June 2021

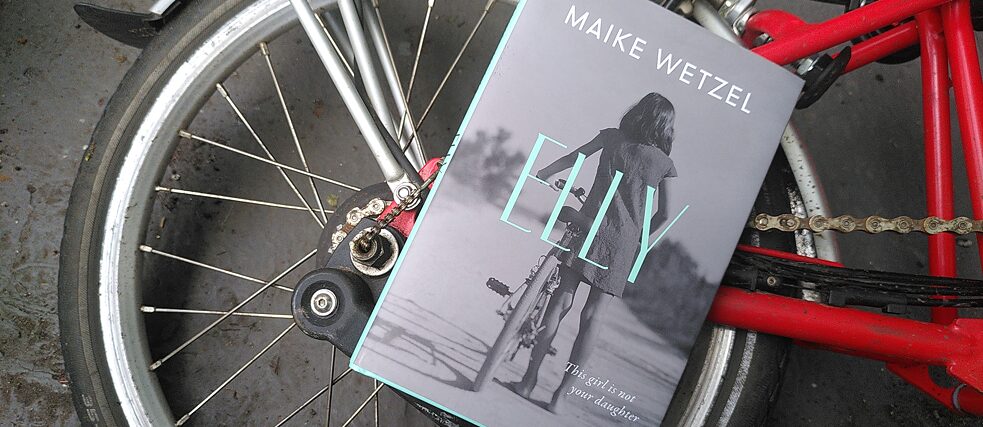

Maike Wetzel: Elly

If Ian McEwan’s The Child in Time intrigued you, we can recommend Maike Wetzel’s Elly.

We tend to expect novels to deal with the moment or the immediate aftermath of dramatic events. Crime books and thrillers ask the reader to follow the trail of a crime or a mystery when the scent is still fresh and emotions still raw. Ian McEwan’s The Child in Time (adapted into a film with Benedict Cumberbatch) subverts this, examining the continued sense of loss felt by a father two full years after his daughter has disappeared.

Maike Wetzel’s Elly (translated with clarity and deftness by Lyn Marven) similarly takes up its tale several years after the eleven-year-old Elly goes missing, and unpicks an obsessiveness prompted by the impossibility of closure. A slim novel, Elly avoids McEwan’s political philosophising to focus intently on the emotional lives of Elly’s mother, father and sister, who insistently cling to the belief that Elly is still alive.

The novel is full of dislocations and silences. The first section is narrated by a stranger – a young girl who shares a hospital room with Ines, Elly’s sister, and who Ines manipulates into pretending to be Elly on night-time escapades around the hospital. It’s a disquieting relationship, and the sequence sets the tone for the book, in which grief – and its denial – underpins everything. Later chapters are alternately related by the different members of the family, and while they outwardly remain united around the rallying cry that Elly is alive, their alienation from one another becomes increasingly clear.

The turning point of the novel comes with a phone call, four years after Elly’s disappearance. A 15-year-old girl has been found in Denmark who seems to match Elly’s description. Flights to Denmark are booked (the parents book separate flights, in case there is a crash). The girl returns home – and yet the unease, watchfulness and dislocations remain. “Our parents and I hold our breath so my sister can catch hers,” Ines remarks. “The new Elly”, as Ines calls her, doesn’t seem to catch her breath though, and as time goes on, more and more questions emerge – and yet are never spoken out loud.

Before Elly’s apparent re-appearance, Ines thinks: “My sister is dead. I hardly dare to think it, because I know my belief is enough to kill her. We’re all Elly has left. Our belief keeps her alive.” This superstition – the faith or desperate hope that by holding onto beliefs we can will them to be true – is the engine which propels everything forward in this assured and unsettling novel.

About the author

Annie Rutherford is an incorrigible bookworm and Jill of all (word-based) trades. She is the programme co-ordinator at StAnza (Scotland’s international poetry festival), a German-English literary translator, and runs Lighthouse Bookshop’s Women in Translation book group, among other things. She has been known to read while cycling (she does not recommend it), and can spot a misplaced apostrophe at a distance of fifty yards.Borrow the book in English translation digitally via the eLibrary.

Borrow the original German title digitally via the eLibrary.

Reserve your copy of the translated book in our library in London.

Find out more about the blog.