourselves”

As an artist on the Francfurt label “Mille Plateaux”, Alec Empire and his band Atari Teenage Riot had a political perspective on Germany’s early techno scene.

Was there a moment that blew you away when hearing techno for the first time?

Alec Empire: There wasn’t a moment like that for me. And I can easily explain why that is: I was at my first acid house party in Nice in 1987. That was really pure acid house. Very straightforward and I got it immediately. I felt more on the outside of it though. So I didn't have that experience, which many often describe, that they got caught up in a party, in a club or at a rave and then got swept away. But it was immediately clear to me that this is the way out of a dead end that I felt with punk at that time. Before I was into punk and even made it myself with my band in the Berlin scene back then, I – like many later techno producers – had heard and liked the first rap stuff, Grandmaster Flash and so on. So DJ culture was nothing new for me.

We wanted to take the future into our own hands

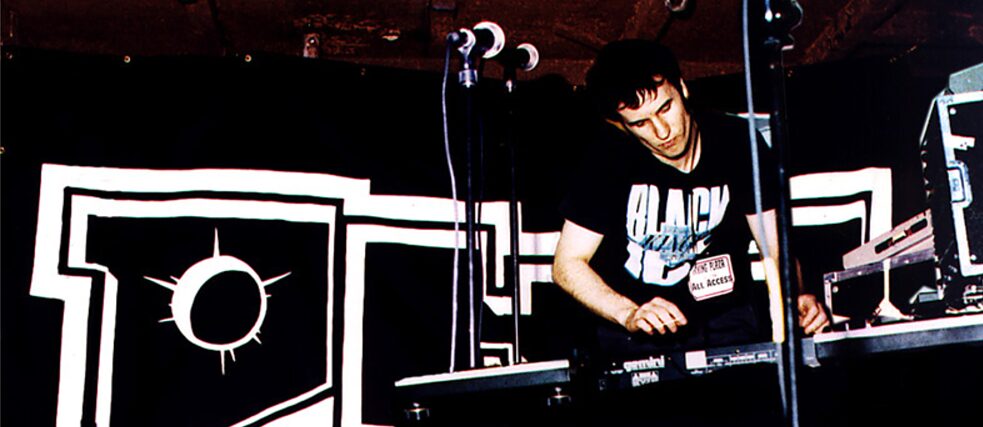

Atari Teenage Riot (1999)

| © Steve Gullick

What was your perception of the rave scene in Berlin back then?

Atari Teenage Riot (1999)

| © Steve Gullick

What was your perception of the rave scene in Berlin back then? There was no question at all that it was going to be big, not because it was somehow hyped, but because it was also the solution to a lot of problems in the music industry. That's really something that’s often forgotten. Rock music, which was associated with the traditional music industry, with the structure that it had, was very expensive and actually no longer with the times. It then became clear that we could work much faster and cheaper, and even drum up more energy in the process. It happened relatively quickly that a worldwide network formed. If you think about it, we’re talking about five, maximum six years until it was normal for raves to have 20,000 or 30,000 people. That was starting from a scene that began with 150 people. There was of course no Internet yet. The new sounds had to spread first. And that almost happened on its own. On top of that there was also this completely different consciousness that separated me and most people my age from the previous generation. We wanted to take the future into our own hands, whereas before it was always like: “Nihilism! Destruction! And so on.” These kinds of topics have always fascinated me – even later again, when I felt techno to be a dead end – but ultimately it was clear that we can program the future for ourselves. We just have to do it and find our own way.

“Where are they all coming from?”

You’ve been to illegal raves yourself. Can you describe a bit where those were and what such an evening looked like?It mostly spread via the typical things like flyers. But then there were also these answering machines. You called the phone number and then you found out where the location was. Then it was really easy: you set up the sound system and off you went. If you were there as a DJ or co-hosted it, it was always a risk because you hardly got any feedback initially. There was no pre-sale, so you could only roughly estimate beforehand how many people would come. Let’s say you had 1,000 people – I’m talking about the first ones now – then you think, “Where are they all coming from?” And then you want to repeat the same thing three weeks later. Then suddenly there are only 200 people and you ask yourself, “Why is it so different now?” But that was also quite interesting, because there was a lot of risk associated with it, and you had the feeling that you always had to come up with something new and look for locations. You always needed new ideas, for example how the flyers looked, how the idea came across and whether it was perceived as being exciting. It was really like an adventure. You just jumped into something where you didn’t know what to expect.

You were very critical of the West Berlin scene. What didn’t you like about it?

