Series: German filmmaker in India (1)

A Procession of Masks

In this present series we examine a series of films produced by German authors in India. The series identifies these as being useful examples of a ‘visitor-film’. The first article explores different mechanisms by which to locate value and merit in the films produced by ‘outsiders’.

‘India was the land all men long to see, and having seen by so much as a glimpse, would not trade that glimpse for all the other sights of the world.’

In this quote by Twain, already a fallacy: the tendency, somehow, to imagine an entire country as a single, essential image – an artificial, violent assimilation. One may attribute this weakness to the rampant general hubris of much of the 19th century of course, but perhaps it is also important to note the consequences it has yielded in contemporary society. The reduction of an entire ‘nation’ – which as the various thought movements of the last two centuries reveal, is a concept, and therefore, rather complex – into an essential image is perhaps the underlying cause of a majority of the most apocalyptic events of the 21st century: the Twin Tower attacks, the ensuing wars, trade sanctions, the superhero film, the consolidation of tourism as an industry, international sporting competitions, and the resurgence of fascist movements across political spectrums. It may be simplistic to suggest that these exist as clear corollaries of each other, but it seems a lazy essentialism; a distillation of the most obvious, often cosmetic ‘truths’ about a land and then their subsequent proliferation is undeniable.

The equivalence here is important, too, for often enough, it is simple enough to denigrate the films produced by ‘foreign’, visitor-filmmakers as being inherently false or problematic. The contention of this thesis is that the fundamental tissue of the gaze reeks of infection, of prejudice, of a central limitation: the inability to see things for what they are.

In his story for The Guardian (‘How To Sell a Nation: The Booming Business of Nation Branding’, November 2017), Samanth Subramanian chronicles the professional adventures of Natasha and Alexander Grand, the chief strategists for INSTID, a branding management company whose clients are almost exclusively actual, physical destinations (cities, districts, countries). Through the article, Subramanian arrives at a fascinating conclusion that should have widespread repercussions in contemporary discourse: the branding agency does not merely help their clients promote who they are, but instead, help them identify who they are in the first place. The method employed by the duo to arrive at this clarity entails months of residence within the client-nation, a duration which necessarily entails a series of interviews, access to local literature, archives and documentation and an active exchange with the chief stakeholders of local society (businessmen, bureaucrats, the students). It is not difficult to locate parallels between this process and the one adopted by various visitor-filmmakers across ages. If the visitor-film fosters in its audiences habits of thought or meditation, it is possible that it begins to yield a similar set of results as those of the process employed by INSTID – in that, it helps its local audiences learn, first of all, about themselves.

In this regard, the influence of Germany looms large over film culture as it stands in India. An entire conclave of individuals – filmmakers, film exhibitors, film society activists – underwent an initiation within the studios (or on the streets) of erstwhile Berlin before they returned to India to forge complete, rather consequential careers. This includes K.S. Hirlekar, who trained in pottery in the Weimar Republic, but returned to India in the early 1920s to institute a tradition of the touring cinema. There is also Mohan Bhavnani, one of the first individuals to occupy the role of the Chief Producer at Films Division (his tenure – contentious – lasted from 1948 to 1955), and who trained as a filmmaker at the UFA Studios in Berlin. More pertinent examples abound: Devika Rani and Himanshu Rai, who were educated at the UFA and one may assume, conceived Bombay Talkies while there.

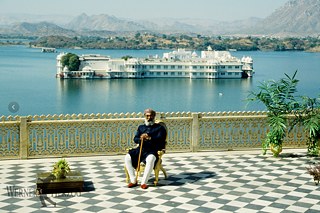

In the case of the most useful visitor-films, both the authority of the anthropologist and the listlessness of the tourist manifest simultaneously within a single title: think of Black Narcissus (1949), The River (1951) or Phantom of India (1967). Think also of Letter from Siberia (1957), where the author, Chris Marker contemplates – through reflection and then mockery – these tendencies of the visitor-film. This paradox is central also to the remaining titles we have chosen for the series: Franz Osten’s Shiraz (1928) and a set of short documentaries that constitute the filmography of Paul Zils. These are films whose chief protagonists can routinely seem like grotesque distortions (the subtitle of Jag Mandir is instructive: ‘The Eccentric Private Theatre of the Maharaja of Udaipur’) – figures who uncannily resemble a familiar ‘reality’ but still feel unfamiliar. And yet, as these films draw to a close, it is not difficult to diagnose the utmost sympathy, reverence and humility with which these characters are considered by their respective observers. One may conclude that this present series, ‘A Procession of Masks’, is a study of the rather distinct strategies adopted by the three filmmakers to arrive at this peculiar but astounding result.

In this present series, entitled, ‘A Procession of Masks’, writers from Lightcube, a film collective based out of New Delhi, examine a series of films produced by German authors in India. The series identifies these as being useful examples of a ‘visitor-film’ that perceives the subject of its study through a system of dignity, empathy and curiosity. The four articles contained in the series explore different mechanisms by which to locate value and merit in the films produced by ‘outsiders’ – as also, to look for new ways in which to talk of these titles. The series includes discussions of three primary examples: Werner Herzog’s Jag Mandir (1991), Franz Osten’s Shiraz (1928) and the films of Paul Zils.