#DAOWO Sessions - Artworld Prototypes

How to Prototype the Artworld with Blockchain

By Régine Debatty

The DAOWO Sessions: Artworld Prototypes, a series of events that took place online over the past few weeks, explored “the possibilities for the future of the artworld with blockchain by investigating what can be learned from DAOs (Decentralised Autonomous Organisations) working with Others (-WO).” The theme of these sessions was remarkably relevant to the times we are living: a pandemic prompting us to work with each other differently, calls for a fairer society, art spaces looking for new strategies to remain relevant and the hysterical (or just baffled?) media interest for crypto art. The topic also inserts itself into a broader, much older context in which contemporary art follows market logics that don’t work for most artists.

DAOWO challenged artists to explore what would happen to their practice and communities if blockchain technology was not used only for financial transactions or as a marketing trick but deployed to reinvent the future of the art world. In the DAOWO prototypes, the accent is not so much on how art uses blockchain technology but on how blockchain principles can transform the art from behind the scene, by democratising the processes and design of its governance, by thinking in radical terms about how artists can become the conductors of their own working practices (rather than being dependent on the usual gatekeepers of the contemporary art industry.) As such, the prototypes also functioned as exercises in institutional critique.

The DAOWO Global Initiative asked groups of artists, curators and thinkers from Berlin, Hong Kong, Johannesburg and Minsk to design new prototypes to address key questions about the potential of blockchain to replace outmoded models, decentralise power structures and rewire the arts. The objective of these experiments is to test how a DAO would live in the art world and be used by its communities, members, users. Could they stimulate solidarity? Give rise to new forms of partnership? Incentivise new models of governance?

eeefff, Economic Orangery 2021. Screenshot from The DAOWO Sessions – Artworld Prototypes: DAO as Chimera (Minsk)

eeefff, Economic Orangery 2021. Screenshot from The DAOWO Sessions – Artworld Prototypes: DAO as Chimera (Minsk)

The most daring and creative DAO prototype was presented by artist and computer scientist Nicolay Spesivtsev together with artist and writer Dzina Zhuk from eeefff.

Their proposal takes the form of a live-action role play (LARP) firmly anchored in the political realities of a post-Soviet city like Minsk. The LARP, called Economic Orangery 2021, draws parallels between the kind of decentralised solidarity organisations that emerged in the small public courtyards of residential blocks found all over the city and their online equivalent: the specially constructed digital spaces that facilitate secure, non-censored communications. The artists added an extra layer of significance and playfulness by setting the game in a future when blockchain technology has become obsolete. This element of “science fiction of the present day” encourages players to consider the values of working with decentralised technologies both in the art world and in the context of the horizontal institutions that are emerging in the wake of the protests against the reelection of Lukashenko and the crumbling social structures of Belarus. The LARP is thus conceived as a co-dependency system where players’ decisions influence both the inner world structure of the game and their own perception of real life.

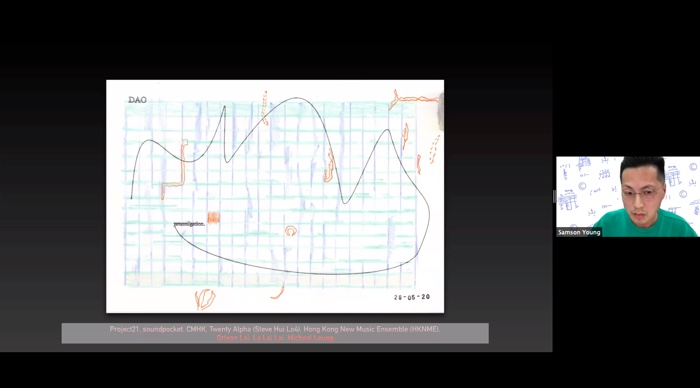

Screenshot from the DAOWO Sessions – Artworld Prototypes: Ensembl (Hong Kong)

Screenshot from the DAOWO Sessions – Artworld Prototypes: Ensembl (Hong Kong)

The Ensembl project from Hong Kong applied the dynamics of DAO to the interdisciplinary context of contemporary music-making. Ensembl is managed by Samson Young, artist, performer and artistic director of the experimental sound advocacy organization Contemporary Musiking; by writer, filmmaker and anthropologist Mao Mollona; and by Andrew Crowe and Ashley Lee Wong from MetaObjects.

