October 2018

Babylon Berlin: Politics to the sound of the cocaine blues

While he’s best known as a master of the spy and thriller genre, John Le Carré’s early works are just as much detective stories, and his debut novel, Call for the Dead, is an intriguing murder mystery. When Samuel Fennan is found dead days after a routine secret service interview, George Smiley – scholar, gentleman, spy – has reason to suspect that the apparent suicide isn’t what it seems. His subsequent investigations – carried out independently from his sceptical employers at the “Circus” – point towards espionage from the new state of the German Democratic Republic and call up ghosts from Smiley’s own time as an agent in Germany before and during the war. Like the best of Le Carré’s work, Call for the Dead creates a satisfying puzzle, the solution to which is only gradually revealed, and it stages the drama of its characters’ lives against the backdrop of an uncaring and deadly European politics.

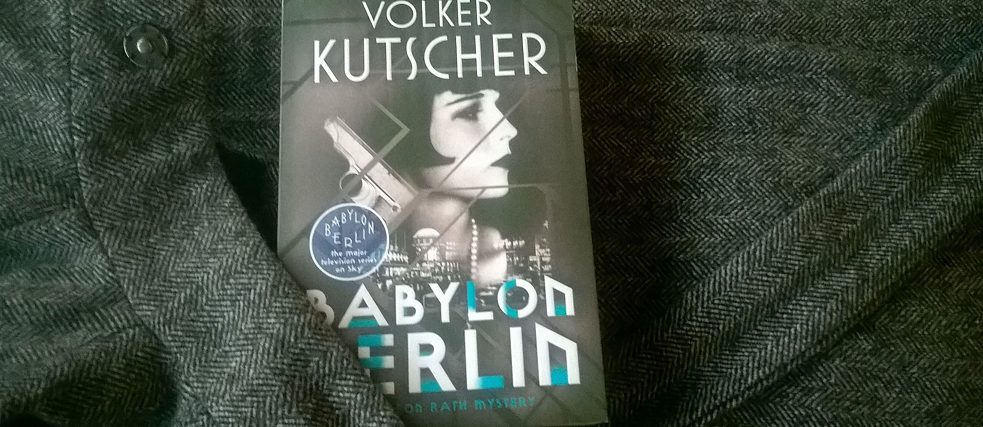

Volker Kutscher’s Babylon Berlin – the first novel in what’s planned as a nine-part series following Inspector Gereon Rath – similarly sets the detective story at its core against an urgent political backdrop. The year is 1928. The nightclubs of Berlin are dancing to the sound of the cocaine blues, while fascists, police and communists clash on the streets. (It isn’t hard to see why Sky picked the novel for a 2016 TV adaptation.) When a man he’d met fleetingly turns up in the police morgue, Gereon Rath too finds himself launching his own private investigation. The result? Intrigue, suspense, and fatal danger, accompanied by encounters with a Mafia boss, Russian exiles, and those “hobbyist soldiers”, the Brownshirts.

Kutscher’s mapping of the changing Berlin has clearly been carefully researched and the book is imbued with the atmosphere of the Weimar capital, with the city positioned as much as character as backdrop. Moreover, Neil Sellar’s crisp translation (hats off to Sellar for his smooth transposing of German’s often crucial switch between formal and informal address) keeps just enough of the taste of German without ever overdoing it.

While in both his drinking habits and the skeletons in his closet Rath is closer to detectives like John Rebus, his struggles to do the right thing within a system which seems increasingly compromised are reminiscent of a number of Le Carré’s books. Politics – and the resented, ruling Social Democrats – very much do influence policing (leading to a catastrophic confrontation between police and communist demonstrators near the start of the book) and, like Smiley, Rath has to deal with superiors who would rather cover up blunders than admit to treachery or hypocrisy within the force.

The series charts the rise of National Socialism through the eyes of Rath, and Kutscher resists the temptation to give his protagonists hindsight; the characters’ paranoia in the face of communists and their corresponding indulgence of the latter’s right-wing opponents offer a fascinating (if gut-wrenching) window onto a society rocked by social, financial and political instability.