The people in East Berlin, and maybe this is also true for East Germany in a certain

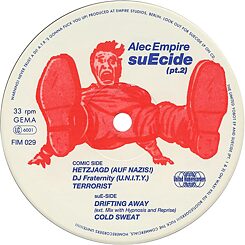

Alec Empire "SuEcide / Hetzjagd auf Nazis"

| © United Homerecorders

sense, had an extreme urge for freedom. It sounds like a cliché, but it was true. If the Wall hadn’t fallen at that point, things wouldn’t have gone off so explosively in the West either, because it was about more than that for the people from the East. They were all extremely disappointed and frustrated with everything that had to do with socialism. That’s really a very important thing that tends to fall by the wayside. Some of the people from the East went into the techno scene. But others went directly into the radical right-wing scene out of anger. That even goes for people who had been punks in the GDR in the 80s. That was a very difficult time. That’s why with Atari Teenage Riot we came up with songs like “Hetzjagd auf Nazis” (Hounding down Nazis) with a political stance that we felt was very important. I just didn’t like this “peace love and harmony” thing. “We’re throwing a party here so quiet down now!” was not the right proclamation for us out of this new world which had so much to do with insecurity, corruption of politics and also big corporations. Right away in 1990, after the fall of the Wall, an important mood emerged. But I didn’t really criticize the West Berlin scene, but rather those who didn’t understand the political context or that didn’t care about it. It’s one thing to work on the future, to let a techno culture develop and try out new ideas. But it’s another thing to completely close your eyes to the reality that goes on outside these spaces.

Alec Empire "SuEcide / Hetzjagd auf Nazis"

| © United Homerecorders

sense, had an extreme urge for freedom. It sounds like a cliché, but it was true. If the Wall hadn’t fallen at that point, things wouldn’t have gone off so explosively in the West either, because it was about more than that for the people from the East. They were all extremely disappointed and frustrated with everything that had to do with socialism. That’s really a very important thing that tends to fall by the wayside. Some of the people from the East went into the techno scene. But others went directly into the radical right-wing scene out of anger. That even goes for people who had been punks in the GDR in the 80s. That was a very difficult time. That’s why with Atari Teenage Riot we came up with songs like “Hetzjagd auf Nazis” (Hounding down Nazis) with a political stance that we felt was very important. I just didn’t like this “peace love and harmony” thing. “We’re throwing a party here so quiet down now!” was not the right proclamation for us out of this new world which had so much to do with insecurity, corruption of politics and also big corporations. Right away in 1990, after the fall of the Wall, an important mood emerged. But I didn’t really criticize the West Berlin scene, but rather those who didn’t understand the political context or that didn’t care about it. It’s one thing to work on the future, to let a techno culture develop and try out new ideas. But it’s another thing to completely close your eyes to the reality that goes on outside these spaces.

I think the ideas behind the techno from that time itself still exist.

For us there was always a difference between something being “commercial” and commercialization. So if the music itself, or even a certain concept for a rave, a club, or a certain artwork was popular and then blew up and became well known, then it was totally fine by me. That didn’t automatically mean it was bad. What we rejected was trying to make compromises to reach an audience, which actually has nothing to do with the music and the scene. There was a very clear separation for us and that was commercialization at that time. For example, whether you want to edit a track down for the radio. I’m generally not against changing or adapting things, that’s always been a part of DJ culture. But there is a limit. You have to know for yourself where to draw it.

How do you see techno today?

In these videos of DJ sets on social media – there’s simply nothing left to feel of the euphoria, the enthusiasm and the energy of the early days. But that’s important for it! I think it’s tragic when you see people holding up their phones and trying to capture something that just isn’t really there. That’s how I see techno today. I think the ideas behind the techno from that time itself still exist. Those can also be strategies to move forward and find ways out of this dead end. But people have to recognize that, of course. So if everyone goes to the clubs and there’s music playing that doesn’t mean anything to them and doesn’t reflect any kind of zeitgeist, then it’s just not alive and not exciting. But I expect more of a renewal in electronic music than in hip hop or rock music, for example. Hopefully techno has a future, because it was actually the beginning of something that hasn’t finished yet.

Alec Empire

Alexander Wilke-Steinhof aka Alec Empire is a music producer, composer and DJ. He is the frontman of the group Atari Teenage Riot and founder of the labels Digital Hardcore Recordings and Eat Your Heart Out Records. He has been releasing music in a wide variety of electronic styles since 1991, including on “Mille Plateaux”, Achim Szepanski’s label that references the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. He has worked with a wide variety of artists, including Björk, Nine Inch Nails and Mogwai. Alec Empire lives in London and continues to perform today, including with Atari Teenage Riot.

Playlist Alec Empire

This playlist is the part of the tracks submitted by Alec Empire available on Spotify. It gives you a small overview of Digital Hardcore Recordings and his own work. Unfortunately, due to licensing reasons and lack of availability, some tracks had to be omitted. For the complete list please write to the editors.

Comments

Comment