Jeanette Ehlers’ work is being presented today in a cultural partnership with Scotland. Through her transnational creativity, the European politics of race and culture is being examined from England’s “Celtic fringe”, a place which has its own bitter and bloody colonial histories. I want to try and cook with local and seasonal ingredients—low foodmiles. That means starting with Scotland and saying something about how a Scottish connection might make a difference to the kinds of conversation we can have today about Jeanette’s amazing art.

It is necessary but too easy to just talk about the history of Scottish slave trading or the involvement of Scots as entrepreneurs and military labourers in the extended defence of Britain’s empire. That colonial wealth is manifested in the material structure of Scottish cities. The loot fills Scottish museums and universities. There are other layers of complexity to that story which can be acknowledged without taking anything away from how Scotland has suffered at the hands of the English. All those things need to be mentioned repeatedly.

But today I prefer to start somewhere else: with the figure of Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet. It’s well known now that he was somebody who several times turned down the option on traveling to Jamaica to work as a plantation overseer/bookkeeper. But that is not all we need to say about him. Burns’ found and articulated an “ecological” humanism. His pronounced moral sensibilities and his philosophical outlook have had other effects in the black Atlantic world. His poetry and outlook strongly influenced the fugitive African American slaves and abolitionists who came and spoke here, strengthened in their own belief that a man’s a man for a that.

Many more African American activists in the cause of antislavery arrived in Scotland with plans to make humble pilgrimages to Burns’ grave.

We know from the pioneering work of the historian George Shepperson that Frederick Douglass’ interest in Scotland preceded his antislavery lectures which commenced during the spring of 1846. Before that, the great anti-slavery orator had been exposed to romantic representations of Scotland and its peoples. He had come across those ideas and images while still enslaved. This was a long time before he purchased what would become his cherished personal copy of Burns’ Collected Works from a bookshop in Massachusetts.

Many more African American activists in the cause of antislavery arrived in Scotland with plans to make humble pilgrimages to Burns’ grave. They interviewed his surviving relatives and made clear their passion for his poetry. We need to know why they did and the answers we can discover, may have a bearing upon the meaning and the effect of Jeanette’s extraordinary pieces.

“I am here because you were there”, unfolds into I am, because I belong.

O wad some Power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!

Jeanette’s work celebrates resistance against the hypersimilarity or interchangeability specified by racism and the individualized, racialising experience of seeing oneself being seen. Those mechanisms deny the black any legitimate individual identity or authentic subjectivity. But her’s is far from the usual, anguished liberal complaint about thwarted access to sovereign individuality. Here, the black sees herself being seen and understands, as Fanon did, the revelatory, alienating force of that epiphany. Jeanette plays with the impact of that disturbing perception: the confusion and disorientation that follows from facing up to the fact that you are being misrecognized as a Negro . . . “den Sorte” the same sound the greeted Nella on her peregrinations around Copenhagen.

The beautifully-lit faces of The Gaze affirm relational being and intersubjectivity. “I am here because you were there”, unfolds into I am, because I belong. Both pieces make variation ordinary and unexceptional. There is nothing exotic about this order of difference. It is a quotidian reality. Black is a beautiful word. I & I has circular form and demands that we re-think the relationship of singularity to plurality in the context of a racially-ordered and hierarchical space. “I am a possible you”. The gaze transcends distance. We share common ancestors. Our organic connection is subject to the contingencies of weather and fortune. The sadness of being ripped away from land and home in such a way that we can never be at home again. Long ago, in his trope of the changing same the poet Amiri Baraka offered us a productive image with which to render the figuration of difference. It came to mind while watching Jeanette’s more recent piece in which an infinite, flowing connection between individual, white clad female bodies prompted questions not only of multiplicity but of solidarity.

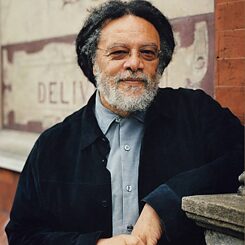

Paul Gilroy

Paul Gilroy, the founding director of the Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the Study of Racism & Racialisation, has been described as one of the foremost theorists of race and racism working and teaching in the world today. He is the author of several highly influential books There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack (1987), The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (1993), Against Race (2000), Postcolonial Melancholia (2005). Gilroy’s is a unique voice that speaks to the centrality and tenacity of racialized thought and representational practices in the modern world and has transformed thinking across disciplines. He has contributed to and shaped thinking on Afro-Modernity, aesthetic practices, diasporic poetics and practices, sound and image worlds. Gilroy won the Holberg Prize in 2019. Using philosophy, sociology, musicology, literature, history and critical theory, he has breathed new life into the humanist tradition, extending it to include scholarly and political discourses on race and anti-racist polemic.