The project ambitions to create an “Ethereum-Based Platform for Decentralised Organising of Artistic Production,” implementing a DAO that would fully reflect the inherently dynamic, collaborative and ever-changing nature of performances. Ensembl investigates questions of authorship and collective forms of artistic production, where performances, screenings and exhibitions are never fixed but constantly being shaped, (re)performed, (re)distributed. With each iteration of the work, new organisational and economic issues emerge.

Ensembl also reflects the many dimensions that an artistic practice can adopt over the course of a project, with artists successively finding themselves in the role of grant writers, artists, collaborators, managers, researchers, etc. Each role implies forms of labours that tend to be overlooked, if not invisible. Instead of thinking in terms of fixed roles, the project values action types and the outcomes of interactions.

Ensembl allows art-making to express itself as a process rather than a finished work.

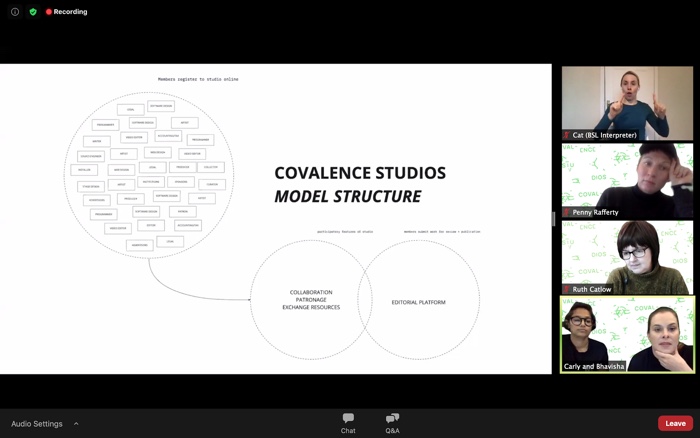

Screenshot from the DAOWO Sessions – Artworld Prototypes: Covalence Studios (Johannesburg) Zoom presentation

Screenshot from the DAOWO Sessions – Artworld Prototypes: Covalence Studios (Johannesburg) Zoom presentation

The Covalence Studios project, piloted by curator and researcher Bhavisha Panchia, artist Chad Cordeiro and artist, curator and researcher Carly Whitaker, used the idea and framework of the DAOs to consider the most flexible way to formulate, streamline and incentivise collaboration and participation in the artistic community of Johannesburg.

Johannesburg, Panchia and Whitaker explained, is home to a community of international artists who are increasingly distrustful of a public sector associated with mismanagement of funding and corruption in the department of art and culture. As a consequence, artists now have to rely more than ever upon the gallery sector to sustain their practices. This privatisation of art funding has influenced the type of works that get produced and limited the scope for more experimental practices. DAOWO could provide artists with more independence from public and private models of art management.

The DAO that the Johannesburg team envisioned is a shared artist studio space that would be co-owned and programmable. Conceived in conversation with other physical spaces such as Atlantic House in Cape Town and the Bag Factory Artist Studios, the studio would not only serve “communities that do not exist yet”, it would also free itself from the usual gatekeepers and silos of practice.

If you have to watch one video from the DAOWO session series, make it the above The Machine to Eat the Artworld, Francesca Gavin (whose show about fungi was extremely fun and instructive)’s interview with Ruth Catlow and Penny Rafferty, the curators who coordinated all the video sessions of the DAOWO Sessions – Artworld Prototypes.

Another conversation I would recommend is the Goethe-Institut's podcast episode in which Ruth Catlow, co-founder of Furtherfield, draws parallels between the early days of the web and blockchain. In the 1990s, she and other artists saw the web as a space where you could create, distribute, critique and circulate works, a place to collaborate and cooperate. Communications were direct and decentralised. From the early 2000s, the landscape saw the emergence of a movement of mass centralisation of the web orchestrated by monopolistic, profit-driven giants (Google, Amazon, Facebook, etc.)

The DAOWO initiative reminds us that decentralising movements and technologies are not going away and we need actors other than the ones belonging to the tech and finance sphere to scrutinise and operate them.

Another element I found particularly interesting about the DAOWO programme is that it was, as far as I know, the only initiative that seriously investigated that famous “world after” everyone talked about in the early days of the pandemic but seem to have forgotten about.