Games: Drivers of Social & Political Change

Players are Drivers; Games are Vehicles

The common misconception is that games can compel changes, so let’s rethink the strategy!

By Pruthvi Das

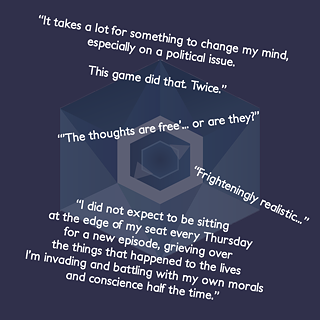

Have you ever played Orwell? Based in Hamburg, Osmotic Studios thought about exploring privacy concerns. Internet corporations are said to be the ‘Big Brother’ of our time; global surveillance, sales of user data, what have you? The game communicated what it’d be like if an authoritarian government had control, and not a business.

One would think this isn’t a good way to communicate privacy concerns, but it’s quite the opposite. Players described feelings of disgust, shock, horror and even paranoia and it’s all because the game’s message sank in their hearts. They never had to be told they were wrong for anything they did in-game.

If you’re trying to build games with the intent to change the player’s social or political views, then it’s important to make games that don’t overtly judge them for their actions or views. This is primarily due to the player already feeling judged by the consequences of their actions in-game. We know players project empathetic responses to certain decisions in-game. So, retrofitting extradiegetic consequences would only put them in a defensive stance, and make them believe that it was the designer’s intent to offend. But that’s what we expect them to think. The outcome would be fruitless; nobody would pay attention to the message.

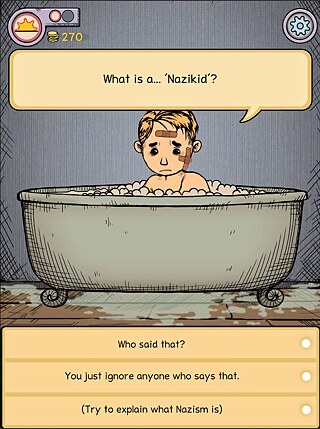

Ask yourself: how would you raise a product of this programme in a society with fresh wounds?

- ‘I wouldn’t. They can take all the punishment. They deserve it.’

- ‘I would protect them as if they were my own.’

The result? Players expressed positive emotions for the child. It succeeded in raising awareness about racial prejudice; often found in some contemporary societies towards Germans.

In retrospect, subtlety was indeed an issue to tackle. But that’s one part of the puzzle. The other is fairness.

It’s important to hold centrist ideals to provide the best (and worst) cases from both sides."

- The player won’t have control over what they do, and are forced to crawl through the preachy experience. We see this a lot.

- The player won’t feel as if their views are represented fairly and would no longer listen.

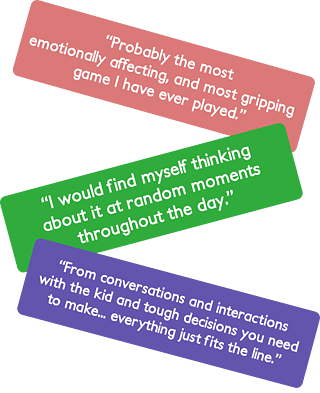

In fact, games are meant to take you away from reality. Jury’s out on whether it needs to be fun (but that’s another subject entirely), but games like That Dragon, Cancer and My Child Lebensborn indicate that they don’t have to be fun, just engaging. But in the context of games about change, relatability is everything. It’s what got the industry so many faithful followers. So, accuracy should be directed towards the representation of issues and not the realism of the setting itself.

Conclusion

It’s because social and political reforms are long-term deals; games simply act as tools to plant the seeds of change. We must start small and slow, and that begins with games being implicit about the player’s choices. The opposite isn’t as ideal as reprimanding someone’s actions heavily forces them to adopt new changes that are potentially polarising to them.For instance, semantics around gender tend to be miscommunicated, whether intentional or not; those at fault — the ones who choose badly, so to speak — are frowned upon, pushing them to be defensive. We can’t expect them to understand if they witness hostility and not reason. We do need to be clear about our judgments sometimes, but as means of actual persuasion, easing up on them is better. It’s why cancel culture has been so divisive.

Accepting an ideal comes from our own volition, provided that there’s an incentive. All it takes is a portion of empathy and time for the audience. We may not necessarily see change, or compel people to, but that’s not what impact is about anyway. It’s about creating food for thoughts. What drives those thoughts into fruition are the players themselves. We need to be the passenger and let them take the wheel.